Writing recently in The Guardian, entrepreneur, scientist and author Gary Marcus, who founded machine-learning company Geometric Intelligence, expanded at length on his honestly held views that he does not think that “we will get to an AI that we can trust if we stay on the current path.” Much of his critique is directed at Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAi, whose growing power and influence concerns him.

Altman has said in public, before the Senate, that he favors AI regulation, telling his audience: “My worst fears are that we cause significant – we, the field, the technology, the industry – cause significant harm to the world.” But just one month after those remarks, Time published a story revealing that Open Ai Lobbied the EU to Water Down AI Regulation.

The debate around regulating AI is global in scope, and often contentious. On the one hand are a group of global tech giants, billionaires who do not necessarily hide their dislike for any form of regulation. Their ideas and ambitions in relation to AI are being challenged by state agencies, governments and individuals like Marcus.

He is suspicious of the motives of the growing power of the so-called tech bros such as Altman, but also critical of technical aspects of the technology – questioning whether they mean it can ever be intrinsically safe. Large language models, he says: “are recalcitrant, and opaque by nature – so-called ‘black boxes’ that we can never fully rein in.”

Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

But, he says: “I don’t think we should abandon AI. Generative AI is unlikely to do the trick, but some future, yet-to-be developed form of AI might.” He concludes: “One thing I can guarantee is that we won’t get to AI’s promised land if we leave everything in the hands of Silicon Valley.” Which leads us back to the issue of regulation – and international cooperation to achieve an effective iteration of it.

Last May, the World Economic Forum identified 37-AI-related bills that had been passed around the world in 2022. Since then we’ve seen the US Copyright office launch a consultation on copyright and AI, congressman Adam Schiff’s Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act, and the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, to name but three initiatives.

EY’s analysis of eight jurisdictions, Canada, China, the EU, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, the UK, and the US, reveals six key regulatory trends.

- AI regulation and guidance tends to be consistent with the core principles for AI defined by the OECD and endorsed by the G202. These include respect for human rights, sustainability, transparency, and strong risk management.

- The approach to regulation is risk-based, driven by perceived risks that specific AI systems pose to core values such as privacy, non-discrimination, transparency, and security.

- Varying use cases mean some jurisdictions are focusing on the need for sector-specific rules, in addition to sector agnostic regulation.

- AI-related rulemaking is being carried out within the context of other digital policy priorities such as cybersecurity, data privacy, and intellectual property protection – with the EU taking the most comprehensive approach.

- Regulatory sandboxes are being used to enable the private sector to collaborate with policymakers in developing safe and ethical AI systems, and rules that will support their future development. There is a particular focus on higher-risk systems where closer regulatory oversight may be appropriate.

- International collaboration in understanding the risks that might arise from the most powerful AI systems, and working toward addressing associated safety and security threats, is increasing.

A case for India

It’s worth noting that there is no mention of India in EY’s 21 page-long analysis. It seems to be the elephant in the room. There does seem to be a reason, of sorts, provided for that. According to the paper, the eight jurisdictions listed above “were selected on the basis of their legislative and regulatory activity around the topic of AI and their broader market reach.”

It is no secret that AI-related legislation in India is almost non-existent. According to experts at Morgan Lewis, Indian efforts around AI-regulation seem to be limited only to introducing some initiatives and guidelines on how to develop and deploy the technology ethically. However, “there are currently no specific laws regulating AI in India.”

But the same experts also believe that India’s vast high-tech labor force, together with millions of dollars of foreign investment, “is putting it on pace to become a major player in the global technology supply chain.”

At the same time, the non-existence of any concrete regulatory process or legislation around the development of and use of AI in India must ring alarm bells. AI-related risks are of global nature and can affect systems and operations far beyond geographical boundaries. And that’s precisely why the omission of India from EY’s analysis is questionable, especially if factors such as global reach were key in the analysis.

Photo: Pallava Bagla/Corbis via Getty Images

Another noticeable theme in EY’s analysis is the strong seam of worry that runs through these regulatory trends. We could be approaching the regulation of AI from a basis of the opportunities it creates, but instead are seeking to assuage fears. This may, to some extent, be inherent to the regulatory process, or it could be a natural reaction to some of the more extreme enabling views that essentially argue for AI to develop entirely unfettered. The type Marcus is worried about.

Once again, it’s interesting to look into India’s somewhat different, middle-path, approach to AI regulation. High-ranking government officials have recently made it clear that, while they are all for regulating AI, it (regulation) should not come at the cost of innovation. IT Secretary S Krishnan told a business summit earlier this year: “Innovation needs to be encouraged”, and that the government will make sure technological advancement around AI is protected and guaranteed.

Direction of travel in the UK remains unclear

Contrast the absence of India with the profile of the UK in analysis of how AI is being developed. While, according to figures quoted by The Guardian’s economics editor Larry Elliott: “The US and the UK have 5.22 AI startups for each 100,000 inhabitants; Germany has 1.9,” the portrayal of the UK as vying with the US for leadership in the AI race arguably owes more to hyperbole than hard facts. The scale of the US industry far outstrips the UK’s.

And while in its manifesto for the UK’s recent General Election, the Labour Party said it would ensure that “industrial strategy supports the development of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) sector,” and that the resulting development and use of AI is safe by “introducing binding regulation on the handful of companies developing the most powerful AI models,” events in the admittedly early days of the new government have raised doubts about what these signals might translate into in reality and where precisely the UK’s strategy on AI is heading.

First, there was no AI Bill – as many expected there would be – in the King’s Speech that set out the legislative program for the Parliamentary session. In its place was a commitment to “appropriate legislation” for companies developing AI models.

Then, funding of £1.3 billion ($1.66 billion) was pulled from AI and tech projects announced by the previous administration as the new Chancellor got to grips with what she claimed was a £22 billion ($29 billion) hole in the nation’s finances left by her predecessor. The exascale computer recommended by the government Future of Compute Review is no more; the AI Research Resource left hanging by the cancelation of £500m ($638m) of funding promised in addition to the £300m ($383m) it received when established in January 2024.

Photo: UK Parliament/CC BY 3.0

Instead there is an AI Opportunities Action Plan which aims to help the UK AI sector “scale and be competitive globally.” Trade body techUK is so far underwhelmed, with director of technology and innovation Sue Daley telling Computer Weekly: “Investment in large scale computers is vital for the scientific breakthroughs that will grow our economy and improve our lives. The UK had sent clear signals about its ambitions to host a new generation of computers to enable cutting-edge research, including in AI.

“In an extremely competitive global environment, the government needs to come forward with new proposals quickly. Otherwise, we will lose out against our peers.”

The government says while funding commitments were made by the previous government, the money was not allocated in its budget, and so all it is doing is acknowledging it can’t spend money it hasn’t got. And the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology did announce £32m ($41m) of support for 98 AI projects on August 7.

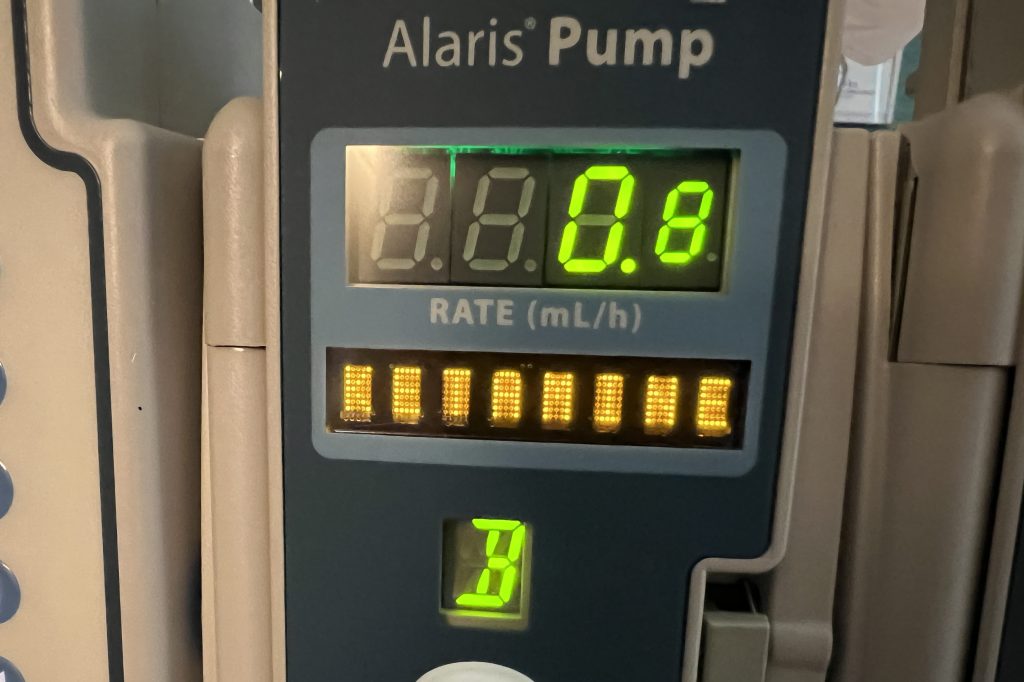

These include AI software to help people train to work on construction sites, to help improve the efficient delivery of medical prescriptions, and a system to “monitor, manage, and identify defects on rail infrastructure across the country” – a crowd-pleaser for beleaguered users of the UK’s transport system if ever there was one. The thinking is influenced by a desire to use AI as part of the wider effort to drive economic growth and development rather than fixate on AI as an end in itself.

By the people, for the people

Wherever Ai is discussed, what has been termed “AI anxiety” is very real. But research by Gartner indicates that fears – particularly those about job loss – are dispelled when people actually use the technology. “Once people are actually exposed to AI and asked to make use of it, their concern about job loss drops significantly – from around 60% to just 14%,” Gartner VP analyst Svetlana Sicular told a conference in July.

“Most people still don’t understand what AI entails. They see it as a science fiction concept or through the lens of sensationalist media stories,” she continued. “The truth is that AI is complex, and its ethical and technical nuances are not widely understood.”

She argued that if more people viewed AI as a collaborative tool for enhancing efficiency rather than something that can deliver perfection, we could move closer to achieving the technology’s true potential and reducing people’s fears.

Giving people the chance to experience something does generally improve their understanding of it. Giving them the chance to shape how they experience it would surely improve both trust and the quality of work – a point that leads us to the missing link in much of the conversation around AI regulation. In short, what about the workers?

Much of the conversation about AI development, and tech development in general, is driven by tech companies, a handful of powerful tech billionaires, and governments. The people who will be using the tech, and who will be affected the most by it, rarely get any input. And that is a model that is being challenged.

Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images

The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) recently published an article entitled We Need a Worker-Centric Approach to AI Policy. In it, CIGI argued that “We need to change our traditional approach to policy making, which typically relies on industry and government experts to draft sector-specific and tech-friendly policies, followed by periods of public feedback that have little impact.” And it pointed to the Biden administration’s “worker-centered” strategy as evidence of this approach being put into practice.

What that policy does is recognize that “that policies benefiting people as consumers should not undermine them as workers.” That is significant, not only because of the implicit assertion that the people who do the work are well-placed to develop policy on how work is done, but also for its recognition that people have multiple identities.

Much has been made of the balance between agile innovation and careful regulation, but this balance isn’t peculiar to AI – it’s something regulators grapple with wherever regulation exists. Those warning against stifling development in the tech sphere can too easily sound as if they are arguing to be left to do exactly as they want.

Getting the regulation of AI right is important for us as a species, and for the societies we live in, but also for restoring faith in a sector that is gaining an increasingly poor reputation. That isn’t only due to some of the ideas propagated by billionaire tech bros such as Marc Andreessen and Elon Musk, but also to recent findings about how some of the biggest firms have acted in terms of competition and respect for individual privacy.

As Ezra Klein concluded late last year in a New York Times op-ed on technology’s battle of ideas: “Trust is the most essential technology of all.”