I say it every year, but here goes: I cannot believe we’re in December. And as is common for this time of year, a lot of us are looking back on our work and assessing the job performed and the road ahead. Looking back at what our own organizations did correctly and not-as-correctly, reflecting on what pitfalls faced other businesses, and generally examining regulatory compliance trends can help us all prepare for the coming year. The future is shaped, at least partly, by the stories of today.

If nothing else, this year has been an active one, with the SEC in particular releasing new rules, amending others, and offering its guidance and priorities; but activity has defined other US regulatory bodies and state financial services watchdogs, too, on topics as diverse as the use of artificial intelligence and the names of funds.

Certain trends unique to this year, especially those involving new technology and the risks associated with their use, combined with the ongoing challenges posed by hybrid work arrangements, will have lasting implications for financial advisory firms and their compliance programs.

Culture and conduct

Trending topics in this area include a focus on harassment and discrimination in the corporate workplace, diversity and inclusion issues, creating a speak-up culture, and drafting a code of conduct that is actually used and suits the business – all of which are essential components of successful compliance and ethics programs. I want to focus on the first two.

Harassment and discrimination are certainly not new to workplaces, but they pose new challenges for employers as they continue to take different forms. Online tools and work-from-home arrangements mean employees can get subjected to harassment in an array of online formats – for example emails, texts, chats and gifs.

Workplaces you would normally consider or certainly hope to be havens of staid professionalism are being called toxic places of rampant sexual harassment, discrimination and otherwise inappropriate behavior, such as a federal banking regulator – the FDIC – and, also this month, the third-largest US bank.

Despite having a policy explicitly banning executives from having romantic relationships with supervised members of staff, McDonald’s former CEO, Steve Easterbrook, violated the policy and then lied about it, getting fined $400,000 by the SEC for “concealing the extent of his misconduct.”

Like nearly all corporations, Comcast has a code of conduct that details its commitment against harassment in all forms. It did not prevent it from needing to fire Jeffrey Shell, CEO of NBCUniversal (which is owned by Comcast) due to allegations of sexual harassment.

Antisemitism is an increasing concern, and that was true even before the current war between Israel and the terrorist group Hamas, which has only heightened it. When corporate leaders feel free to express their opinions and showcase their prejudices, all other stakeholders associated with the business must assess their risks accordingly.

And when training programs at businesses create or reinforce discrimination that harms consumers, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is keen to step in. Citi was recently fined for allegedly discriminating against Armenian Americans in violation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, thanks to some training in certain branches that instructed employees to deny credit card applications from people with last names ending in “yan” or “ian”.

The positive side of this coin is that city and state laws are likely to continue adding protected characteristics in the fight against discrimination (like hair discrimination laws that have passed in several states, including California and Massachusetts and protecting religious clothing and facial hair in New York) and that a number of the most populous ones mandate sexual harassment and bullying training (often annually) of businesses within their states.

Personal liability

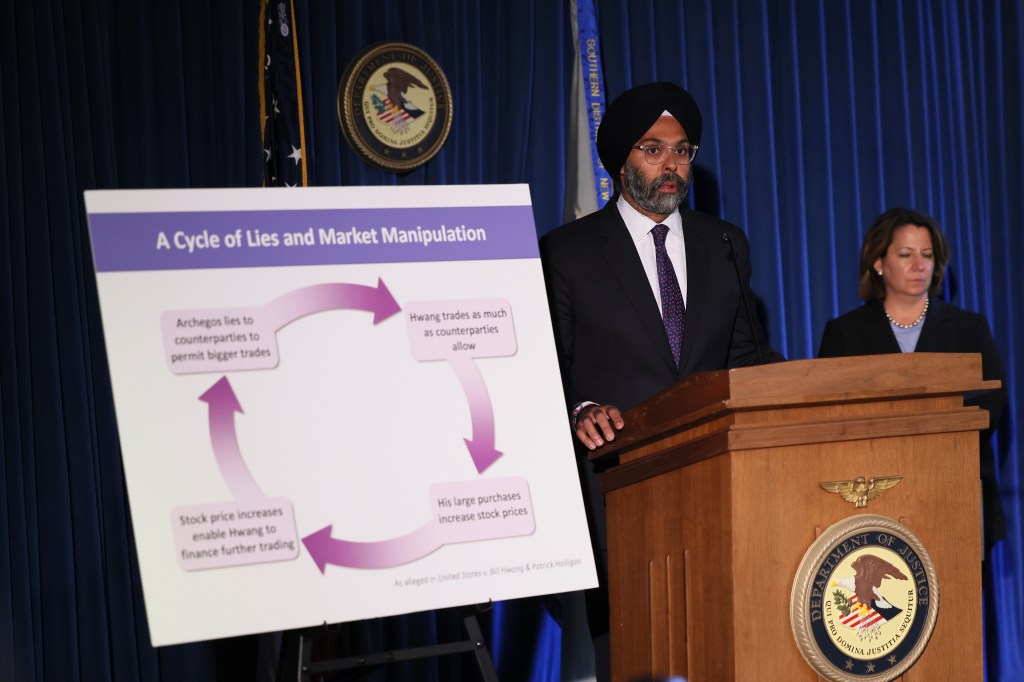

Insofar as the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) often-referenced and evolving cooperation credit regime is in place, personal liability will be a focus.

In January 2023, then-Assistant Attorney General Kenneth Polite reiterated that the Criminal Division’s Corporate Enforcement Policy aligns with its top priority, as stated in prior DOJ memoranda and public announcements: Ensuring individual accountability for corporate wrongdoing. As he stated, the Division is best positioned to secure such individual accountability when companies proactively bring corporate misconduct to its attention.

Basically, the DOJ wants companies to name names and showcase their zero-tolerance for bad behavior.

Early in her tenure, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco emphasized that prosecuting individuals accused of white-collar crime is a top priority for the Biden administration’s Justice Department.

She said prosecuting individuals prevents recidivism and improves the overall compliance of corporations. And a corporate culture that fails to hold individuals accountable often leads to “bad results”.

The SEC noted in its enforcement results for 2023 that the SEC had obtained orders barring 133 individuals from serving as officers and directors of public companies, the highest number of officer and director bars obtained in a decade. And it said “[i]ndividual accountability remains a pillar of the SEC’s enforcement program.”

A former Wells Fargo executive was barred from serving as an officer or director of a public company as part of a settlement of fraud charges for misleading investors about the success of Wells Fargo’s core business. The former executive also agreed to pay a $3m civil penalty and more than $1.9m in disgorgement and prejudgment interest to the SEC.

Additionally, the SEC has been adamant about the important role that gatekeepers, such as lawyers, underwriters, auditors and accountants, play in the protection of investors and the US financial markets. The securities regulator has said such professionals serve as the first lines of defense against misconduct and that ensuring they comply with their obligations is a critical part of its mission.

A former national office leader at audit firm Marcum LLP was charged in September by the SEC over quality control failures. The regulator said the firm’s in-house certified public accountant failed to address and remediate deficiencies in the firm’s quality control system sufficiently. He paid a fine, and he was censured and ordered to comply with certain undertakings for a period of three years, including having no leadership, management, oversight, or supervisory position at any registered public accounting firm.

In terms of chief compliance officers being held accountable, it is a great concern to anyone in this role, even though this is not a common enforcement tactic by the SEC.

What CCOs have stated repeatedly is that they just need more certainty around the decision-making process that the regulator takes in deciding to hold them accountable. Merely saying a CCO will be charged for “wholesale failures” or “active participation in the wrongdoing” is not specific enough, as CCOs point out that a number of people in the business, plus lapses that could arguably be attributable to the business itself, often play a role in cases of CCO misconduct and negligence.

For this reason, membership groups such as the NY City Bar Association and the National Society of Compliance Professionals have crafted their own frameworks to add more clarity to the decision of whether to hold a CCO personally accountable, with the hope that the SEC will adopt one soon.

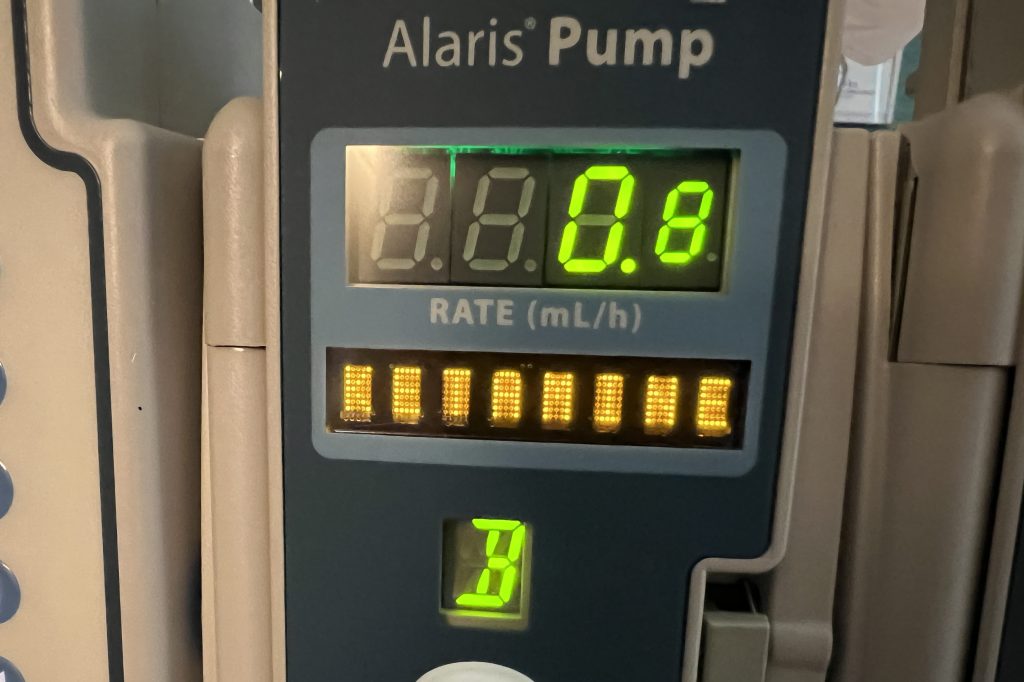

Books and recordkeeping

Let’s take a look back at how we got to today’s undeniably significant regulatory focus on recordkeeping and the supervision of off-channel communications in particular.

In December 2021, JPMorgan was fined $125m by the SEC and $75m by the CFTC for failing to maintain and preserve electronic records and for failing to supervise with a view to preserving and detecting those failures.

In September 2022, 15 Wall Street firms admitted to wrongdoing and agreed to pay penalties totaling more than $1.1 billion for recordkeeping failures. The recordkeeping requirements that were found to be circumscribed in these enforcement orders were described as “sacrosanct” by SEC officials in their announcement of the fines they brought – penalties they meted out along with the CFTC.

In October 2022, the SEC issued amendments to broker-dealers’ recordkeeping requirements designed to modernize the process in the light of technological change.

The amendments provide an audit-trail alternative allowing records to be preserved in a way that permits the recreation of an original record if that record is altered, over-written or erased.

And then 2023 rolled around. Over a dozen more businesses have been charged, again by the SEC, sometimes in conjunction with the CFTC. The charges have come against a variety of businesses, such as broker-dealers and dually registered broker-dealers/investment advisory firms, swap dealers and futures commissions merchants, and one family of firms that got a reduced penalty for self-reporting its conduct to the SEC.

What is telling about the regulatory activity in this space is how many firms were charged with the same misconduct in this relatively short amount of time, plus how adamant regulatory officials have been about the significance of the lapses and why they brought these charges in the first place.

Gurbir Grewal, Director of Enforcement at the SEC, has repeatedly noted that one of the reasons why these unarchived and unsupervised communications are so problematic is because the firms had the relevant policies and procedures in place, but employees nevertheless communicated through unapproved methods because there was widespread failure in implementing those policies.

But I think the most significant risk that regulators are so concerned about is this one: Firms not having complete records of business communications with current and potential clients makes the regulator’s job nearly impossible to perform. There is an incomplete record (or no record) for it to go on, should it need to investigate the business for some type of wrongdoing – evidence, it should be noted, that could implicate the firm or actually help it defend its own conduct.

In their press releases, the SEC continues to stress this; these recordkeeping lapses serve to impede its ability to perform its core functions. Furthermore, officials continue to express their disappointment that supervisors and senior executives, including compliance personnel, have been knowingly involved in some of these cases.

CFTC Commissioner Christy Goldsmith Romero has sounded particularly exasperated; she did not hold back in her statement on August 8 when her agency charged four financial services firms for recordkeeping lapses pertaining to business-related communications that involved some senior-level executives.

She said that, “based on the serious threat that unauthorized communications platforms pose to market integrity, the CFTC is requiring an admission of wrongdoing as part of these settlements”. And she went on to press her view that “deterrence can be achieved from a defendant having to admit wrongdoing, combined with a penalty”.

To be sure, no one is questioning the usefulness of most of these communication platforms to conduct business – certain apps notwithstanding – as they have made transacting business more expedient and efficient. If you’re over the age of 40, you will remember a time when conveniently doing business while driving in a car was not a “thing”. Today, you can do just that, plus work from home or your favorite coffee shop, all while instantly sending documents and meeting with 25 people for 10 important minutes.

But every piece of technological advancement brings with it certain risks and a need for certain guardrails, even while embracing its further development.

And while there are arguments against these enforcements – calling them overreaching, since no actual misconduct had been found in these cases – the real point of them is more existential: “We can’t do our job as regulators without these archived business communications.” Or, put another way, the “enforcement without actual misconduct” criticism is not an appropriate one here because the misconduct actually is there, evidenced by the circumvention of regulatory and (often) in-house recordkeeping rules.

Regulatory focus for 2024

Artificial Intelligence

The biggest issue we will grapple with is how many guardrails we put into place to curb obvious abuses (such as the spread of misinformation, the infiltration of illegal discrimination into data pools) that don’t also impede the promise of the technology.

Getting the balance right will continue to be a subject of study and debate, and I say this because the technology still appreciably concerns those who understand it more than most of us less tech-savvy folks.

Since some businesses have already used it inappropriately and been fined for it, and coalitions of business leaders, top government officials and consumer advocacy groups are weighing in on the topic an ongoing basis, its use must be carefully circumscribed by regulated entities. That means having policies and procedures that carefully describe what acceptable use and monitoring looks like and who permissioned persons are in this arena.

Cybersecurity

This will be a top threat for years, like it has been for many years now. This is due to the growing sophistication and global reach of hackers, how large the ever-expanding data sets are in all sectors with the potential for theft increasing as well, how lucrative hackers’ hauls have been, and (regrettably) because some businesses won’t spend the money needed to properly defend their growing operations against the cyber threat environment facing them.

Also, thanks to US government offices and high-ranking officials being seriously affected by attacks this year, the federal government (plus a number of US states) is on a tear in paying close attention to what businesses do about reporting, paying ransoms, and defending their networks.

This is because some of the same criminals strike both and are emboldened when they make off with a decent haul of either data, cash or both from the business sector.

To be sure, the reporting, chief information security officer requirements and other cybersecurity mandates that states have crafted have created a patchwork of different rules for businesses.

And the cybersecurity risk arena is so acute, and even at times bizarre, that two stories bear mentioning.

First, as I write this, Kansas courts have been relying on paper forms and faxes since a mid-October cyberattack shut down online systems.

And now for the bizarre part: A notorious ransomware gang this month filed with the SEC a “failure to report” complaint against its own victim after the alleged breach and then published screenshots of the complaint and the SEC’s auto-response on its website.

In sum, cybersecurity incidents pose a reputational risk to businesses almost incomparable to others, thanks to insinuating they cannot be trusted with any personally identifiable or other sensitive data. Never mind that the compromise of such business secrets or customer data can further serve to pummel a victim company’s stock price.

Geopolitical and sanctions risks

Advisories and proposed new rules from US regulatory agencies are being issued fairly regularly these days – so too are updated export control and lists of sanctioned entities and individuals to which they refer – and a large number of enforcement cases that allege circumvention of such lists and rules.

The nature of multinational, evolving hostilities invite an equally dynamic framework of sanctions on individuals, entities and jurisdictions. Businesses need to not only navigate these evolving lists and rules, they must demonstrate they have the policies, procedures and internal controls that can adequately monitor for internal and vendor misconduct in this risky arena.

Plus, they need a training approach that matches an appreciation for these risks to the business, based on its products, services, areas of operation, and client base to avoid the reputationally damaging and interruptive nature of sanctions investigations and charges brought in the (often politically charged) sanctions space.

Cryptocurrency

There seems to be no respite in the enforcement activity against digital currency firms – from not registering their products as securities to engaging in large-scale fraud using digital currency and distributed ledger technology.

With the fraud taking such a prominent news role and involving scams of such mammoth size, and with CEOs pleading guilty to charges and others going to prison, the great promise of the technology – which, ironically, was designed to avoid being compromised and to offer greater privacy and other protections – is failing.

The crypto industry will need more than some rules designed for fiat currency and standard clearing processes to prevent bad actors from completely undermining it, and that probably means central bank oversight and issuance of this currency.

Individual accountability and gatekeepers

The SEC has pointed to how individual accountability is a key feature of its enforcement program. As noted in its report on enforcement results for fiscal year 2023, approximately two-thirds of the SEC’s cases in FY2023 involved charges against one or more individuals. In addition, to protect investors from future violations, the SEC obtained 133 orders barring individuals from serving as officers and directors of public companies, the highest number in a decade.

It also sought to protect retail investors from the affinity frauds and other schemes targeting certain investors, such as elderly church members, Orthodox Jews, and law enforcement/first responders, among others.

Through its enforcement actions and other public statements, the SEC reiterated all year the important role gatekeepers play in the financial markets – people such as accountants, auditors, underwriters, and lawyers who share responsibility for protecting investors and play critical roles in the capital markets as the first lines of defense against misconduct.

Ensuring that they comply with their obligations is a critical part of the SEC’s mission, the agency said.

The Marketing Rule and Names Rule

Both of these rules were repeatedly mentioned at the National Society of Compliance Professionals’ annual conference in October. They will be used in cases against businesses that don’t invest most of their assets into the types of assets their names suggest (Names Rule) or that fail to substantiate any claims that might entice an investor to put money into their funds (Marketing Rule).

Indeed, the Marketing Rule has been used already; in charges that mark the first violation of the agency’s amended version of the rule, the SEC brought charges against Titan Global Capital Management USA LLC in August.

And nine firms were charged in a sweep in September. All of these cases involved the use of hypothetical performance metrics in advertisements that were misleading.

Neither rule is an “ESG Rule” or in any way supposed to fill in a gap in rulemaking in the ESG arena. But both rules have clear implications for how corporate ESG-related representations can be portrayed to the investing public, since they seek to make firms accountable for how they entice investment from the public with labels, descriptions, and data.

Election Year

We have all of next year under the Biden administration, so the activity levels seen at the federal financial services regulators should remain high.

If there is regime change, there likely would be significant pullback, affecting penalty amounts, types of cases pursued, fewer or no monitorships imposed in cases, and specific rules on ESG-mandated disclosure by regulated firms (expected to be announced by the SEC soon and already being implemented by large states and economies such as California) revoked or overridden by federal mandates.