This is a transcript of the podcast SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce reflects on public service and compliance between GRIP US Content Manager Julie DiMauro and SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce.

[INTRO]

Julie DiMauro: Welcome, everyone, to the GRIP podcast. My name is Julie DiMauro, content manager in New York City. We are thrilled that Securities and Exchange Commissioner Hester Peirce is joining us today as our guest.

As you likely know, Hester M Peirce was appointed by President Donald Trump to the US Securities and Exchange Commission and was sworn into office in January 2018. Prior to joining the SEC, Commissioner Peirce conducted research on the regulation of financial markets at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. She was a Senior Counsel on the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, where she advised Ranking Member Richard Shelby and other members of the committee on securities issues. She served as counsel to SEC Commissioner Paul Atkins.

She also worked as a Staff Attorney in the SEC’s Division of Investment Management. Commissioner Peirce was an associate at Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering (now WilmerHale) and clerked for Judge Roger Andewelt on the Court of Federal Claims. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Economics from Case Western Reserve University and her JD from Yale Law School. Thank you so much again Commissioner Peirce for joining us today.

Hester Peirce: Julie, it’s such a pleasure to be with you today and to be a part of the GRIP podcast. I do want to start out with my disclaimer which is that my views are my own views as a commissioner and not necessarily those of the SEC or my fellow Commissioners.

Julie DiMauro: Absolutely. Thank you. All right, diving right in. I want to talk to you about your experiences. I can’t believe that it’s been four plus years already. I’m not sure if you feel the same way. At the SEC, what experiences stand out for you; I mean you’ve engaged in so much activity there: the business of agreeing and dissenting on proposed rules, conducting the SEC’s business during a global pandemic, your interactions with other divisions and staff within the SEC. Tell us about some of those experiences.

Hester Peirce: Well it’s certainly been an honour and privilege to be at the SEC in this capacity. As you’d mentioned I had been on the staff before and being a commissioner was not something I had imagined would be in my future, so that certainly has been a real honour. There are different pieces of the job, it’s one that’s interesting because there is a lot of variety. So I’ve really enjoyed interacting with the staff and having known how wonderful the staff are from working with them, it’s just a pleasure to be able to draw on their wisdom every day.

And then certainly the opportunity to meet with people outside of the SEC, people who are affected by the work that we do – that has been a tremendous experience for me just to learn from them, to see things through their eyes think about things from their perspective. So that’s been one of the highlights of the job as well. It’s been an interesting time to be at the Commission, spanning different Chairmen so that is a change, but also pre-pandemic, during the pandemic and post-pandemic – that also has made for an interesting number of years here.

Julie DiMauro: I bet. I read Commissioner Luis Aguilar’s statement to future Commissioners. I found it an incredible read, it was very insightful and very helpful for me to gauge what you go through during your day and what it’s like being a Commissioner. What would you say in your statement to future Commissioners?

Hester Peirce: Well, first of all, I love that he did that because it was really nice. He had been at the Commission for quite a while as a Commissioner and so he really packed a lot of advice into a relatively short statement and I think it’s a nice tradition. I like that. If I were writing a statement too, and this is what I have told people who are coming in to be a Commissioner here or at another Commission, I’d say you are an individual with your own style and your own approach and your own priorities and you have to bring that to the job as a Commissioner –that’s the reason we have a multi-member Commission. We draw on the experiences, the insights and the expertise of the different members of the Commission.

So your being a Commissioner is not going to look like anyone else’s being a Commissioner, because it really is you bringing your unique talents to the job. I see that in my colleagues at the Commission now and I love learning from them and hearing from their perspectives. Often we don’t agree on things. And that’s OK too. It’s important for people to know that you have to come in and you have to speak up for what you believe based on where you’re coming from, and obviously the goal is that you can all get to a place where even though you come from different perspectives you can agree on things.

That’s one of the important pieces of regulating the capital markets, which are not intended to be … you know, they’re everyone’s capital markets, they belong to the whole country. So I think what we want is the kind of policy that lasts well over time and that doesn’t go wildly from one side to another, but really does walk down the middle.

It’s not to say that whoever is Chairman isn’t going to be drawing the Commission one way or the other. And I guess I should spell this out right? The SEC is made up of five members, it’s a politically balanced Commission with the balance obviously being weighted in favour of the party of the President, but I think that having voices from different sides leads to steadier and more consistent policy over time, so that is something to really treasure.

So you bring your own views to the negotiations, but the goal is ultimately for everyone to be able to come together over rule changes, over enforcement actions. The ideal to have those different views shaping the policy that everyone can ultimately agree on.

Julie DiMauro: Now, on a related but more general note, what advice would you give a compliance or legal professional seeking to explore public service work in a federal agency such as the SEC? We have dedicated a portion of our GRIP site to compliance as a profession – hoping to share insights from more experienced people in the profession, also the nature of compliance in general, the chief compliance officer …

That role has changed over time. We have people with greater technological skills going into it, they’re not always lawyers, lots of different backgrounds and expertise informing the role. So if someone was interested in going to serve, going to public service in a federal agency, what would you tell them in terms of career advice?

Hester Peirce: First I would say serving as a compliance officer or in a compliance department in the private sector is in itself public service. I like to think about the way that we as a regulator work with compliance personnel to try to achieve compliance at these firms in order to protect, ultimately, investors and the markets. And so that role in the private sector is an extremely important one and people need to not lose sight of that.

But I do encourage people to come to work at the SEC. We need people with industry expertise who want to come and maybe serve for several years and then go back to the private sector; maybe spend the rest of their careers at the SEC, but bringing with them the knowledge that they had of being the ones who were on the hook for trying to figure out how to implement these rules that we put out. I find it’s so valuable to hear from our staff who have been in that role in compliance because they just understand things at such a gut level. They know what it’s going to look like when they open the federal register and look at a rule and try to figure out how to make it work with their firm’s business.

So it’s a wonderful place to work. I came here very early after law school, not having intended to work at the SEC, but having heard from my colleagues at the law firm what a wonderful place the SEC was to work. When I got here I realise the people have a depth of knowledge about the law, about the securities laws, that’s really something you can learn from. So you bring your outside industry expertise and you get this really deep knowledge of people, many of whom have been working on these particular statutes and regulations for most of their careers.

It’s a good environment to work in so I certainly encourage people to think about doing it at least for some portion of their career. And the other piece I would say is – it is really difficult to understand how the SEC works unless you’ve been working inside of it, and that was something else that I really recognized after coming from a law firm. I realised I really need to see it from the inside to get how … each agency has its own culture, its own way of doing things and it’s hard to learn that from the outside.

Julie DiMauro: Something I learned from Commissioner Aguilar’s statement was how incredibly dependent you are on your staff. I mean, there are so many people working at the SEC and everybody has a very important role to play in terms of proposing new regulations and conducting enforcement actions, and getting comments from the public. Can you talk a little about the staff and your reliance on them and your interactions with them at the SEC?

Hester Peirce: Yeah, so the staff is about 4,500 people and spread out across the country, so that’s a split among enforcement, compliance, exams and then rulemaking. And in each division there is just such deep expertise. So I am interacting with the staff all the time. Now, the way our agency is structured, staff report to the Chairman, but I interact all the time on the rules and enforcement actions and I am also interacting with exams all the time to try to talk to the people who are really eyes on the ground to what’s going on.

Whether it’s interacting with people who are issuers who are filing registration statements or whether it’s what the examiners are seeing when they are out there looking at what firms are doing, or the rule writers reacting to problems that enforcement has highlighted or that exams has highlighted for them. So, again, this has been one of the highlights of my jobs to learn from people who know such a tremendous amount.

Julie DiMauro: Like you were saying, there are people who come with their compliance and legal experience and other experiences that help the SEC Commissioners craft rules and understand their impact on businesses so that’s very important. You’ve been an advocate for the compliance community and you’ve asked your agency to not unduly burden them or place too much individual accountability or risk on their shoulders. How concerned are you about these burdens and their personal accountability risk currently. And what can compliance professionals do to better protect themselves?

Hester Peirce: I do have concerns generally about this topic because I think it’s really important to keep underscoring that the compliance obligation lies with the firm, it doesn’t lie with the chief compliance officer or her staff, it’s ultimately the firm and the firm needs to make sure that it sets aside adequate resources for compliance. Compliance is often thought of as being non-revenue producing so it’s not as exciting for firms to devote money, but really the goals should be that good compliance means a better firm that’s going to have a better likelihood of producing revenue. Everyone’s interest should be aligned in this.

To get to your real question about compliance officer liability, it’s important that we attract really high-quality people to the compliance profession. If you structure the system in a way that every time a firm has a problem you bring an enforcement action against the compliance officer, or even if you don’t bring an enforcement action you call the compliance officer in and you potentially are thinking about bringing an enforcement action against that person, that could really dissuade the kind of people we want from going into the profession. Because it’s about judgment ultimately, right? We want people who are good at exercising judgement in difficult circumstances where you have to weigh a set of facts and you have to weigh a set of very complicated rules and figure out how those interact.

So what I am concerned about is if we get that balance wrong of bringing cases against compliance officers who have really been trying to do their jobs, we will run people out of the compliance profession altogether. There are obviously instances where we would all agree that a compliance officer should be held responsible where the compliance officer, for example, helps the firm violate rules, who actively sets out to conceal documents from the exam staff, things like that I think we can all agree.

But I do think a lot about what we’re doing when we go back and we, through the eyes of hindsight, second guess how a compliance officer spent her time. Right? We know when we’re bringing a case against a firm because we see there is a violation, we know where that violation was. But putting ourselves back in the shoes of that compliance officer three years ago or five years ago did she have reason to know? Maybe she was dealing with other things. There are probably a lot of other things on her plate. So I think we really need to be very careful about that sort of Monday morning quarterbacking type of approach.

Another thing that really has me concerned in this area is – some people will say we haven’t seen too many cases of enforcement actions against compliance officers over the past several years so maybe we shouldn’t worry. But what causes me to worry is the plethora of new rules that are coming out, which are very intense and very detailed and very wide sweeping rules and those will dramatically affect the job of a compliance officer. They will certainly make many more late nights for compliance officers.

So are we going to end up turning the compliance officer’s job into just a job where she just pulls the rules off the shelf, checks and ticks off each thing that the SEC has told her to pay attention to? Or are we going to have it be what it should be, which is again we think that the compliance officer should be looking at the facts and circumstances of the firm that she is in and exercising her judgement against principles-based rules from the SEC? If you turn it into a compliance checklist job, you’re not going to attract the right kind of people to the profession.

Julie DiMauro: I know a lot of compliance officers are worried about what you just mentioned, particularly the resources issues and holding compliance officers accountable for things their firms could have, should have, intervened on earlier. And, as you (I think) put it, penalizing people for being bad at their jobs – with maybe a bar from the industry even as a penalty.

Hester Peirce: I think ‘bad at their job’ in hindsight. And I think the point you made about resources is important too, because you can see a compliance officer that sees a resources issue and tried to correct that problem. It might be better for all of us if that compliance officer actually stays at that firm and tries to get that problem fixed. So, we need to make sure to have a system where she can try to get the resources and management attention to it, although she might not be successful.

But we don’t want to hold that well-intentioned compliance officer responsible for the intransigency of the management of the firm. I’d welcome feedback, and I’ve been thinking of this for some time now, where we have some statement that explains when we’ll hold compliance officers liable and when we will not. So, if people have suggestions on that, please do reach out. I know there have been some great private sector efforts on that, and those are the ones I’m looking at and have drawn from.

Julie DiMauro: Thank you for saying that. I believe that would add some much-needed clarity to that issue and the SEC’s approach to it. Now, a professional working in compliance today is using multiple tech tools to perform their jobs in managing risk. I want to ask you about technology and how it’s transforming compliance. What are the regulator’s expectations when it comes to using regulatory technology?

Hester Peirce: I can’t speak for everyone’s uses. It can make people’s jobs easier in some ways and harder in others, and we’ve seen some recent cases in which people are using off-channel communications in ways that were not possible before. I think we need to encourage them to use tools to help them do their jobs better. Part of that, when you use a new tool, is to think of its limitations and its potential challenges that you need to compensate for in some other way.

But there also is a piece in the problems we see that are just people problems. If you don’t know the people well that you’re working with, I don’t know if you’ll be able to identify those problems, so don’t rely too much on the technology. Don’t just assume the technology will find the bad conduct in the firm. You really need to know the people too.

Julie DiMauro: Absolutely. It’s the people that add the context, judgment and relationships to these issues. And I’m glad you mentioned that regulators are using technology all the time and are advertising it. FINRA, the SEC, the CFTC – they keep saying ‘we use this stuff and expect you to do as well’ – at least in relation to their size and resources.

Hester Peirce: That raises another issue too, which is that we have all these new rules coming out, so I do fear that some firms will prioritize – well, it’s not a fear because they have to comply with our rules – but what I ask sometimes when we adopt a new rule is ‘what would that firm have been doing if it weren’t complying with the rule?’ Would it have been using it to set up a compliance system that it actually thought would work better? It would be a shame to lose the ability for firms to put systems in place that would actually help them with compliance because they are trying to check the box for our rules.

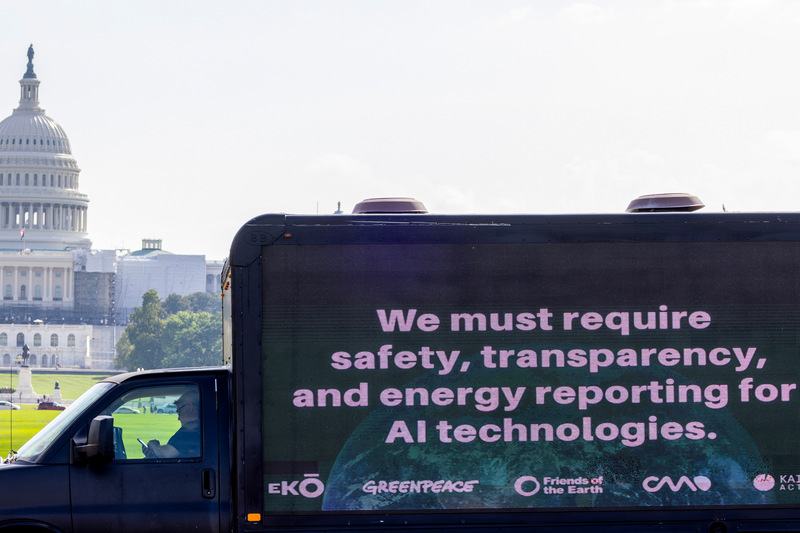

Julie DiMauro: When it comes to the emerging world of data analytics and artificial intelligence, I want to ask you what approach you think is best from a regulatory standpoint, because there are so many different ways of approaching this. There’s the ‘wait and let see’ approach, waiting for innovation to be more fully developed and understood – to one that starts out with very clear guardrails. I read your dissent of the proposed new requirements for BDs and IAs regarding the use of predictive data analytic (PDA) tools, and it was quite pointed. Can you walk us through your thoughts on this – on what you’ve called the SEC’s hostile approach to new technology?

Hester Peirce: I was a bit surprised by this proposal, and we’ll see what people have to say on the outside. I think it will be important on shaping all of our thinking here at the agency. So I would encourage people to take a look at that. This particular proposal picked out certain kinds of technology – you mentioned predictive data analytics. The definition that’s used in the actual proposal is quite broad and I found it a little bit difficult to get my arms around how much technology it would encompass – I think quite a bit.

It picked out those types of technologies and it said ‘we are going to require people to think through everything that goes on within the black box of those technologies, figure out if there are any conflicts that could potentially put the interests of the firm ahead of the interests of the client, and then we’re going to require those conflicts to be either eliminated or neutralized’. Well, that elimination and neutralization does not encompass disclosure, so this is one instance where we’re just saying disclosure is not a solution, and that runs completely counter to the traditional approach the SEC, as not a merit regulator, has taken, which is to say ‘We think that investors are able to take information and make decisions for themselves’.

So I view this a regulatory hazing. We’re picking out certain technologies and subjecting them to a level of regulation that doesn’t apply to other technologies. And that just doesn’t make sense to me. It could have the adverse consequence of firms deciding they are just not going to use technologies, particularly small firms, I think the rules would require small firms to do things I don’t think they have the capacity to do for a whole suite of technologies. So they may decide to just forgo using certain technologies that they otherwise would use, and that could adversely affect the customers. So we’ll see what the public says. Maybe my take on this is completely off base, so I’m really looking forward to getting feedback from people who would actually have to put this rule into practice.

Julie DiMauro: You have to think about investor protecting, a huge part of your role, and not hindering market development. That’s an incredible challenge when it comes to being a commissioner. How do you take that in and think about that every day and interpret that? It’s a tough judgment call, I would think. How do you make that call?

Hester Peirce: In some ways I think of it all as a very wholistic conversation. On the one hand you’re thinking about protecting investors and making sure they are getting the information they need to make those decisions. But really that’s the fuel of their own ability to make their own choices – those two go hand in hand. I don’t think we should be a merit regulator, I don’t think that’s what Congress told us we should be. Consistent with how much of the rest of life works in this country, people are free to make their own choices, sometimes those choices are not good ones. We have a role to play in getting them disclosure and helping with investor education efforts, so those have to be much more far-reaching than just SEC-run efforts.

I think we have to do a much better job of educating our children, all the way up through adulthood on investor related issues. Financial education is really important. But ultimately, what kind of a place would we be if the SEC just sat there and said, ‘you what, we’ll make your investment decisions for you’? We’re quite far from that now, but I think that sometimes we do stray into the territory of saying ‘I know what’s better for people’, even though we don’t know people’s individual circumstances, their risk tolerance, their future plans and dreams. We don’t know what their talents or their full portfolios are either. So it requires some humility on our part to say we don’t really know what’s best for people but we can give them some tools to help them make decisions that are best for them.

Julie DiMauro: Now, you are approaching the end of your tenure at the SEC. Can you hint at your future plans? I saw a speech of yours where you joked about the South Eastern Conference and being SEC commissioner – I know when I Google I have to type in SEC and then the word securities otherwise I get everything about football – so what might be your future plans?

Hester Peirce: I will say that beyond hoping someday to be a beekeeper and to learn some coding, I don’t have any plans for the future, and I don’t think that I can think about that until after I leave this job – I’m so busy with all the rules and important actions.

Julie DiMauro: I can imagine. So, from working at the securities regulator to tending the busy pollinator — I wish you continued, great success and I thank you so much for spending your time with me today, Commissioner Peirce. And a sincere thanks to everyone listening in today. Check out our articles, podcasts and more at GRIP, Global Relay Intelligence & Practice — located at grip.globalrelay.com. Have a great day.