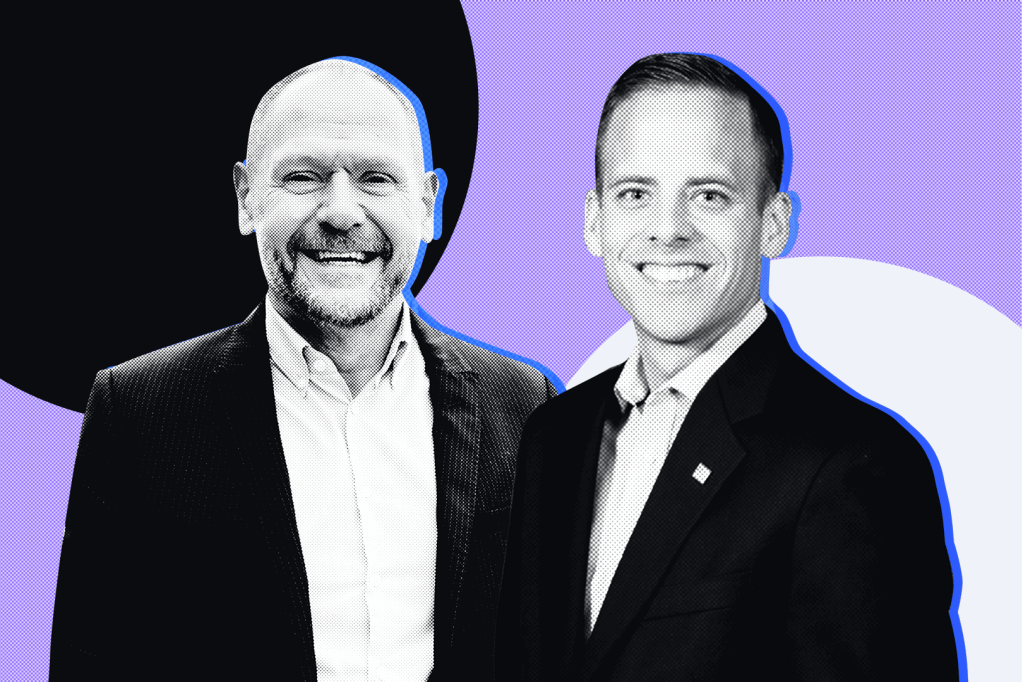

The following is a transcript of the podcast Jack Castonguay and Rob Mason on ethics and exams featuring GRIP US Content Manager Julie DiMauro and the Director of Regulatory Intelligence in our Global Relay London office, Rob Mason, and by certified public accountant and Hofstra University professor, Jack Castonguay.

[INTRO]

Julie DiMauro: Greetings, and welcome to a GRIP or Global Relay Intelligence and Practice podcast discussion. I’m Julie DiMauro US Content Manager for GRIP. Our podcast can be found along with our articles and special reports at grip.globalrelay.com. Please find GRIP there and follow us on LinkedIn.

I am lucky enough today to be joined by my colleague, the Director of Regulatory Intelligence in our Global Relay London office, Rob Mason, and by certified public accountant and Hofstra University professor, Jack Castonguay. I’ll let both gentlemen introduce themselves and then we’ll kick things off with a general intro into our topic today. Jack, please tell us a little bit about yourself, if you would.

Jack Castonguay: Of course, and thank you for having me, Julie. I’ve been at Hofstra for, I’m going on my seventh year now here. My background is in auditing and corporate governance. I was a former assurance professional for PWC, and I also currently serve as Vice President of Learning and Development for a private education company that does CPE and exam review for the exact issues that we’re going to be talking about later today.

Julie DiMauro: Perfect Jack, thank you so much. And Rob.

Rob Mason: Hi, everyone. Hi, Julie. I’m Rob, the Global Head of Regulatory Intelligence at Global Relay. I previously worked as a compliance manager at Lloyd’s Banking Group and UBS, where I was responsible for the global oversight of market abuse monitoring, and that includes trade surveillance and communication surveillance. Probably worth mentioning that before that, I spent five years with the FCA, that’s the UK’s conduct regulator, in the team which was set up to supervise their market abuse regulations.

So reviewing and examining all the regulated firms surveillance capabilities aligned with regulatory expectations. I also got involved a little bit in some of the more complex market abuse enforcement cases that we prosecuted, so that was quite good fun. But it’s really great to be here. Thank you very much for having me.

Julie DiMauro: Thanks for being here, Rob. Thank you. Now, okay, by way of background on our topic of exam cheating allegations at big audit firms, here’s just a quick refresher.

Earlier this month, in the largest fine it has ever imposed, $25 million, the US Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, or PCAOB, fined the Dutch arm of big four audit firm KPMG for widespread answer sharing when taking mandatory internal training exams. The firm’s mandatory training courses at issue here covered such topics as US audit standards, professional ethics, and independence.

The agency specifically cited the firm’s violations of rules and standards relating to its internal training program and for the lack of monitoring as it related to its quality controls. It also singled out a former head of assurance and member of the management board for what they said was substantial contributions to the violations, and they both fined and barred him from the industry. In the same press release, the PCAOB announced charges against a pair of Deloitte affiliates in Indonesia and the Philippines for similar conduct, staff sharing on internal training exams with a separate $1 million penalty for each.

This is far from the first time exam cheating has been alleged at big four audit firms. The PCAOB has sanctioned nine registered firms since 2021 in various actions and $34 million in fines in this exam cheating category in just 2024 alone. PwC affiliates this past December and other KPMG affiliates in 2021 and 2022. In 2022, the SEC brought an action against Ernst & Young in the US, handing them the largest fine against an audit firm ever by that agency, a $100 million fine for cheating on ethics exams.

Now, Rob, my first question is for you. You have specifically been focusing recently on non-financial misconduct at businesses for Global Relay, especially such conduct of financial services firms. Can you tell us a little bit about the areas you’ve focused on and the significance of these types of cases and regulatory responses to them?

Rob Mason: Yes, sure. It’s a real interesting one. And thank you very much for the intro. I’d say non-financial misconduct has been named by the UK conduct regulator, the FCA here. And I think they’ve led and picked this topic up and run with it. I think against the backdrop of UK financial services, seeing several high profile cases of what they describe as this non-financial misconduct, which has been including some very unsavory behavior by a loading asset management individual. We saw even the CEO of BP, some trouble at the Confederation British Industry, even some TV personalities and the UK’s Deputy Prime Minister had some complaints about him with regards to bullying.

This has resulted in real focus in this area in the subsequent launch of a parliamentary inquiry into sexism and misogyny in the city, which has since been nicknamed the sexism in the city inquiry. And I think that’s required the FCA, the regulator, to commit to ensuring there’s much better visibility of non-financial misconduct in the workplace. And they’ve defined that as bullying, sexual harassment and discrimination. What they’ve done is the FCA has now sent out hundreds of letters to their regulated firms and brokers to identify how firms are managing and recording these behaviors and what actions that they’ve taken.

The letter looks to go back three years and looks at the number of instances, how they were identified, whether that might be through complaints or whistle blowing or even surveillance of communications and the consequences, i.e. were they dismissed, were they upheld, etc. And finally, what the penalties or consequences were. I think it’s probably fair to say that the larger institutional banks would probably be expected to have a means to identify and review and escalate these types of issues. But there are some others that may well be struggling with this request and certainly don’t want to appear anomalous. And what do I mean by anomalous?

Well, that might be to respond with either very low or very high numbers that make them stand out from the pack, either for not finding anything or having lots of questionable conduct. So we’re going to wait for the outcome of these mandatory requests and they are mandatory. It’s notable that there are sections of the financially regulated world who are often less under the eyes of the UK regulator. And one of those examples might be the insurance firms. And certainly in London, it might be fair to say that they have a larger white male employee population. And firms clearly want to avoid that level of reputational scrutiny or damage where there’s instances of this nature. And though there’s been some limited proactive steps, but now the regulator has got involved oversight of employee conduct, having previously been seen as a nice to have, is starting to move towards a regulatory requirement. So it’s going to be interesting to see how other regulators react and review activity in this area in more detail.

Julie DiMauro: Rob can you tell me when is the regulator expecting to be informed about misconduct of this nature? Is it during the investigation before an investigation when disciplines meet it out? Has there been any discussion about that?

Rob Mason: So they haven’t explicitly stated that. And there’s obviously an obligation to be open with the regulators with regards to conduct nature, if there’s some serious enough conduct to require disciplinary action. Certainly for those regulated individuals who are registered with the regulator, they would expect to be informed as soon as those decisions are taken. With regards to this inquiry, when the results are going to be in, I think they suggested that we’re talking about after the summer. So quarter three, they’ve obviously got to sort out all the responses to these letters and correlate them into some sort of order. But I would certainly expect those firms that sit at the extremes to maybe get some sort of further follow up. And one would expect some publication bearing in mind that the FCA have been fairly public with this element and they’ve obviously made this commitment to parliament.

Julie DiMauro: Absolutely. But we’ll get back to it. But all of this brings up ideas of firm culture, their cultural environment, employees’ fitness for their roles, that type of thing. But I think we’re going to come back to that. So thank you for setting us up for that later discussion. And Jack, I want to ask you, given your background, I want to understand why this might be happening and get your CPA audit perspective on this. A little insight into what these exams are like, why this could be happening because of the nature of the exams, the nature of maybe staffing and resources at these businesses. Can you tell us a little bit about that? Give us some background.

Jack Castonguay: Sure. So most of the exams are typically in a multiple choice format. So almost like if you’re going back to university or your high school days, if someone takes the exam before you, more often than not, they’re going to see the same questions that you’re going to see later. So if one person takes it, you see the exams. So the exams are only based on either some standards. You have some exams that are more based on ethics and independence rules, like what type of clients can you take on, what fee arrangements can you have for those clients. But at the end of that area, you take whether it’s an hour, you have between three to five questions and that scales up per each hour. And I think what we’re seeing now is there’s a huge pipeline collapse, particularly in the United States, where less and less people are going into accounting as a major.

So colleges and universities have less accounting students. Less people are becoming CPAs. The number of new CPA candidates has fallen by more than a third since 2016. And because of that, more people on the job are stressed. They’re working more busy seasons. They’re working more clients. It used to be in audit and in tax, you were slammed January to April. Now you talk to people at firms and they’re slammed January to December. This is too much work and not enough staff. And when you have that, the last things you want to do is spend eight hours taking an internal training course and then an exam afterwards. Because a lot of the courses, if they’re on demand, you just take an exam at the end. So sometimes you can skip through it. Sometimes you can’t. But if you pass the exam, oftentimes you get the credit. So what we’re seeing, it looks like at least on the outside, is these people are stressed, they’re pressured on time and the exam takes away billable hours time.

So it’s likely that they’re now trying to cut corners and save themselves some time by cheating. The counterpoint to that is, is maybe this has been going on the whole the entire time. And now we just have better ways of tracking it. I think when I read the report for KPMG Netherlands, if you look at it and said they found they were sharing the games through electronic communications. I’m assuming that’s something like Teams or whatever internal chat function they use. So it’s possible that this is a newer phenomenon, but it’s also possible that this has been ongoing. Now we just have more of a digital record behind it. And it is unfortunate though, when you when we’re tasked with the public trust, right? CPAs are ultimately accountable to the public. We issue audit opinions. So if you don’t have the public trust, what does that opinion mean? It’s not worth the paper is written on. I generally think I when I looked at it, you see some of these cheating scandals are focused around ethics exams. And cheating on an ethics exam is to me almost as bad as it gets, right? You’re supposed to be focused on ethics. And you’re literally cheating on a thing that tells you don’t cheat. So I think that’s been more of a struggle. But I do think a large component of it has been focused around the work pressures, the lack of available staff, and people not being able to just take the time and not losing client work as a result of that.

Julie DiMauro: That makes sense. And these exams are to maintain their certifications?

Jack Castonguay: Yeah, it looks like some of them were just internal training. But a lot of them, if you’re a if you’re a certified CPA, like I am, you have to have about, in most jurisdiction, you have to have about 40 hours of training annually. And a lot of states, I’m licensed in Virginia and New York, I’m required to have one of those or two of those hours the ethics exams as well. So that is just to keep your license up. But also the firms even for their staff that aren’t licensed. So if you’re not a CPA, a lot of these things are just to inform staff. There’s a lot of in the profession is kind of self regulated, which we’re saying. So for example, you know, you have to know that you can’t own stock in the company that you’re auditing, right? So if I’m auditing XYZ company, I can’t own stock in there.

But whoever the audit firm that employs me, whether it’s PwC, KPMG or some other firm, they don’t actually go in and look at my E-Trade account or my brokerage account. I just have to self report it. So some of these trainings are just to make sure you understand what you can and can’t do on the job. And then others are just going to be more focused on what are the new standards? What do you need to know? What constitutes audit evidence? What constitutes a properly structured lease? And how do you identify one? So it’s a little bit of just internal, hey, here’s the rules you need to follow up. And also a little bit of, hey, here’s the standards and the rules that you need to be up on so you can go and then do your job.

Julie DiMauro: Okay. Now lawyers have to maintain continuing legal education depending on the state in which they’re barred. Investment advisors also have certifications and licenses. So I just want to point out it’s a number of different industry sectors have exams. But are there a lot of changes year to year in the exams with regard to the content of the exam itself, Jack?

Julie DiMauro: It will depend. Like if it’s a brand new course, obviously if they’re, I’m not going to have seen those questions before, but no, I mean, some of these rules haven’t changed in the last century, to be honest. Some of them haven’t changed in the last 10 or 20 years. So if you’re taking a course on it, you’re probably going to see the same questions that you would have, that someone else maybe at your firm would have seen a year or two before, or whether they took it six months ago. Because luckily, both in a good and bad way for accounting, we tend to be quite slow moving, regulations tend to be quite slow moving, and standards tend to not keep up with the times often. So oftentimes these exams are going to be the same thing you’ve seen before. The content is going to be the same just because they haven’t changed. And one of the things, if it’s not broke, don’t fix it. So oftentimes you can go in and you’re going to see the same questions. Maybe you saw last year, two years, and you’re definitely probably going to see the same questions that your colleague took, you know, a week or two before you did, or an hour or two before you, which seems to be in some of these cases.

Julie DiMauro: Thanks for that background. Rob, do you want to jump in at all?

Rob Mason: I was only going to add that it does feel rather like those taking those exams are seen as the sort of gatekeepers and advisors who are helping others in the community when they get into trouble. So there’s this kind of presumed trust that these advisors are well qualified to give others advice, which makes one feel that the real sort of integrity of the relative individuals involved is really questionable. You know, should they be giving advice to anybody?

Julie DiMauro: Good point. Now, I think my main concern in this area is the fact that the behavior continues. I mean, in the intro, we talked about, you know, several years of this occurring, or at least us detecting it through regulators and their technology. So, you know, we’ve had regulatory action, levied fines. Cheating got a lot of news coverage, actually, and people were held individually responsible, but it just continued. I think that should be of concern to leadership teams at audit firms.

It signals to me that there’s not enough deterrence here. So I want to talk about deterrence, wondering if we should start clawing back compensation, adding specific ethics and conduct metrics to performance reviews, promptly disciplining employees at all levels for these infractions. I’d love to hear your thoughts on all of these things, clawbacks, discipline, other incentives, disincentives. So let’s start with you, Rob, if you don’t mind.

Rob Mason: Yeah, sure. I mean, I think to Jack’s point as well, you know, sharing answers to an exam may have happened previously and not been identified. It might not have been seen as such as a big deal, maybe. And I think we’ve seen now a number of instances, including ironically that big four consultancy cheating on ethics, which is just unrideable. It’s incredible, isn’t it? But that’s also led, I think, because of the nature of that issue to some serious media coverage and serious reputational damage which has impacted those various business activities and I guess, ultimately, revenue.

The cases also have suggested that there’s been some senior executives involved. So it’s senior folks often getting their executive assistants or their personal assistants to complete the exams on that computer-based training on behalf of them. Generally, again, suggesting that there’s a time or there’s a rationale for justification is they didn’t have the time to do it. I’d also note that, you know, I’ve seen this in my experience of overseeing a banking training program to the extent where we’ve spotted through communications monitoring that answers are being shared and, you know, senior members of the firm are doing this. That sends a very poor message from the top and cascades down.

I think to answer your question, it feels a bit like there’s a time issue which makes the slump somewhat justifiable. I don’t see that myself. But it feels like not having the time to revise an exam on ethics and then advising others on it seems unreasonable.

Steeping those heavier fines and the compensation for them. I mean, what I would say is that there are some parallels in other issues and there are consequences to all actions. We were looking at this from an angle of communications monitoring and we saw a number of record-keeping issues where numerous firms were fined by the SEC for non-approved communication channels for business purposes. And as that penalty became higher, obviously the consequences became larger too.

So previously we might have found an instance where somebody was saying, oh, I’ll call you on a different line. And that might have ended up being a level one policy reminder where there was a penalty if someone were referred to speaking on a non-monitored communication channel post the fines. Colleagues were found to be using that and the expectation was possibly a disciplinary or a compensation sort of impacting action. So it’s all around that action and consequence with regard to being a credible deterrent as well as clearly articulating so everyone knows what’s going to happen if you do something wrong.

Julie DiMauro: Perfect. And Jack, what do you think about deterring on this type of behavior if regulatory fines and enforcement actions have not worked thus far?

Jack Castonguay: Yeah, Rob, I think you make a good point and I’ll be interested actually to get your thoughts on this. But, you know, I know going back, I had some clients in practice to where their internal control function, which is really what we’re talking about here at the company, their internal quality control, is they were compensated based on essentially the output of the control. So if the control that you were assigned to, if that control was effective the whole year, you didn’t have any issues, you hit your bonus target. If you had control issues, you didn’t hit your bonus target. I worry if you tie compensation to it that now you’re going to discourage even more so people knowing cheating is happening and not saying anything because then if they’re looking at it and saying, hey, if we get caught, we lose money, you know, we don’t get promoted. We’re not only not going to get a raise, we’re going to get maybe fined by the company. I do wonder if that’s going to make the culture even more silent, more inward looking, but I don’t have a good answer to what the other side of it should be. I don’t have a perfect solution in mind, but I am curious if you think that could possibly make it worse, maybe not even better, if it might end up being an unintended consequence of assigning it to compensation, for example.

Rob Mason: Yeah, this is a great point. I mean, I do think that there is an element of self-policing here. What we saw at the early stages of the SEC fines around that business communication being used on personal devices was that there was a feeling that it was if you saw one of your colleagues using a WhatsApp for business communication, you would be quick to pull them up on it. Now, whether or not that would be reported is a different issue. However, I think the key was that the fines were so significant, there was an element of clawback on certain individuals. So bonuses were certainly reduced that year on the basis that the organizations themselves had to pay these pretty lumpy fines. And these were $200 million dollar fines for big-ish banks. So it wasn’t sort of insignificant. It was certainly profit impacting. And so in everybody’s sort of best interests to not be in breach of those regulations and those rules, even if it was kind of somewhat more discreetly undertaken.

I mean, I guess it’s all about credible deterrent. And I think we’ve seen in other completely different enforcement outcomes, if there’s a higher penalty for wrongdoing, then you run a greater risk, and if you get caught, then you’re going to have to sort of suffer that risk.

Julie DiMauro: Yeah, I think to your point, Jack, that surveillance alone might not be the answer. People can brush up against it, they find other ways of getting around it, they sometimes can become, you know, so angered by it that it actually compels some bad behavior, which they’ve done studies on. But it’s an important component of it. And regulators are certainly expecting firms to have the technology and ability to do the surveillance that they should be doing of their workforce, of course, but at the same time, alone might not work without the disciplinary actions that Rob was just talking about, right? Compensation, clawbacks, etc., disciplining people at all levels, it seems like we need it all. So thank you both. Perfect.

Now, I just want to mention, and you both touched on it, the important role of gatekeepers, particularly at the SEC, several leaders there have mentioned the critical role that they play. In protecting retail investors and the market as a whole, Paul Munter, the acting chief accountant at the SEC, and in the past couple of years, he’s emphasized the incredibly important role that auditors, lawyers and underwriters play as gatekeepers in terms of viability and trustworthiness of the US financial system. Jack, do you think that auditors see themselves this way as essential gatekeepers? And if not, can we reframe the narrative so that they do?

Jack Castonguay: Yeah, I think they should. Put it bluntly, I’m not sure they always look at it that way. I think sometimes it’s just a focus on, hey, I’m doing a task, right? I am verifying revenue, I am confirming these accounts, and it’s just another client engagement. I think people in leadership and higher up, I do think they see themselves as gatekeepers, right? I firmly believe the leaders of the firm’s partners on engagements, they understand the risk, they understand their kind of role in not only at the company and in the financial markets, but in society as a whole, right?

Just to your point, whether it’s underwriters, lawyers, or the accountants overseeing the financial statements, at the end of the day, if you can’t trust what’s coming out of that, you can’t trust anything, right? And then prices are just spurious. So I do think that the higher up, they understand it. I think maybe as a profession, we need to do a better job explaining that to the rank and file, to your staff and your seniors. Because I think sometimes if they get disconnected, and it may be hard for them to see that they’re part of something bigger, which as we’re talking about, they certainly are. But I think sometimes that gets lost in the shuffle of the day to day, and they don’t realize what they’re doing has far broader impact in a single engagement, a single exam, right?

So I think the more emphasis we can put on the staff and the people at the lower levels, I do think that would be highly important and could maybe help move us just from a cultural standpoint, to people taking this more seriously, to understanding the ramifications. Because I do think right now that may get lost. Again, particularly for the people that are on the ground doing the work on a day to day basis.

Julie DiMauro: Perfect. Thank you. And Rob, can you tell us a little bit about how regulators are approaching the gatekeeper role in the UK?

Rob Mason: So there’s been a big focus on particularly the protection of retail investment in the UK, they released last July, so coming up for like 10 months old, consumer duty regulations, which are absolutely designed to look after the retail investor as opposed to the wholesale big banking investment fund. And I think in the same way, we’ve seen that in the US with sort of those that have abused the privilege of overseeing Ma and Pa’s pension fund are taken to the […] pretty heavily. And I think with good reason. So I think that’s part of it. Yes, absolutely agree with Jack, you know, the gatekeepers should know better.

These are people that have been in the industry a long time, they know what the regulations and rules stipulate, and they have kind of willfully intentionally breached them. And they know that that is not the right thing to do. And I think thirdly, pretty much globally, the fact that there is sort of always close to the top of the regulators priority list, is that company directors or senior executives, for that very reason, who’ve been around a long time, and should know better, have fairly significant sanctions and outcomes levied against them, and probably rightly so, mainly on that basis that they should know better.

Julie DiMauro: Terrific. I want to just tie back to or loop back to something that was mentioned earlier, culture at firms, leadership’s role in promoting a good ethical workplace, and the tone at the top that we’re always talking about and mood in the middle, whatever you want to call it, both I think are equally applicable and important. And then, you know, just even to tie in that whole aspect of, is this something we can screen for when we’re hiring people?

I’m not sure if it’s, if we’re capable of doing that, we have ethics kind of screening tests that we sometimes run applicants through, but I’m not quite sure if we can determine whether or not they’re going to cheat on an exam, but I wanted to give both of you an opportunity to talk about culture and maybe, you know, hiring practices, etc. So, Jack, can you weigh in on those?

Jack Castonguay: I’m not sure how you could screen for cheating on an exam on day one. That may be a little more difficult, but I do think if you look at what makes a good tone at the top, right, it’s management walks the walk and does the talk, right? To where they both push it on the employees, but then they show those values. So I think maybe if it’s something like, maybe early on, you need to get everyone, even if you’re in a big office like New York, right? Maybe early on with some of these exams, some of these internal training, you all take the course together, you all have the instructor go through it, and then almost like you would in college or high school, maybe you sit in a room and take the exam, right? So you see everyone doing it, you see everyone taking it at the same time, and you see from the partner down to the staff all taking it seriously.

So I think that may help on the culture side, and I think it just has to be emphasized, right? You have to sometimes hit people over the head with stuff, and this seems to be like, hey, this ethics exam, this training that you just did, this is just as important as the four hours you’re going to bill to your client this afternoon. And I think right now, it gets kind of de-emphasized, it’s just like, hey, just get it done as fast as possible so you can get back to work. So culturally, yeah, I do think you have to put more of an emphasis. And that goes back to what we were just saying a minute ago with, you know, the public trust, right? It has to be one coherent story to where we’re telling people, hey, this matters, the public really cares about this, it looks awful if we, people who are again, asking the best interest of the public, are cheating on ethics exams. So therefore, we need to do this together. And we need to put as much diligence into this, and our day to day work on the exams, on our internal trainings, on our compliance, as we do when we’re doing the audit itself.

So again, I am not sure if you can screen it on the front end. But I think from, you know, your first day, your early trainings, your two weeks of crash course training, when you start at a firm, up until you’re the partner having to do the 40 hours of CPE, and not have your secretary or your executive or CA do it, as Rob was just mentioning, I think you have to start there and just show the importance of it. And again, I think they need to see the partners doing with them, the senior managers doing it with them. And I think that would help start to shift the culture to say, hey, this is serious. Everyone from again, the office managing partner down cares about this. And that unfortunately, is not an overnight fix.

Julie DiMauro: Great ideas. Thank you. Rob, what are your thoughts?

Rob Mason: Yeah, I mean, I think looking to see if there’s better ways to supervise and oversee this type of conduct is difficult in isolation. But I think more generally, leveraging technology and monitoring of communication surveillance and like that which Global Relay offers does have a relevance for conduct or behavior. And this type of conduct is identifiable. And there can be then the respective reports of these instances that can be used as a tangible metric to both identify and measure and even compare and track instances which could feed into some sort of culture score. And that’s obviously something which is notoriously difficult to quantify in real terms.

I think harassment, bullying, prejudicial language in communications is also identifiable. And there are some concerns there which are also manageable and very important for employees who want to work for an organization that’s diverse and manages culture and respects their workforce.

For clients, they want to engage with ethical and responsible organizations. Shareholders and investors obviously favor those companies and those which respect and engage their workforce positively and potentially that has an overall positive outcome on profits and share prices.

Clearly, there’s a massive advantage for the avoidance of scandals, reputational risk, fines, sanctions, and also those remediation costs attached to any of those problems. And I guess lastly, and this sounds a little bit loose, but I’m certainly seeing the evidence that some of the clients and prospects who I engage with are being seen to do the right thing as part of a kind of corporate hygiene and looking to be better, not just in response to a requirement that the regulator tells them to do it.

I think in summary, you know, an application where you can filter some electronic and audio comms and identify and flag suspicions effectively is critical to fulfilling regulatory requirements and managing operational risk. And all of that obviously goes to preserving the reputation and share price of any institution.

Julie DiMauro: Thank you, absolutely. I mean, we have the technology to devise the lexicons to find what people are talking about, right? And what they’re sharing in terms of data.

Rob Mason: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, to a degree, there’s a fairly narrow range of language, particularly around those key elements of harassment, prejudice and bullying. And I think it’s easy to find that now there may be different risk appetites, which firms have around that. But I think that if you have financial services type scandals, then yes, that’s removable. And it’s almost kind of inherent to running a financial services business. But if you have a firm that’s branded as individuals that work there discriminate proactively against others in there. Who wants to work for them and you know, attracting and retaining hearts and minds of other employees is going to be extremely challenging. And that won’t be on the business pages of the newspapers, that’s going to be on the front pages.

Julie DiMauro: That’s right. Absolutely. Well, I just wanted to mention a couple of, you know, don’t forget items. If anything comes to mind, please supplement what I’m going to talk about, which is just whistleblower hotlines, just reminding firms that, you know, they’re a possible source of help here, when they’re well advertised, and their use is truly encouraged, when they’re consistently monitored, if anyone wants to jump in with anything else.

Rob Mason: Yeah, I’ll just add to the fact that we engage, I engage a little bit with other regulators as well as in the UK. And I think there’s a general agreement that poor conduct and behavior is rarely in isolation. And it tends to overspill into other areas where rules aren’t adhered to, because someone feels that they’re not absolutely applicable. And this has been certainly seen in conjunction with market abuse concerns. And I had that explicit conversation with the senior regulator in Europe relatively recently.

So I think the supervision of ethics will become an increasingly important theme over time. And yeah, these two sort of circles converge quite a lot. And I think it would be crystal clear to see that as we see time go by.

Jack Castonguay: Yeah, I mean, I think like in the US, we just got new audit standards on risk assessment of our clients within the past few years, some new regulatory scrutiny of them. And this is just a general risk assessment, right? To your point, when this happens, it doesn’t make the back page of the Wall Street Journal, it’s the front page of almost every newspaper, right, not just the business section. And if you realize the risk of you cheating means your firm’s going to be on the front page of the journal or The Times, and that it’s going to cost them a massive scandal, you’re going to have clients that are now going to be questioning whether they want to use you, whether they can trust you. And if you think about it from that standpoint, it’s just not worth it. Right. So if we’re supposed to be auditors, and we’re supposed to be honestly, some of the best people at assessing risk of our clients, we need to do a better job of assessing risk of ourselves. Because it’s just not worth it at the end of the day. And the more we focus on that and take that bigger picture view, I think the better off we’re going to be and our clients are going to be too.

Julie DiMauro: Wonderful. A huge thank you to my terrific podcast guests today, Rob Mason, Director of Regulatory Intelligence at Global Relay, and Jack Castonguay, CPA and Professor of Accounting at Hofstra University in New York. Please remember to check GRIP out every day at grip.globalrelay.com. Follow us on LinkedIn and stay tuned for future podcasts on a wide array of regulatory compliance topics. Have a great day, everyone.