07 February, 2023 by Olaf Storbeck in Munich

Wirecard CEO Markus Braun had barely managed to reassure shareholders rattled by news of an internal fraud investigation in 2019 when the lawyers leading the probe all but called him a liar.

The chief executive of the then-highflying German payments firm, which months before had entered the elite club of the 30 largest listed German firms, had vehemently and publicly denied Financial Times reports about alleged accounting manipulation, calling them “inaccurate, misleading and defamatory”.

There had been “no material compliance findings as to the governance and accounting practices of any Wirecard subsidiary”, he said.

But in a pointed letter dated February 13, 2019, Rajah & Tann, the blue-chip Singapore law firm in charge of the investigation, took Braun to task over these statements.

“We . . . believe that the statement with respect [to] ourselves risks being misconstrued by the public to imply that we have found the allegations completely lacking merit or credibility,” the firm wrote, adding: “We regret that we are unable to agree with the views publicly expressed by Wirecard AG and/or its CEO.”

The letter is one of several examples of Braun being accused of making incorrect and misleading statements to investors, an FT analysis of Wirecard emails and other documents reveals. The incidents raise further questions about Braun’s credibility, just as he is due to take the stand at the high profile Munich trial examining the failure of the company.

“Braun is as credible as Baron Münchhausen,” said the MP Jens Zimmermann, referring to the 18th-century nobleman famous for his outlandish stories. Zimmerman, an MP for the Social Democrats who sat on the parliamentary inquiry into the scandal, added: “A CEO who does not notice that his most important clients are not real may exist in fiction, but I am certain that Braun was very aware of his company’s situation.”

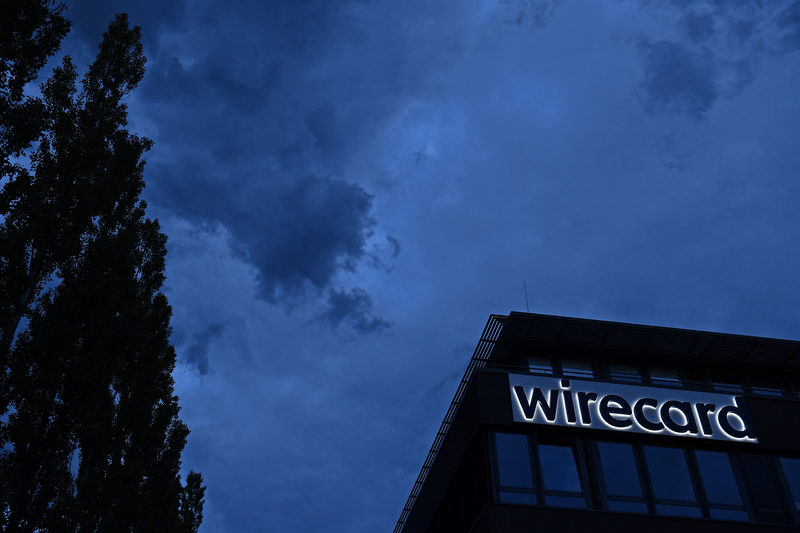

Wirecard collapsed into insolvency in 2020 after disclosing that €1.9bn of corporate cash, half of its annual sales and its outsourced operations in Asia did not exist.

Braun’s personal trustworthiness is crucial for the outcome of the criminal case against him, which started in December. The 53-year-old, who has been in police custody for two and a half years, has been charged with fraud, embezzlement, accounting and market manipulation. Two other senior Wirecard executives are also on trial.

So far, Braun has not made a statement in court. His lawyer Alfred Dierlamm has said that his client is willing to do so and to answer questions. Previously, Braun has denied any involvement in the fraud and suggested that, as Wirecard’s single largest shareholder, he is also a victim.

Braun has been implicated heavily by one of his co-defendants, the former Dubai-based executive Oliver Bellenhaus. After Wirecard’s collapse, Bellenhaus travelled from Dubai to Munich, turned himself in and became chief witness. With a lack of conclusive evidence that Braun knew about or was directly involved in the alleged fraud, the trial to an extent hinges on which man the panel of five judges hearing the case believes.

Internal emails and other documents reviewed by the FT suggest that key factual statements by Braun were not always truthful and were sometimes challenged by lawyers hired by the company and by its own auditors and supervisory board.

After an FT story in January 2019 reported that a compliance investigation by Rajah & Tann had found evidence indicating “serious offences of forgery and/or of falsification of accounts”, Braun told analysts on a call that the ongoing probe had not found “any proof, or conclusive findings, that any of these allegations are true” and was not expected to do so.

In its February 13 letter to Wirecard, Rajah & Tann countered that in its last formal update to the company it had, in fact, given the view that “many of the initial suspicions raised in our preliminary report . . . appear substantiated”.

The letter added: “Our findings following a review of accounting documents and interviews conducted with various individuals prompt us to recommend an expansion of the scope of the investigation rather than a dismissal of the allegations.” It then set out in detail some of the findings it felt merited further investigation.

The firm said it disagreed with Wirecard and Braun’s view that it “has not made, and is not expected to make, any findings of material non-compliance as to the governance and accounting practices of any Wirecard subsidiary or employee”.

It also rejected Wirecard’s suggestion that the allegations were based on flawed or forged evidence, saying: “we have not yet been provided with nor have uncovered proof of such flaw or forgery”.

Rajah & Tann added that Braun and Wirecard’s public position “causes us concern that our investigation and findings may not be properly and objectively considered by Wirecard” and urged the company to stop making public statements about the investigation “until after our final report has been issued”.

One year on, it was KPMG’s turn to tell Braun that his depiction of facts was not in line with reality. Forensic investigators from the firm had been trying to establish for months whether Wirecard’s outsourced businesses in Asia were genuine.

On April 21, 2020, KPMG told Wirecard that it had run into an “obstacle to the investigation”, that too many documents were missing and Wirecard’s outsourcing partners in Asia were not co-operating. The supervisory board subsequently extended the KPMG investigation by just under one week.

According to people familiar with the discussions at the time, the supervisory board was already concerned that Braun, who was in charge of communication with investors, would distort the facts in the required stock exchange statement.

So it provided a summary of the key points to mention in the statement, including the fact that KPMG had run into an “obstacle to the investigation” as well as the assessment that the auditors were “unable to rebut the allegations raised against the company with regard to [outsourced operations in Asia] during the investigation period”.

Braun nevertheless drafted an upbeat statement that suggested that KPMG rather than Wirecard was responsible for the delay and claimed that “to date no substantial findings have been made” by KPMG.

Before it was published, Braun shared his draft with KPMG. Sven-Olaf Leitz, the senior partner in charge of the probe, responded by email, telling Braun that his “depiction is not in line with our perception of the actual facts and does not match our written and oral reporting”. Leitz also said that Wirecard should point out to investors that KPMG had been unable to investigate “multiple issues” due to “obstacles”.

Braun would have none of this, and sent out his version of the statement after markets had closed, dismissing the input from the supervisory board and from KPMG.

When trading opened the next day, Wirecard’s share price rose 11 per cent and, in their charges against Braun, prosecutors cite this regulatory statement as a prime example of market manipulation.

Braun’s defence has contended that Wirecard had promised to submit new documents that were likely to change KPMG’s view, according to people familiar with the details, and that an external lawyer told Braun that the supervisory board’s suggestions for the regulatory statement were not in line with legal requirements.

But when the final KPMG report was published a week later, the stock fell 26 per cent in a day.

In an attempt to reassure panicky investors, Braun told analysts in a recorded call on that day that the delayed annual audit by EY would not be affected by KPMG’s findings: “EY informed us this morning they have no problems at all to sign off the audit,” he said.

At this point, the two EY lead audit partners Martin Dahmen and Andreas Budde snapped.

In a terse email to Wirecard chair Thomas Eichelmann, which was seen by the FT, they pointed out that EY had given such a statement to Wirecard “at no point”, adding that Braun’s public claim “could create misinformation in the public marketplace and wrongly suggests that we have reached a conclusion on Wirecard’s 2019 financial statements and are prepared to issue an unqualified opinion”.

Dahmen and Budde urged the supervisory board to “conduct a timely review of this matter and consider whether it is required to issue a corrective statement clarifying the status of EY’s audit work.” Internally, EY evaluated if it was legally entitled to resign as Wirecard’s auditor, according to people familiar with the matter.

That audit was never completed and Wirecard collapsed on June 25.

EY, KPMG and Braun’s lawyer Dierlamm declined to comment. Rajah & Tann did not respond to an FT request for comment.

© The Financial Times Limited 2023. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.