In an article in the Harvard Business Journal entitled How ‘Carewashing’ Alienates Employees, three authors argue that some businesses are engaging in a new kind of exaggerative marketing to their employees and prospective employees.

The authors say: “Too many organizations with unsustainable ‘work hard, play hard’ cultures believe that checking the wellbeing box by offering mindfulness training or yoga classes qualifies them as having a positive and safe culture when, in fact, they’re merely ‘carewashing’.”

The term carewashing is derived from whitewashing: covering up or putting a misleading spin on a failure to meet some commitment, stated claim, or standard.

The authors argue that organizations that claim to have a caring culture must align rhetoric with reality “to avoid both external reputational risk and internal operational hurdles” – with such risks and hurdles being innovation stagnation, compromised psychological safety and a negative emotional climate.

Those unfortunate workplace atmospheres lead to employee departures, they say, “and those who remain are disengaged and unmotivated, giving rise to absenteeism and presenteeism rather than real engagement.”

A falsely positive brand

Carewashing can be used to create a falsely positive brand for the employer deliberately, or it can just be the result of tone-deaf leaders.

The tone-deaf executive is the one who hires a consultant to conduct a well-being workshop for their team, but still expects those attending to be as productive as they would have been had they not been in the three-hour workshop. The leader knows or should know the employees will have to spend after-hours time to get the work done – especially if a deadline is truly facing them early the next work day – and should see that this conflicts with the message of the workshop.

Some businesses engage in carewashing in the very language they use to attract new job candidates to their business. “We have very flexible work hours!” The business might proclaim. If this turns out to be untrue in practice, they could not only lose talented employees, but their reputation could be sullied as word gets out that the business is disingenuous about such policies.

Why should leaders care about the latest washing?

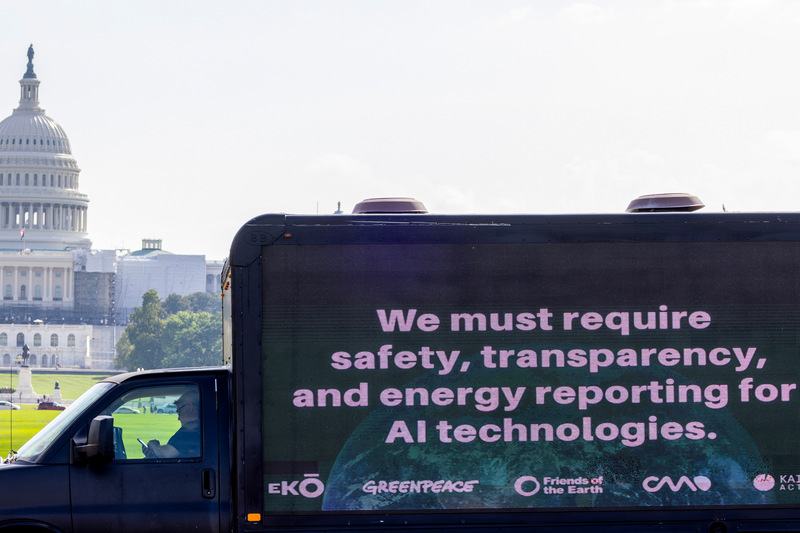

I asked one of the authors about the article and her thoughts on why companies should care about this right now. We hear about companies being fined for greenwashing and AI washing, but before any real investigations or fines kick in, why prioritize this issue?

Debra Sabatini Hennelly, the founder and president of executive and board advisory firm Resiliti, was ready for my question.

“There actually is proposed and even enacted legislation in some countries (and in states like California and Massachusetts) that touch on this issue, although they don’t call it carewashing,” she said.

“[Generation Z] cares deeply about a company’s values, perhaps even more than the product or service it provides.”

Debra Sabatini Hennelly, founder and president, Resiliti

And it has been used and directly relates in the corporate social responsibility context to supply-chain issues such as modern slavery and child labor, she said. “That’s when you say you don’t tolerate these things in your supply chain or proclaim that you expect suppliers to meet your code of conduct – but then you don’t actually ask the suppliers about it or audit them for such behavior,” she explained.

I asked Sabatini Hennelly about the Gallup surveys quoted in her co-authored article.

The article had noted that a 2024 Gallup survey indicated that the percentage of employees who strongly agree with the statement that their organization cares about their overall wellbeing has plunged to 49% in 2020 to 21% in 2024. And another Gallup survey had shown that improving wellbeing and culture rated much higher than increasing compensation among the things “quiet quitters” would like to change about their work.

I asked her whether she thinks a new generation of workers will fill the ranks of leadership and focus more on mental and physical wellbeing, improving workplaces for everyone?

She said job applicants can do a deeper dive on prospective employers using social media and she does suspect they will bring a new value system into the workplaces they lead.

Gen Z – or those born between 1997 and 2012 – will surpass the number of baby boomers in the workforce this year. “This generation cares deeply about a company’s values, perhaps even more than the product or service it provides,” she said.

Indeed, a survey conducted by Network of Women and Deloitte said that “Gen-Z no longer forms opinions of a company solely based on the quality of their products/services – but on their ethics, practices and social impact.”

Skeptical about ‘ethical’

New research suggests that companies that use words such as ‘ethical’ in annual 10-K filings are associated with a variety of negative financial outcomes.

Use of the words in annual statements was correlated with a decreased interest in the stock of the company in question, the study found. In the first 48 hours after earnings were announced, stock prices increased on average about 1.15% for companies that didn’t use the words in their report, whereas stocks of companies that did use them increased only about 0.11% in that two-day period.

Basing their findings on 21 words that seek to evoke a sense of trustworthiness, the authors also found that companies whose annual filings included the words tended to pay about $100,000 more in auditing fees than firms eschewing the words – the higher auditing fees at least suggesting more risk was spotted.

Have the wisdom and humility to admit you don’t have all the answers when it comes to wellbeing at work.

And the SEC is wary of statements to the effect of “trust us – we’re so ethical,” with companies using trust words being 15% more likely to receive a comment letter from the agency asking them to clarify information on their annual reports than companies that did not use such trust words.

Wall Street’s top regulator likely sees its scrutiny as an extension of its disdain for practices that suggest deceptive or misleading marketing practices by US investment funds and other firms.

“Companies likely use trust words to project a positive image and better manage information within the annual report, but it seems that no one is really fooled,” says Gopal Krishnan, a professor of accounting at Bentley University in Waltham, Mass., and one of the study’s co-authors.

The authors used a computer program to search for the 21 words in the annual filings of 3,595 companies between 1995 and 2018. In their sample, 1,659 firms used trust words and 1,936 didn’t.

Advice for business leaders

The authors have some advice for business leaders, so they can avoid uninvited scrutiny and develop true (and not just token words of) trust in their organizations include:

- Conduct regular organization-wide (anonymous) assessments that get to the root of the desired culture of caring, using scientifically validated measures to ensure the results are accurate, reliable, credible, and ethical.

- Screen for people-based values and competencies (empathy, listening skills, openness to others, caring) and ethical behavior in hiring and promoting.

- Evaluate performance based on criteria that go beyond superficial, short-term results.

- Have the wisdom and humility to admit you don’t have all the answers when it comes to wellbeing at work.