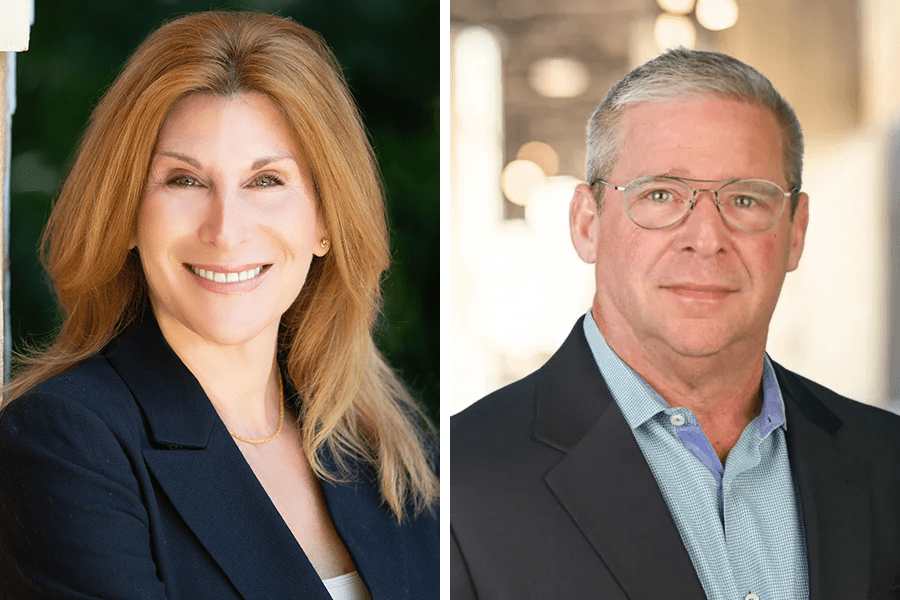

6 December 2024 by Joe Leahy and Tina Hu in Beijing, Chan Ho-him in Hong Kong

Exporters normally do not welcome news of tariffs. But in the southern Chinese manufacturing heartland of Foshan, Donald Trump’s threat late last month to impose an additional 10 per cent tax on imports from China was greeted with relief.

Trump had vowed earlier in his re-election campaign to levy 60 per cent tariffs on Chinese imports, a level that would have hit Foshan’s manufacturers of home appliances and fittings hard.

“If it really was going to be 60 per cent on top of the previous tariffs, then that would be really disastrous for made-in-China products going to the US,” says Ken Huo, supervisor at Foshan Foreign Trade Association. But 10 per cent, even if it is imposed as soon as Trump takes office on January 20, looks manageable by comparison.

Trump’s return to the White House will pose one of the sternest tests yet for China’s manufacturing and export sector, which in just two decades has become the world’s most formidable industrial machine.

As domestic demand suffers from a deep property slump, Beijing is increasingly dependent on export industries to prop up the world’s second-largest economy.

Advanced manufacturing is also at the core of President Xi Jinping’s longer-term strategy for China. His vision of “national rejuvenation” — restoring China to what the Communist party sees as its rightful global pre-eminence — depends on ending its reliance on western technology and manufacturing.

Xi’s government is redirecting investments away from real estate and infrastructure into advanced industries. As domestic wages and profits stagnate, this is supercharging the price competitiveness of the country’s exports on international markets and scaring those — including the US — that are already running large trade deficits with China.

“It is a level of dominance that we have rarely seen in history,” says Arvind Subramanian, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, of China’s manufacturing prowess. “And of course, the problem is, it’s getting stronger.”

“It is a level of dominance that we have rarely seen in history.”

But some believe Beijing risks becoming overly dependent on manufacturing. Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis, says China accounts for only 15 per cent of global consumption, less than its 18 per cent share of world GDP and far below its 30 per cent share of manufacturing. That made it reliant on demand in other countries to absorb its enormous excess production.

“The protectionism that China will face in the future will certainly not stop in the western world . . . and it’s only going to accelerate,” says Garcia-Herrero.

“At some point, China will need to rethink industrialisation as the only growth strategy available.”

Most scholars agree that China’s rapid rise in manufacturing has no parallel since the US overtook Britain early in the 20th century.

It is now the world’s “sole manufacturing superpower”, according to Richard Baldwin, professor of international economics at IMD Business School in Lausanne, who estimated in January that China’s share of global gross production had risen from 5 per cent in 1995 to 35 per cent by 2020 — three times that of the US and more than the next nine countries combined.

Its share of global manufactured exports was 20 per cent in 2020, up from 3 per cent in 1995 and dwarfing the US, Japan and Germany. Out of a total of about 5,000 products, China held a dominant position in exports for almost 600 in 2019, at least six times greater than for the US or Japan and more than double that of the EU, a paper by economists Sébastien Jean, Ariell Reshef, Gianluca Santoni and Vincent Vicard last year showed.

Since then, China’s exports have roared further ahead and are expected to rise by 12 per cent in volume terms this year, according to Goldman Sachs.

China’s obsession with production stems partly from its historical scarcity of goods and partly from Marxist philosophy, which stresses production and eschews consumption. Manufacturing is also an integral part of Xi’s comprehensive view of geopolitical security.

“For a lot of reasons — for security purposes or whatever — you can see the government really emphasises the production side, the supply side, the manufacturing side,” says Tu Xinquan, dean of the China Institute for WTO Studies at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing.

Beijing has complemented China’s natural advantages — a large population, a big economy and market, and talented private entrepreneurs — with policies such as Made in China 2025, which set targets for market share in areas ranging from electric vehicles and robotics to aerospace.

Manufacturers in China benefit from state investment in infrastructure, cheap government bank credit and investment from state-backed venture funds. Central and local governments also offer subsidies for factories and other support for favoured industries.

The government restricts capital flows and manages the exchange rate, while the hukou social structure created by the Communist party, which restricts where citizens can register to live, has helped create a large pool of low-income workers, according to Garcia-Herrero.

But the special sauce, say economists, has a distinctly capitalist flavour. “We really have very fierce competition in the China market and you can see that in most Chinese manufacturing industries,” says Tu.

Photo: Hu Chengwei/Getty Images

Rivalries have intensified following the downturn in the property market and a corresponding weakening of household demand. China’s producer prices index, a measure of factory gate prices, has been in deflationary territory for two years, while the profits of China’s listed companies are set to decline for the third consecutive year in 2024.

Yet policymakers are doubling down on manufacturing. China’s nominal fixed asset investment in manufacturing is expected to grow 9 per cent this year compared with 6.5 per cent last year, according to Morgan Stanley estimates.

“Producer price deflation in China is not just hurting companies at home, but is now . . . affecting companies globally.”

This threatens to create even more industrial capacity in a country where domestic consumption accounts for about 55 per cent of GDP compared with 70 per cent in rival exporters Japan and Germany, and 80 per cent in the US.

China’s dominance of green industries such as electric vehicles, solar panels and batteries has already led to trade restrictions from the EU and the US. And its sluggish domestic demand is causing overcapacity across many other manufacturing segments, analysts say.

“What’s so frustrating is that everyone keeps talking about the EVs when what they should be talking about is the other 98.2 per cent [of China’s trade with the rest of the world],” says Jens Eskelund, president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China.

“Overall, China’s exports to the EU are doing extremely well, while exports from the EU to China are stalling,” he adds. “Producer price deflation in China is not just hurting companies at home, but is now exported and is affecting companies globally in the process.”

William Fung, group deputy chair of Hong Kong-headquartered supply chain and distribution conglomerate Fung Group, says China’s inability to raise domestic consumption has left it in an unenviable position: weak demand at home and trade-related tensions abroad.

“I think that’s obviously leading to a very dire and competitive situation inside China and even on the export side.”

Few places in China illustrate the difficulties facing the country’s manufacturers and the dynamism of some of its entrepreneurs as clearly as Foshan.

For decades, this industrial town in the Pearl River Delta so dominated the building materials industry that its slogan became “you jia jiu you Foshan zao” — “Where there is a home, there are products made in Foshan”.

“Almost every sector of the industry benefited from the booming property market in China and the export market until 2019,” says Huo, of the Foshan Foreign Trade Association, from his office in one of the region’s huge, partly empty home decoration malls. “Now the game has changed.”

Last year, Foshan’s total import and export value fell 10.5 per cent, a trend that has continued into this year. The signs of the decline are everywhere. Tang, an employee at a Foshan high-end door producer who identified himself only by his surname, says prices for his products had halved and his distributors were lucky to make one sale a month. “Many small factories have gone out of business,” he adds.

Huo says the downturn had pushed even manufacturers that had never exported before to consider selling overseas. “Some factories . . . don’t have the DNA for international trade, but they have to try.”

His team is helping producers to use social media and online marketplaces to market their goods abroad. Huo has also moved deeper into services, offering foreign customers a one-stop shop for fitting out big projects such as hotels.

Another common strategy in China is “desinicisation” — setting up factories in other countries, especially in south-east Asia, to distance one’s products from China itself.

“There is a lot of pressure for the Chinese to now go abroad, as far as bypassing some of the geopolitical constraints on their exports, particularly to America and to Europe,” says Fung.

In a recent survey by the British Chambers of Commerce in China, 61 per cent of services firms said they saw an opportunity in helping Chinese companies move into foreign markets. “UK services have . . . found genuine business opportunities in helping Chinese businesses to go overseas,” says chamber chair Julian Fisher.

Still, many factory owners in China struggle with shifting manufacturing abroad. In China’s other great industrial region, the Yangtze River Delta, Tao Jin, chair of Zhongnan Industrial Group, says it is hard to replicate China’s workforce in another country.

Zhongnan, which makes products such as window seals for the auto industry, also has a presence in Mexico and Singapore, but Jin says workers in his Chinese factory in Suzhou have learnt the famed Toyota Production System for reducing waste and improving efficiency. “Chinese workers generally are willing to work longer hours for higher income. They don’t mind working overtime,” he adds. “The rest of the world cannot compete on cost control.”

Ecovacs Group, a maker of high-tech robotic vacuum cleaners, lawnmowers and other products also based in Suzhou, says it has no plans to shift manufacturing abroad, though contract manufacturers could be used if needed.

David Qian, the vice-chair of Ecovacs and head of its robotics unit, argues that for high-end manufacturers China’s ability to quickly conceptualise and bring products to market and its deep pools of technical talent are unparalleled. The Ecovacs brand has risen over the past decade to take 30-40 per cent domestic market share and about 20 per cent of the global market, Qian says.

He cites a feature on one Ecovacs product — a brush that extends out from the robotic vacuum cleaner into hard-to-reach corners — highlighting the delicacy and precision of its componentry. “There’s no knowledge, or no ability for that, in Vietnam or in Mexico,” he says.

But he cautions that China’s manufacturing sector had become so hyper-competitive, it reminds him of an old Chinese saying: water can carry a raft, but it can also sink it.

“China, through this superb, efficient supply chain, makes manufacturing really easy,” Qian says. But this supply chain has lowered barriers to entry, leading to intense competition and losses for some companies because “it’s just too cut-throat”.

At a roundtable with Chinese and foreign bosses this month, the Chinese Communist party’s second-ranking official Li Qiang invoked Adam Smith, the father of capitalism, in his sales pitch for China.

Li told his audience, which included chief executives such as Apple’s Tim Cook, that Beijing believed in the “rationality of a global division of labour” between countries, according to one of the attendees. This borrowed the 18th-century economist’s concept that tasks can be completed more efficiently when divided up between specialised workers.

The meeting — the second such gathering in two months — is part of Beijing’s efforts to position itself as a champion of globalisation, contrasting it with an incoming US president who is preparing to launch the next phase of a trade war.

But such assurances do little to assuage worries among China’s trading partners that the country’s manufacturing leviathan will swallow up their remaining industries and leave them as consumer client states.

“There’s no doubt that the Chinese government now wants to signal to the world that they are open for business,” says Eskelund, of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. “But the problem, as you can see from the trade figures, is that it is pretty much a one-way street.”

He adds that China’s trade would start running into roadblocks next year if its exports grew at the same speed as in 2024. “I think that China actually has a quite significant self-interest in trying to address some of these potential sources of tension before things blow up in the face of everyone.”

Beijing finally announced a domestic economic stimulus package in September, but this has consisted mostly of monetary policy support for the stock and property markets. More recently, it unveiled a debt swap for local governments, but has held back from more direct fiscal stimulus.

Senior officials in Beijing remain firmly focused on developing the advanced manufacturing sector rather than the services sector more broadly, which accounts for the bulk of GDP in most advanced economies.

“We’ve hit the peak of the traditional manufacture-and-export model.”

The Trump administration may yet force Beijing to move more quickly to a domestic demand-driven economic model. In addition to direct tariffs, his aides have raised the prospect of wider levies on goods of Chinese origin.

Jamieson Greer, who Trump has nominated as his top trade official, told the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in May that tariffs “may need to be modified to prevent third-country workarounds.”

Some scholars in Beijing and US businesspeople hope that Trump may eventually settle for a deal such as blocking imports but allowing greater direct Chinese investment in the US. Whatever Washington does, many Chinese scholars believe the manufacturing and export model might be reaching its limits in the face of persistent deflationary pressures, rising youth unemployment and falling wages at home.

“I think we’ve hit the peak of the traditional manufacture-and-export model,” says Professor Yao Yang, a prominent Chinese economist and author.

Tu, at the University of International Business and Economics, adds that Chinese exports will definitely “face more and more resistance”.

“The share of China in world exports is high enough . . . so in terms of our own economic development, we should depend more on the domestic side,” he adds. “It is already the time for China to change its economic strategy.”

© The Financial Times Limited 2024. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.