On February 1, 2023, the UK’s HM Treasury (HMT) published a long-awaited consultation and call for evidence (Consultation) containing far-reaching proposals for anyone offering or thinking about offering cryptoassets within the UK or to customers in the UK. HMT is proposing to bring cryptoasset activities within the perimeter of the existing financial service regulatory regime in the UK under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), to the extent they are not already covered by other existing or proposed regimes (eg for stablecoins).

It has long been our view that the UK’s approach to regulating cryptoassets has been piecemeal, unsynchronised and could have contributed to potential consumer harm by driving firms overseas. The Government publicly shouts about putting the UK at the front and centre of the cryptoverse, yet we are falling behind. The UK regulators enforce the strictest cryptoasset service provider registration regime in the world and while some would say this has prevented a fallout from occurring on our shores, others would say this has hampered innovation.

Furthermore, many think the UK has uncharacteristically sat on the fence. This could be because the UK authorities foresaw and were keen to enable and promote the innovation that we see evolving in this space. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt.

The Consultation is arguably just another piece of the puzzle, rather than the clear, detailed rules the industry is waiting for.

So has the Consultation put the UK at the forefront of the cryptoverse? The jury is still out on that one. The Consultation is arguably just another piece of the puzzle, rather than the clear, detailed rules the industry is waiting for. The Consultation does, however, emphasize the vast amount of work going on in the UK to promote the crypto and Web3.0 industries. It finally lays out the roadmap and direction of travel for where the UK is going, which will bring some certainty and is therefore welcome.

Nevertheless, a lot of the detail is omitted and left for future consultations by HMT and the FCA. For example, what – if any – exemptions will be available to the cryptoasset activities such as the overseas persons exemption or the exemptions relating to “arranging” activities. And the elephant in the room that nobody is brave enough to tackle – what is the difference between a cryptoasset that looks and smells like a regulated security, but isn’t? (Or is it?).

And why should existing regulated firms need to vary their permissions just because they issue securities using distributed ledger technology (DLT) or other technology that supports the recording or storage of data – such as Cloud, a spreadsheet, a database and ledger, all those things used in financial markets today. This is the crux of the issue. Nobody has solved it or offered any clear guidance on it to date.

So we have the foundation of a roadmap. We have a good and clear direction of travel. But again the devil will be in the detail and the debates around cryptoasset regulation will continue at least until we see that. Time is not in our favour. The industry is moving apace. And it’s moving outside the UK.

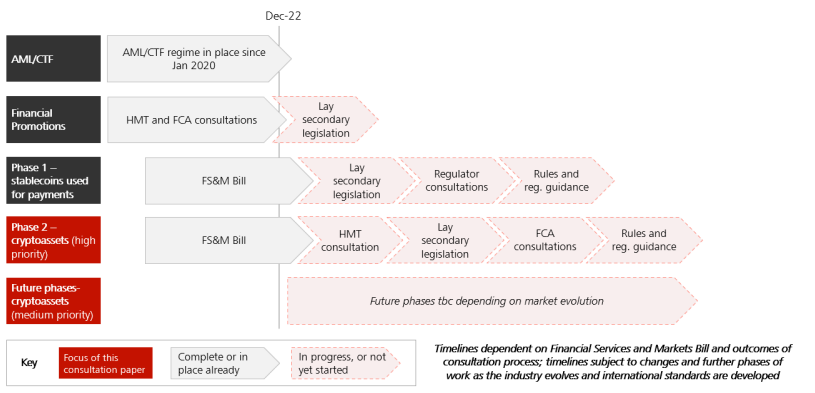

Phased approach

The UK will continue its phased approach to the regulation of cryptoassets as the crypto industry evolves. The Consultation constitutes the proposals for the second phase (Phase 2) in the development of the Government’s approach to regulating cryptoassets. The first phase of regulation has been legislating for the regulation of so-called “digital settlement assets” (the target of this regime being fiat-backed stablecoins used as payments) via the Financial Services and Markets Bill 2022-23 (see briefing).

In contrast to the EU – which has created a pilot regime for financial market infrastructure based on DLT (see briefings here and here) and the European Parliament approval on April 20, 2023 of the Markets in Cryptoassets Regulation (MiCA) (see briefing) – the UK’s approach to the cryptoassets sector has been piecemeal and sluggish. The UK intends to introduce a Financial Market Infrastructure Sandbox, and further details of this were set out in primary legislation discussed further below.

The Consultation at least sets out a clear, general direction of travel for the future regulation of cryptoassets in the UK, but a lot of the important detail will be in the secondary legislation HMT will lay in due course and then in the FCA’s proposed rules. There is also a question on how much detail the first set of legislative requirements can cover given the breadth of what is required. It would not be surprising if refinements and additions to the secondary legislation will continue for some time.

We are realistically looking at late 2024/2025 before the new regime arising from the Consultation would apply. Overall, the Consultation is a big deal but leaves a lot to the imagination. If the UK gets the entire package right, and does it quickly, it could make up ground lost to other jurisdictions and get back on track with the Government’s ambition of making the UK a crypto hub for the world. It would also be a powerful way of showing the world how to set the gold standard for managing market integrity and customer protection, as has been the case with other areas of financial services regulation.

Crypto regulation in the UK

Registration requirement for cryptoasset service providers

Firms providing cryptoasset services in the UK have to be registered with the FCA and comply with the anti-money-laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist-financing (CTF) requirements under the Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds (Information on the Payer) Regulations 2017 (MLRs). The rationale for this was clear, but the execution left a lot to be desired (or perhaps did not, depending on your view!). There are numerous strange outcomes with the current legislation, in particular:

- The MLRs have always contained a registration regime, but it has morphed into and/or been treated as a full authorization regime. The FCA’s approach to approving applications is akin to full authorizations, being among the, if not the most, stringent in the world. The UK has introduced the change in control regime to the MLRs, something else borrowed from the main regulatory regime in FSMA, begging the question as to whether using the framework of FSMA would have been the best model from the outset to provide realistic expectations.

We are conscious the UK had to implement the EU’s Fifth AML Directive in the midst of Brexit and EU Withdrawal Acts so parliamentary time and attention may not have allowed this. - The scope of the “arranging” permission is another misnomer. The wording is virtually identical to the wording in Article 25 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities) Order 2001/544 (RAO), but carries across none of the other features of the FSMA regime that give the full picture of the regulatory outcome intended by the draftsperson and legislators.

For example, none of the exclusions are copied over into the MLRs; exclusions which include introductions, arranging deals with or through [registered] persons and more. This is currently leading to the situation whereby many more firms are needing to get registered directly for what is in effect a white labelled product or a collaboration/partnership between a firm with knowledge, experience and procedures in the crypto industry (which is already registered) and traditional firms (which may also be regulated by the FCA too).

All the objectives and intended outcomes of the MLRs are met in this scenario (if not duplicated already). It is unclear to us why those exemptions have not been copied across, or why greater clarity on what “arranging” activities were actually intended to be captured has not been provided.

Any attempt to reverse engineer the cryptoasset regulatory regime into FSMA needs to carefully consider overlaps and prevent conflict with the MLRs.

Extension of the financial promotion regime to qualifying cryptoassets

In January 2022, the Government published its response to a July 2020 consultation on expanding its financial promotion regime to include certain “qualifying cryptoassets” as controlled investment (see briefing). Again, the financial promotion regime is baked into the framework of FSMA as the bedrock of the UK’s financial services regulatory perimeter regime.

We and industry have long advocated that the proposal would have amounted to an effective ban on crypto advertising in the UK since registered cryptoasset services providers could not even make their own financial promotions because they are not authorised persons under Part 4A of FSMA and, with the FCA’s tightening up of the financial promotion approval process and new gateway (further details in this briefing), it was all but certain that no firms would be willing to approve a crypto promotion on behalf of another firm.

Thankfully, HMT has now confirmed this issue will be resolved. On the same day as it issued the Consultation, the Government issued a policy statement confirming that:

- it will introduce a new exemption to Section 21 of FSMA enabling cryptoasset exchange providers or custodian wallet providers registered with the FCA under Regulation 54(1A) of the MLRs to communicate their own promotions in relation to “qualifying cryptoassets”;

- registered cryptoasset businesses relying on this exemption will not be able to approve financial promotions or communicate their own financial promotions in relation to other controlled investments;

- the FCA will be given powers to enable it to make rules applying to financial promotions communicated with reliance on this exemption to ensure that firms are subject to the same financial promotion rules as authorized persons communicating equivalent promotions;

- the exemption will not apply to registered cryptoasset exchange providers or custodian wallet providers that are also authorized persons, as these cryptoasset businesses are already able to communicate their own financial promotions without the need for this exemption;

- the statutory instrument adding “qualifying cryptoassets” to the financial promotions regime was laid out in the draft version of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) (Amendment) Order 2023 published in April 2023; and

- the exemption is intended to be temporary and the Government will review its approach to the exemption alongside the future regulatory approach to cryptoassets.

The FCA has also consulted on proposed rules for cryptoasset promotions, such as risk warnings and consumer frictions (see briefing).

The FCA published its policy statement on financial promotions for cryptoassets on 8 June 2023. See briefing here.

*The statutory instrument adding “qualifying cryptoassets” to the financial promotions regime was the – Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) (Amendment) Order 2023 – was made on 7 June 2023 and will come into force on 7 October 2023.

Stablecoin (digital settlement asset) regulation

In April 2022, the Government confirmed its intention to bring stablecoins which are used as a means of payment within the existing regulatory regime for payment services and e-money (further details are available).

In July 2022, the Financial Services and Markets Bill 2022-23 (FSM Bill) was introduced into the UK Parliament and contained provisions that would:

- bring “digital settlement assets” (DSA) used for the settlement of payments into the regulatory perimeter for systemic payment systems and service providers (systemically important entities would fall within the remit of the Bank of England); and

- enable HMT to bring activities such as the issuance and custody of fiat-backed stablecoins into the regulatory perimeter via a statutory instrument (to come under the remit of the FCA).

The scope of this is expected to cover, at a minimum, GBP and other fiat-backed stablecoins issued in the UK. The Government confirms that further details on the Government’s approach to fiat-backed stablecoins will be set out in due course.

The Government has explained that the concept of a DSA could extend to cryptoassets other than fiat-backed stablecoins (eg if an unbacked cryptoasset was used for payments and became systemic in nature). The regulation/legislation in question would focus on the regulation of issuers, custodians and payment service providers for fiat-backed stablecoins and would not capture exchange or trading activities of stablecoins.

Regulating stablecoins under the framework established for e-money and payments is another sensible approach in principle – using the existing legislative framework to regulate the same risks and similar types of activity. However, the devil will again be in the detail. After all, what is the difference between e-money and an e-money token/stablecoin other than the technology underlying it?

It is important to challenge ourselves to consider what is really unique and what is merely an evolution of the technology on which our capital markets were built.

Lawyers may scream at this along the lines of “oh, it does not amount to ‘funds’” or “there’s no claim on the issuer” – but these are sometimes technical legal arguments. The activity and risks are broadly the same. It is important to really drill down into the features of DLT and similar technologies to challenge ourselves to consider what is really unique and what is merely an evolution of the technology on which our capital markets were built. It is unwise to conflate the two issues.

A natively issued non-fungible token (NFT) representing ownership of a piece of artwork that only exists in digital form is a new asset class. But that’s not to say it needs to be brought within the sphere of financial regulation. Traditional artists are not forced to produce disclosure documents to be signed off by financial regulators when offering their paintings or music for sale in galleries or streaming services where such paintings or music for sale are open and accessible to the public at large. However, auction houses, which may process large sums of money for high-value goods, were brought into the scope of the MLRs as the gatekeepers/intermediaries.

The same framework should largely apply to crypto if we are going to regulate it at all, which seems a foregone conclusion despite the arguments to the contrary.

Broader digital assets and DLT topics

HMT rightly reminds us of various other workstreams that are ongoing in the UK in relation to digital assets. The graphic below, taken from the Consultation, summarises this work.

Other cryptoassets

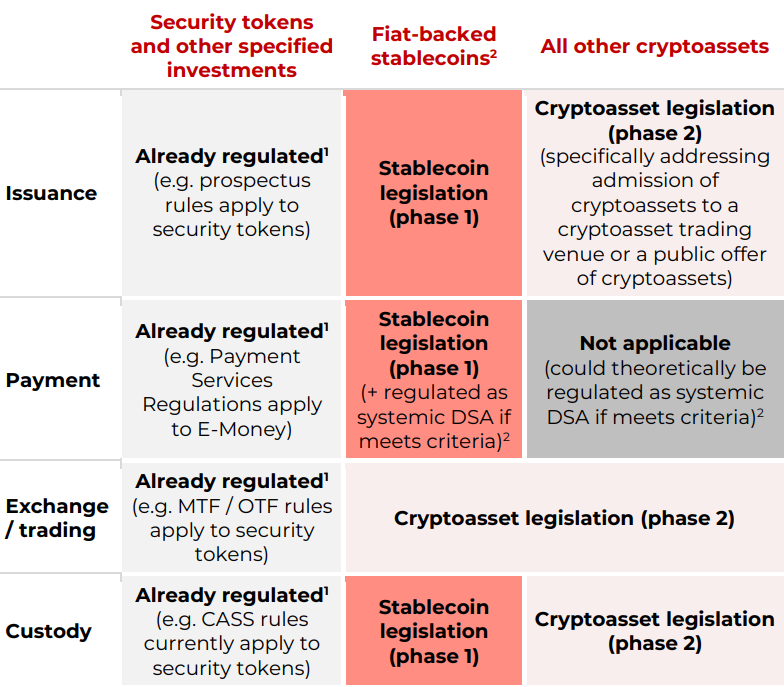

The UK’s proposed approach will introduce a regulated activities regime in relation to cryptoassets inspired by the pre-existing regulated activities regime in UK legislation under FSMA (covering activities such as issuance, intermediary activities, safeguarding and lending).

Under FSMA, HMT has secondary legislation powers to bring activities into the regulatory perimeter by specifying them in the RAO. It will also have powers under the FSM Bill to designate activities as part of a new Designated Activities Regime (DAR). The current version of the FSM Bill includes a provision to expand the list of “specified investments” in Part III of the RAO to include cryptoassets and to clarify that persons (natural or legal) carrying out certain activities involving cryptoassets “by way of business” would be performing regulated activities and therefore require authorisation under Part 4A of FSMA.

The Consultation explains that this would result in the FCA being given powers to write bespoke rules, as opposed to the existing rules automatically applying to cryptoassets.

“Any cryptographically secured digital representation of value or contractual rights that: (a) can be transferred, stored or traded electronically; and (b) that uses technology supporting the recording or storage of data (which may include distributed ledger technology).”

FSM Bill: Definition of a cryptoasset

This definition of cryptoassets is similar to that of cryptoassets contained in MiCA. The FSM Bill also contains provisions allowing the definition of “cryptoasset” to be updated by way of secondary legislation.

The Government confirms that it does not propose to expand the definition of “financial instrument” in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the RAO to include presently unregulated cryptoassets, but would introduce equivalent or similar safeguards where cryptoassets pose similar risks to financial instruments.

Under the proposed regime, the focus would be on financial services activities connected to the cryptoasset rather than the cryptoasset in question. Activities in scope would include:

- issuance activities;

- exchange activities;

- investment and risk management activities;

- lending, borrowing and leverage activities; and

- validation and governance activities.

The Consultation sets out design features for each regime, covering themes such as prudential requirements, data reporting, consumer protection, location policy and operational resilience.

The question of whether an NFT would come within scope of the UK regulatory regime would depend on the particular structure and characteristics of the NFT and the activities carried on in relation to the NFT. The Government also confirms that NFTs will not be in scope of the cryptoassets financial promotions regime.

In setting out its proposed approach to the regulation of cryptoassets activities, the Government cautions that:

- the wording of the activities is not meant to be interpreted as draft legislation/wording of regulated activities, but is meant to provide an illustration of the types of activities HMT intends to regulate (and when);

- the list of activities set out in the Consultation is not exhaustive and activities with a very similar nature, purpose and risk profile could be captured in the perimeter; some future activities (beyond Phase 2) may ultimately be left out of the regulatory perimeter in full or in part;

- some activities (such as custody) will be addressed in Phase 1 in relation to the work on fiat-backed stablecoins as payments and later in relation to work for other types of cryptoassets (Phase 2);

- there will be exemptions eg only firms/individuals undertaking cryptoasset activities by way of business would be regulated (this is particularly relevant for activities such as dealing in cryptoassets as principal, mining and validation).

- unless specific exceptions / exemptions apply

- Any systemic Digital Settlement Asset payment system or service provider would be subject to

regulation by the Bank of England and Payment Services Regulator (PSR)

The framework for regulation

We think these factors are key to HMT’s thinking and proposals. They already have the power to amend the RAO and the FSM Bill contains explicit powers. FSMA will then act as the framework for policing the perimeter of cryptoasset regulation in the UK, in the same way it does for most other (financial) regulated activities. FSMA will set out a criminal offence of offering cryptoasset activities in the UK unless authorized or exempt.

The financial promotion regime will apply. The regulatory supervisory and enforcement powers will flow down. The regulators will then call on existing (and well-tested) powers to make rules for specific sectors. There will be a bespoke regime for crypto, but FSMA provides the right framework in our view to regulate cryptoasset activities with a financial services dimension.

The key question nobody has really answered clearly yet is how much of this industry should be regulated by financial services regulators and how much should be left to private law and consumer protection laws generally. Where is the line between what is a cryptoasset and what is a “share” or an “instrument acknowledging indebtedness” or a “unit” in a fund? Can a “thing” be both? Does a firm need permissions for both if the activity is not different? There could be regulatory arbitrage if this line is not clearly drawn. And it’s not an easy one to draw.

Focussing on the token itself or the technology itself sometimes results in odd outcomes. Whatever the Government does, clearly delineating the perimeter of where the traditional financial world ends and the cryptoasset world begins (or acknowledging they overlap) remains a critical, foundational question.

To give an example. You can buy a Picasso at an auction house today; list it for sale next year in a frenzy of competing bidding interests during the auction to buy that prized Picasso; you might lend it to a gallery to put on display; you might take out a loan against it or borrow someone else’s asset in return for lending it; you might ask somebody else to look after it. Aside from the MLRs, financial services regulation does not apply to this activity today. It could, however, apply under the proposed regime if one conducted (substantially) the same activity in relation to an NFT trading on an NFT auction platform/exchange.

Is that where we want to be heading? Again, we fully appreciate the complexities of the legal, regulatory and moral implications of this debate and we are fully engaged in it. This is an oversimplification of hugely complex issues that the great and the good are working through on the world stage.

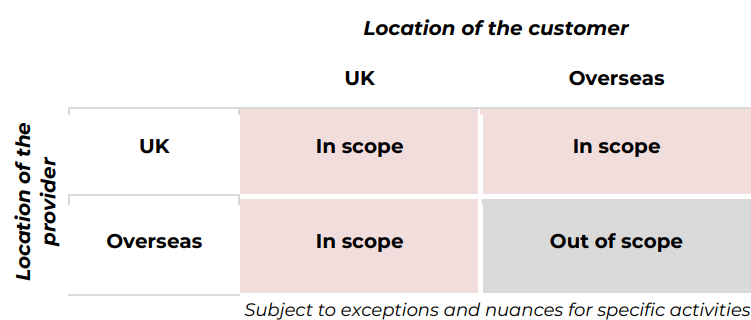

Geographic scope

The proposed regime would cover cryptoasset activities provided in or to the UK, and so would capture activities provided by UK firms to persons based in the UK or overseas (natural and legal), as well as those provided by overseas firms to UK persons (natural or legal), as noted in the graphic below.

The Government considers this to be necessary as UK consumers are able to access cryptoasset products and services provided by overseas companies. The Government has already acknowledged that there will be nuances to this approach.

For example, it foresees reverse solicitation being accommodated so the authorization regime would not cover instances where a UK customer accessed a particular cryptoasset service entirely at their own initiative. It states that this provision would need to be defined to prevent regulatory arbitrage. Hopefully, HMT will also consider whether other existing exemptions, like the overseas persons exemption, will be applied to cryptoasset activity in order to enable wholesale market activities. This needs to fit in with HMT’s wider review of this exemption, but that may take longer.

There is no final say yet in relation to whether firms carrying out these activities would be required to have a physical presence in the UK in order to obtain authorization, and the Consultation states that this is for the FCA to determine, but that any decision would be informed by the existing framework, which looks at the nature and scale of a firm’s activities and risks of harms (ie risk of retail, client asset and wholesale harm). The Consultation also states that firms operating cryptoasset trading venues would be likely to require subsidiarization in the UK.

Under the proposed regime, equivalence would be possible where firms authorised in third countries can provide services in the UK without needing a UK presence, provided they are subject to equivalent standards and there are suitable cooperation mechanisms. The Government states that it would be looking to pursue these equivalence determinations as soon as possible. We remain sceptical on the speed of this given the time it might take to achieve global consistency.

Algorithmic stablecoins

The Government’s regulatory approach has been somewhat informed by high-profile bankruptcies and collapses of various cryptoexchanges, lenders and issuers and the issues these have generated in relation to managing conflicts of interest and adequately safeguarding assets. However, much of the detail in this regard will be set out in the pending secondary legislation and FCA rules.

The Government states that firms would be expected to follow rules covering all activities and not just those relevant for operating a trading venue. A major cryptoasset exchange would, therefore, be required to comply with rules concerning the issuance and disclosure for assets that they admit for trading; the rules relating to the operation of a trading venue; and certain surveillance and reporting requirements to detect and prevent market abuse. It states that these entities may also be required to comply with rules for market intermediaries, depending on the sorts of activities they undertake, and comply with a set of cryptoasset custody rules for cryptoassets which they safeguard or safeguard and administer

Algorithmic stablecoins aim to maintain a stable price largely, or in some part, through an algorithm that facilitates a change in supply and demand between the coin and one or more cryptoassets that support it. In May 2022, the cryptoassets sector was rocked by the collapse of TerraUSD token, which relied on a linked cryptoasset called “Luna”. The Consultation notes that algorithmic stablecoins are typically undercollateralised.

Under the proposed UK regime, algorithmic stablecoins would not qualify as a stablecoin under the regime for fiat-backed stablecoins, but would be subject to the same requirements as for unbacked cryptoassets. The Government argues that cryptoasset financial promotions rules, which will require (amongst other proposals) in-scope promotions to be clear, fair and not misleading should reduce the risk of firms marketing algorithmic stablecoins as “stable”, “payments instruments” or very similar terms

Issuances and disclosures

The Government is proposing to establish an issuance and disclosures regime for cryptoassets based on the reform of the UK prospectus regime (the Public Offer and Admissions to Trading Regime), as confirmed in March 2022 and in the December 2022 Edinburgh Reforms (for more information see briefings here and here).

The proposed reforms to the prospectus regime consist of: a general prohibition on public offerings of securities, subject to certain exemptions such as, where the securities are admitted to trading on a UK Regulated Market, where the securities are admitted to trading on a multilateral trading facility (MTF) operating primary markets, and securities offered via a “public offer platform” (a new bespoke permission for platforms for public offers of unlisted securities, such as crowdfunding platforms).

There are exemptions depending on the type or scope of public offer, including offers below a de minimis monetary threshold, offers made only to “qualified investors” and offers made to fewer than 150 persons. This regime would be adapted to the specific attributes of cryptoassets.

In relation to cryptoassets, the Government identifies two regulatory “trigger points”: admitting (or seeking the admission of) a cryptoasset to a cryptoasset trading venue; and making a public offer of cryptoassets (including Initial Coin Offerings). In relation to admission of cryptoassets to a UK cryptoasset trading venue, an amended MTF model from the intended reform of the UK prospectus regime is proposed to be applied. This would involve principles in the FCA rulebook for admission and disclosure requirements that cryptoasset trading venues would be responsible for administering.

The trading venue would be required to take on the responsibilities of the issuer if they wish to admit the asset to trading where there is no issuer.

Cryptoasset trading venues would be responsible for preparing more detailed content requirements for admission and disclosure documents, as well as performing due diligence on the entity admitting the cryptoasset. The trading venue would be required to take on the responsibilities of the issuer if they wish to admit the asset to trading where there is no issuer. The Consultation states that the venue would have a choice as to whether the admission and disclosure document itself has to comply with financial promotions rules, or whether it has to be accompanied by a separate document for this purpose.

Under the proposed framework, the intended Public Offers and Admissions to Trading Regime would capture public offers of cryptoassets meeting the definition of a security offering and considered a Security Token Offering. For non-security token offerings, the Government is proposing to use its new powers under the DAR to prohibit such offerings unless they are conducted via a regulated platform.

A regulatory framework based on existing RAO activities of regulated trading venues (including the operation of an MTF) is proposed that would subject persons carrying out these activities to prudential rules and a number of other requirements, including consumer protection, operational resilience, and data reporting.

Intermediation activities

The Government refers to concerns by the Financial Stability Board raised in relation to risks that can emerge from these activities, including those arising from conflicts of interest and credit and liquidity risk. It proposes that requirements applying to similar regulated activities – such as “arranging deals in investments” and “making arrangements with a view to transactions in investments” set out in Article 25 of the RAO – would be used and adapted for cryptoasset market intermediation activities. They would include prudential, conduct, operational resilience and reporting requirements and would require authorisation. Applications would need to include items such as details of operations, services and business plans.

The Consultation notes that the digital nature of cryptoassets means that cryptoasset custody differs in fundamental ways from traditional financial custody arrangements. A proposed regulatory regime would apply and adapt existing frameworks for traditional custodians under Article 40 of the RAO and the FCA’s Client Assets Sourcebook for cryptoasset custody activities, with some amendments to take account of cryptoasset features.

The so-called regime for the safeguarding, or safeguarding and administration (or arranging the safeguarding or safeguarding and administration) of a cryptoasset other than a fiat-backed stablecoin would be broader than the current Article 40 activity, which only applies when firms are both safeguarding and administering.

We suspect “replaced” will not amount to a completely new regime, but more clarifications and adjustments to the existing framework.

The Government expects the same custody requirements will be adopted for all types of cryptoassets as they come into regulation. For cryptoassets that already meet the definition of a specified investment (security tokens), the existing regulatory framework that currently applies will be replaced by the new custody regime. We suspect “replaced” will not amount to a completely new regime, but more clarifications and adjustments to the existing framework. The Government will also consider future work done in this area.

Existing custody provisions in the Client Assets Sourcebook (CASS) are to serve as a basis to design bespoke custody requirements for cryptoassets. Key requirements would include: adequate arrangements to safeguard investors’ rights to their cryptoassets (eg restrict commingling of investors’ assets and the firm’s own assets); adequate organisational arrangements to minimise risk of loss or diminution of investors’ custody assets; accurate books and records of investors’ custody assets holdings; and adequate controls and governance over the safeguarding arrangements and operational processes in place.

Market abuse requirements

Like MiCA, the UK is considering introducing a market abuse regime in relation to cryptoassets. The Government discusses the challenges of adapting existing market abuse regulation to crytpoassets. These include the fact there is less likely to be “a single identifiable issuer” to place issuer obligations on in respect of controlling inside information (as opposed to traditional securities markets where the Government argues that the main holder and creator of inside information is often the issuer).

Inside information, it is argued, would be more likely to be held/created by entities other than the issuer (eg miners, validators and oracles), making manipulation harder to detect. HMT contrasts what it deems to be the globalised, fragmented, and borderless nature of cryptoasset markets with localised equity and fixed income markets, where it argues that there are clear “main” markets where the majority of trading is concentrated.

The Government is proposing a cryptoassets market abuse regime based on elements of the Market Abuse Regime for financial instruments. The offences against market abuse would apply to all persons committing market abuse on a cryptoasset that is to be admitted to trading on a UK trading venue, irrespective of where the person is based/ where the trading takes place. Trading venues would have primary responsibility for preventing, detecting and disrupting market abuse. The scope of the market abuse regime would be cryptoassets that are requested to be admitted to trading on a cryptoasset trading venue (regardless of where the trading activity takes place). The regime would require all regulated firms carrying out cryptoasset activities to manage inside information.

Regulation of lending platforms

It is noted that businesses in these areas offer services such as: collateralised lending; peer-to-peer lending; securities lending (eg exchanges providing margin loans); investment management; and unsecured credit products. Recent high-profile cases are clearly on the mind of the Government as it argues that credit risk has been a significant factor behind cryptoasset market turbulence. It argues that platforms carrying out lending and borrowing activities need to have sufficient resources to manage counterparty credit risk and meet all liabilities as they fall due.

It is proposing the creation of a newly defined regulated activity: “operating a cryptoasset lending platform”. This would include facilitating collateralised and uncollateralised borrowing of cryptoassets or borrowing of fiat currency with collateral provided in cryptoasset form. Requirements for the lending platforms would include: adequate risk warnings for consumers lending to the said platform (eg that the consumer could lose all their money and clarity on the lack of Financial Services Compensation Scheme protection); adequate financial resources; and clear contractual terms on ownership and, if applicable, ringfencing of retail funds in case of insolvency.

It is also proposed that a regime for cryptoasset lending platforms should consider the need for firms to have effective risk management of collateral, including appropriate collateral valuation; contingency plans for the failure of participants’ largest market counterparties; and the management of collateral following default.

Calls for evidence

The Government is considering a range of approaches in this area, noting unique and complex challenges in relation to DeFI, as well as ongoing plans to regulate DeFI at the international level. The Consultation characterises DeFi product chains as involving a long list of actors, from limited companies and coders creating or editing protocols and code, to Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and governance token holders.

One option for regulation that is discussed is to define a set of DeFi-specific activities (such as “establishing or operating a protocol”) as regulated activities under the RAO (or DAR). In-scope persons would then require authorisation, with a bespoke FCA regime around these regulated activities.

Views are sought on whether: there is a case for making cryptoasset investment advice and cryptoasset portfolio management each a regulated activity; there is merit in regulating mining and validation activities in the UK; staking (excluding “layer 1 staking”) should be considered alongside cryptoasset lending as an activity to be regulated in Phase 2.

Entities governed by MLRs

The Government confirms that the introduction of an authorisation regime under FSMA for persons who are carrying out certain activities involving cryptoassets means that crypto firms already registered under the MLRs and carrying out those activities would be required to also seek authorisation under the new FSMA-based regime. A proportionate and timely authorisation process with an aim for complete and accurate applications is proposed. A separate registration under the MLRs would not be required for new crypto firms not yet registered under the MLRs.

Getting this transition right will be key to avoiding market disruption and further delay. There would seem to be a case for a lighter-touch regime or fast-pass for firms who are already FSMA authorised and registered under the MLRs. It is not yet entirely clear what else the FCA could require of such firms or what extra risks such firms present that are not already supervised.

The transition of firms regulated under the MLRs would ideally be pragmatic and proportionate too, not least because the FCA has treated the applications like a full authorisation for the most part, noting some key aspects are not identical — such as the senior managers regime, client assets, and prudential requirements (all of which add significant time to and effort to any authorization process).

It would also be helpful to draw a line in the sand for when firms should stop applying for registration under the MLRs and instead apply for authorisation under the new FSMA regime, and what will happen to cases in progress.

Finally, the MLRs will need to be amended to switch off the registration requirement for FSMA-authorized firms. It would also be an opportune time to clarify some of the other aspects of the MLRs, including those noted in this article.

All graphics sourced from Future financial services regulatory regime for cryptoassets: Consultation and call for evidence

Authors: Bisola Williams, Emma Tran, and Bradley Rice, Ashurt.