This is a transcript of the podcast Duane Pozza on the Chevron Doctrine between lawyer Duane Pozza and GRIP Senior Reporter Carmen Cracknell.

[INTRO]

Carmen Cracknell: So thanks for joining us again, Duane. It’s great to have you back. Hopefully you were happy with the last podcast we did. For anyone listening who didn’t listen to that, could you reintroduce yourself, please?

Duane Pozza: Sure. And thanks for having me back. I’m Duane Pozza. I’m a partner at Wiley, a law firm in DC and co-chair of the Privacy, Cyber and Data Governance Practice.

Carmen Cracknell: So could you give us some background on the Chevron doctrine and why it came up in the news last month?

Duane Pozza: Sure. So Chevron is a case from 1984, a US Supreme Court case, Chevron versus Natural Resources Defense Council. And the holding of the case essentially was to instruct courts to defer to federal agencies reasonable interpretation of a statutory provision that was ambiguous.

So to unpack that a little, federal agencies typically operate according to and also interpret lots of different federal statutes. Sometimes those statutes are clear about what has to happen.

And in many cases, the agencies have to determine if there’s some ambiguity as to whether or not they can act in a certain way or how they should act.

Chevron had said that when there are multiple reasonable readings of a statute, there is essentially a policy choice for the agency to make and the courts would defer to that. So over the last 40 years, it’s come under criticism, certainly from many folks in industry and others who think that, who had issues with it, including that sometimes it would lead to shifts in policy over time.

So in a case called Loper Bright Enterprises versus Raimondo, which was decided about a month ago by the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court overruled the Chevron doctrine under this case. So Loper Bright concerned a rule that was about fishermen.

The National Marine Fisheries Service required fishermen to fund certain at sea monitoring programs and that was challenged in the Loper Bright and they argued that the statute didn’t authorize it. So in the Loper Bright decision, the Supreme Court essentially agreed with that.

They overruled Chevron and they held that instead of this deference, courts that face some uncertainty about how to interpret a statute don’t defer to an agency’s reading and instead courts will actually examine the original language of the statute and exercise their own independent judgment as to the best reading of the text.

So the short version is it moves from the Chevron doctrine world of deferring to what an agency thinks, sort of ambiguous parts of a statute mean to courts deciding it directly and that means also litigants getting, I would say, another shot in court to determine, you know, the challenge of an agency got it wrong.

Carmen Cracknell: Okay, if it all depended on a statute being unclear or silent on an issue, is there a way for Congress to get around this problem?

Duane Pozza: Yeah, that’s a great question. So I’ll start by saying that there’s a lot of sort of doctrine that is unclear post-Loper Bright that will have to be sorted out, including how much Congress can specifically address it.

But I do think that there are specific kinds of things that Congress could do under, say, new statutes or if they’re amending statutes because this is basically about how you interpret a statute, Congress could be, you know, very clear about certain things that they want done under a statute. There’s also the possibility that Congress could be clear when they want an agency to make a decision.

So you know, a lot of litigation under Chevron is around areas where people call them, you know, like gaps in the statute that an agency is trying to fill. But Congress could, you know, direct an agency to, you know, fill up the details of certain statutes to define certain kinds of concepts.

So I think that there will be, you know, further cases about what the limits are in terms of how much Congress can direct agencies to do it. But certainly you could see Congress in the statutes providing sort of specific guidance to agencies. And a lot of the litigation actually will be about some of these older statutes that are less clear, actually.

Carmen Cracknell: So the Supreme Court said, have they said former decisions using Chevron will still stand?

Duane Pozza: Yeah, I mean, I think this is also also falls a little bit in the category of we’ll see what happens next. But the Supreme Court did write in Loper Bright that the decision does not call into question the lawfulness of specific agency actions that were previously upheld under Chevron.

The court explained they’re still subject to what they call stare decisis, which is essentially sort of a broad way of saying respect for precedent, despite changes in the methodology of interpreting it. So I think that we’ll see existing decisions that were decided under Chevron still challenged, but we’ll have to see whether or not the previous interpretation still stand.

I will say it’s certainly not automatic that they’ll be revisited. That much is clear from Loper Bright. But you can see, for example, that if one court held something under Chevron and then another court that’s not bound by it is interpreting it for the first time, well, then maybe they don’t necessarily have to defer to the other court’s judgment.

It’s kind of situations like that on a case-by-case basis, where I think you’ll see more challenges. And to the extent that there are some old decisions being revisited, I think it’s really going to get into the weeds of the different kinds of what they call the stare decisis factors.

Carmen Cracknell: So what do you think we can now expect to see from US agencies in giving their interpretations of statutes?

Duane Pozza: Yeah, so I would say that many agencies, including the Federal Trade Commission, which I follow extensively, had kind of pulled back from relying on Chevron deference as a way to justify their readings of statutes and have really emphasized that they’re interpreting the text and finding supporting evidence that goes along with whatever rule they’re going to make.

I would say not all of them, some agencies, especially with really broad statutes, still have been relying on the Chevron approach. But I think now agencies will have to really drill down on what’s specifically in the text and justify it, their interpretation. I would expect that work to be done upfront much more.

That is, you’ll see agencies seeking comment on it, and when they announce rules, they’ll have to explain why they think this is the best interpretation of the statute, and then they’ll have to be prepared for potential litigation. So I think it will change the way that agencies approach some of these rules, and we’ll just have to see. I certainly don’t think that it completely hobbles agencies from acting pursuant to the statute.

That is, there’s still many statutes and many regulations under those statutes that agencies will continue to pursue. I think that they will just have to explain and defend them on potentially different grounds than they would under Chevron deference.

Carmen Cracknell: So how will this affect federal rulemaking, do you think?

Duane Pozza: Yeah, it’s interesting. It depends a lot on the sector, and it depends a lot on the statute. I think there are, in many different sectors, there are sort of older, broader statutes where you’ll see more challenges as to what an agency can do. And then sometimes some of these newer statutes are much more explicit and direct, and there’s less room for a challenge.

One area I look at a lot is the technology sector. And Chevron being overruled could be particularly significant for the technology sector, because there’s so much rapid innovation occurring. But many of the statutes that agencies have looked to to approach it are very old and not very specific. So it’s just one example.

The FTC, which generally has authority over unfair and deceptive practices in the marketplace or large swaths of the marketplace, enforces a statute that dates back to 1914. And it has very broad language. So I think that the FTC has sought to use that broad language to approach things like AI that are developing in the marketplace.

And there’s sort of an enforcement aspect of this, but to the extent that the FTC is focused on making broad rules about AI or privacy or data security, they’re going to run into this concern that perhaps they’re stretching some of their statutory authority too far or that it doesn’t authorize them to put in place if they go down the road of very specific rules about AI or privacy or data security.

So that’s one area that I’m keeping an eye on is what does this mean for the ability to regulate new technologies under old statutes?

Carmen Cracknell: And besides AI, because we focus a lot on financial services, what about for that sector? What does it mean, do you think?

Duane Pozza: Yeah. So financial services is interesting because this is an area where there are a ton of statutes and additional regulations. And I think it really is going to require a case by case approach to look at the basis of specific regulations under specific statutes. And to put a finer gloss on that, these kinds of challenges can arise in a couple of different ways.

One is you might see more litigation. I mean, you already are seeing a lot of litigation in the US around new sort of financial regulations at the time they’re adopted on the theory they exceed the agency’s authority. So I think you’ll continue to see that. And these kind of Loper Bright arguments will be part of challenges to new regulations, in addition to arguments about the evidence and the cost-benefit analysis.

The second piece, though, is when agencies are interpreting old rules in enforcement actions, I think you’ll see some pushback. You could see some pushback arguing that the rules themselves are invalid to the extent they’re being enforced.

Just one agency that I look at a decent amount is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the CFPB, which is primarily responsible for financial regulations around consumer protection. And there you see certainly the CFPB putting out a lot of rules and guidance that might not necessarily be always styled as a rule around what constitute unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices, or interpreting specific provisions in some of these financial regulations.

And you’ve already seen, I think, a number of legal challenges to their interpretation. And that’s an area where courts will really be drilling down on what is the actual meaning of the statute that the CFPB is interpreting? And does the court think that is the best reading of the statute, as opposed to deferring to the way the CFPB is interpreting those provisions?

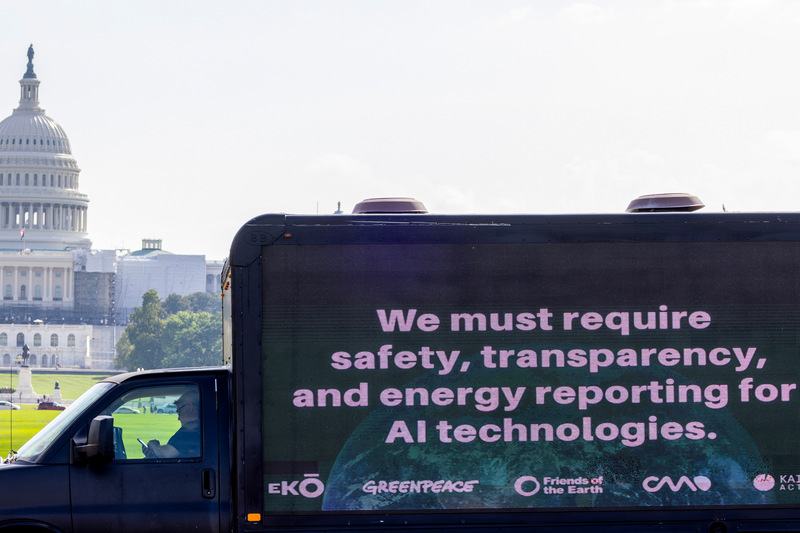

Carmen Cracknell: Great. So we focused a lot on Chevron. Just to speak more broadly, what do you see for the regulatory landscape in AI in the coming year?

Duane Pozza: I think that agencies are trying to figure out how to regulate AI within their own purview. So the federal financial regulators, for example, are seeing what authority they have around AI and financial transactions, and then approaching it using their statutes.

I think other agencies like the FTC that have a broad purview are trying to determine actually how broadly they want to, if at all, try to do rules around AI, which can apply in a lot of different contexts. I think that this gets at one of the fundamental tensions here is that original statutes, almost all of them are not written with AI in mind.

So the question will be whether or not their original statutory language gives the chance in order for a regulator to approach AI. But broadly speaking, you’ve seen a big push at the federal level to push forward with a lot of risk management principles. Those are largely have been voluntary so far.

There’s been a lot of work to develop risk management principles that industry can implement. And I think that has been adjacent to using some of these older sort of statutes or regulations to get at AI. And then an area that I’m watching, which is always an issue in the US, is that states have their own ideas about how to regulate things.

And as with privacy, states have now begun to look at, and in one case, pass specific state laws that regulate how AI is being used, which creates a risk of a Patrick approach. But that is something that I think over the next year, I’ll be watching out for. And I think companies generally should be watching out for, including in the financial services space.

Carmen Cracknell: And what about for crypto regulation?

Duane Pozza: Crypto regulation is interesting. There’s a lot of litigation going on right now that I think falls into a similar bucket to what we’ve been talking about, which is the SEC in particular, not just them, but they’re certainly on the leading edge of this, has attempted to interpret older statutes to cover digital assets and crypto, which obviously were not originally in mind when the statutes were passed.

And so you’ve seen already, and there’s a number of cases teed up that raise this issue of whether or not that’s a reasonable interpretation of some older laws.

So I think that those those battles will continue to play out in court over the next year, certainly. It’s an area where the Supreme Court has spoken. It’s a big shift in the way regulation will be approached. But I’m sure we could do this again in a year and see what the fallout is in different areas. It is dynamic. And I still think there are many questions that will be resolved in some way over the next year or so as it shakes out in courts.

Carmen Cracknell: Well, thank you so much for your time, Duane.

Duane Pozza: Sure. Great.