This is the transcript of the podcast Lukas May on carbon markets, the role of registries and developments in regulation, a discussion between GRIP’s commissioning editor Jean Hurley and Lukas May, Head of Expansion and Policy at Isometric.

[INTRO]

Jean Hurley: Hello, listeners. I’m Jean Hurley, commissioning editor at GRIP. Today on the GRIP podcast, we’re here to discuss carbon markets, the role of registries, and regulation with Lukas May, head of expansion and policy at Isometric. His previous roles include leading senior positions in the UK government, UK Fintech-Wise, and at the UK financial services regulator, the FCA, where he led the creation of the Innovation Hub.

Hello, Lukas. Welcome to the GRIP podcast. Can you please tell us about yourself and what you do at Isometric?

Lukas May: Hi, Jean. Great to see you again. Absolutely. So I lead the commercial and policy teams here at Isometric. Isometric is a carbon removal registry. So it’s our job to verify the activities of companies that are taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, and then we issue credits onto our registry.

Jean Hurley: Thank you. So like other companies, financial services firms will also be expected to reach net zero by 2050. Can you please explain how firms can achieve this through offsetting and voluntary carbon markets?

Lukas May: Certainly. So carbon removal is the net in net zero. You decarbonize as much as you can. All your energy goes renewable. You cut back on non-essential travel. Your airline starts using sustainable aviation fuel. But at the end of the day, you will still have some emissions. And so it’s those residual emissions that you need to neutralize with carbon removal if you want to be net zero. And everyone who’s looked at this seriously, the US government, University of Oxford, the UN’s IPCC, every major study report is clear that there is a critical need for carbon removal to happen and to happen at a huge scale.

We need to be taking billions of tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere every year by 2050. And that is thousands of times bigger than the industry is today. So there’s a huge challenge and a huge opportunity.

Jean Hurley: So currently offsetting is voluntary. What are the commercial considerations and motivations for firms?

Lukas May: Right, it’s a weird situation. So, I mean, I come from a financial services background and worked in the regulator, spent a lot of time on regulation. It’s bizarre to me to think you could have a world where some banks are regulated and others are unregulated and consumers just choose between them.

If banking is too important to leave unregulated, which it is and things blow up if you do that, the same could be said for carbon removal. It’s just too important to the planet to have a Wild West in this market. But yes, today it is mostly unregulated in terms of both the quality of what firms are packaging up and selling as credits, but also in terms of what is requiring companies to actually invest and buy these credits.

In most cases, they’re not forced to buy credits at all. And if they are, they’re not forced to buy particularly high quality types of removal credits. And so that means for a lot of companies, they’ll just buy the cheapest option on the market. And that has created a big problem because years down the line, journalists have started to expose some of these low quality projects as being not very effective at helping the climate in the way they said they would.

And so back to your question, what are the commercial motivations to buy credits today if regulators aren’t forcing you to? Number one, marketing. You might wanna brand your coffee as kind of carbon neutral coffee, and a lot of people do do that.

Secondly, you might have investor pressure, activist investors who want to see that you’re doing your bit for the planet and the community. So buying carbon credits might be part of your ESG strategy.

Employee talent management, it’s very simple. Today, top talents want to feel like they’re making a difference. And so this can be a way that corporates within an industry, banking, consulting, tech, can differentiate from their competitors in the war on talent. And then there are actual commercial motivations as well, like direct commercial benefits for some industries. So if you think about banks, buying credits is something that they can then offer as a value added service to some of their clients. They can kind of resell those credits. They can act as a sort of single broker, obtain high quality credits, and then resell them to clients as a service. And several banks are getting into the space to do exactly that.

Within the people who are buying credits today, there are some who are prioritizing high quality and pay a premium to do so. And I think the main motivations there are, frankly, corporate philanthropy, so deep pocketed institutions with people running them who genuinely care about the climate crisis. Think Bill Gates and Microsoft, for example. They’ve committed to be carbon negative. They’re not just buying the cheapest credits to get them there because they really want to have an impact.

And then reputational risk aversion is like a really key driver for buyers towards quality. If you don’t want to be in The Guardian for greenwashing, then you will naturally have to gravitate towards the less risky, more reliable, more expensive end of the market. And then finally, although there’s not much regulation today, a lot of companies are anticipating future regulation. So if you expect you’re going to be forced at some point to buy these credits at scale, you might want to start buying now, firstly to help build an industry so that there is meaningful supply when you really need it, and the cost hopefully comes down by that point. And secondly, to get the experience and learnings that you need so that you can comply with regulations in time when they come in.

Jean Hurley: Yeah. So there’s different types of credits: I was reading there’s removal-based credits and avoidance-based credits. Can you explain the differences for our listeners, please?

Lukas May: Yeah, definitely. I mean, one of the big problems and sources of confusion in the market is that a lot of what has been sold under this umbrella term as offsets isn’t actually carbon removal. Most of the credits that have been sold to date have been avoidance credits. And so removal very simply is taking CO2 out of the atmosphere and then storing it permanently somewhere. It’s negative emissions.

Avoidance, on the other hand, isn’t cooling the planet down. It’s not taking CO2 out of the atmosphere. It’s preventing more CO2 from being released. And so avoidance done well is actually really important. We definitely want to stop releasing CO2 wherever we can. But it shouldn’t really be claimed to offset your emissions because by definition, you won’t then reach net zero. It’s not contributing negative emissions to your total calculation. And so you then kind of have this also inherent quality problem with some of these types of avoidance credits.

Take, for example, avoided deforestation, often referred to in the industry as red, is paying someone to not cut down trees. The whole basis of that credit is imagining the world in which you didn’t make the payment and saying: “How many trees would have been cut down?”

You really can’t prove that. It’s an unverifiable counterfactual. And an unregulated market, it’s no surprise that this type of credit has ended up being, well, many credits have been issued under this category that probably should not have been issued.

There are over a billion credits in the carbon markets that have been issued to date. Most of that has been avoidance, and most of the avoidance credits have been avoided deforestation. And unfortunately, a large proportion of them have been shown to have been inflated. Intuitively, we kind of know this. If there had been a billion tons of avoided carbon emissions, that’s really significant. Global annual emissions are around 30 to 40 billion. This would be showing up in the data. It’d be a well-known success story. And unfortunately, that’s not the case.

And so, yeah, this is a challenge, particularly where the bodies who are tasked with verifying this activity have conflicts of interest.

Jean Hurley: Thank you. I mean, I think I’ve read an article in the FT about that, where it was saying in Brazil, they found some fraud where people have been selling carbon credits from stolen land even. So quite shocking, isn’t it? Thank you for explaining about the quality of credits.

How are you and isometric hoping to improve on the standards and the inconsistency around carbon credits?

Lukas May: That’s actually exactly what isometric was founded to do, which was to try and address this quality issue and restore trust to carbon markets. And ultimately, we need the trust in carbon markets. Otherwise, we can’t scale the carbon removal industry to the level that the planet needs. And so carbon credit programs, also known as registries, these organizations like Isometric, in the absence of regulation, we’re the ones who are overseeing what is going on in the industry, judging basically whether or not credit should be issued for the activities that project developers are carrying out.

I think the main problem is registries haven’t done this job effectively in the past. And so we looked at that and we saw three critical areas we thought we could do better, and that frankly, we need registries to be better at. And hopefully in time, regulation will be a forcing mechanism for this, but in the meantime, we’re trying to set an example. So firstly, scientific rigor. Linking back to the earlier point about avoided deforestation credits, trying to prove a counterfactual that you can’t really verify one way or another. That’s why we’re exclusively focused on carbon removals.

We only want to issue credits where we have solid scientifically robust proof that one net ton of CO2 has been removed from the atmosphere. And so we’ve invested deeply in building our scientific expertise. Half of the company are top scientists in their fields, recruited from a range of academic institutions around the world. They’re the ones who write our rules for carbon removal, what we call protocols. And then carbon removal companies have to follow those rules. We then check that they followed the rules before we issue the credits.

So firstly, scientific rigor. Secondly, reducing conflicts of interest. And I think most importantly here, unlike the traditional registry business model, we don’t get paid by suppliers. So those people whose homework we’re meant to be checking shouldn’t be the ones paying us. That just seems an obvious conflict in an unregulated market. So we get paid by buyers, not suppliers, and we charge a fixed fee, independent of how many credits we ultimately issue. So we’re not being paid per credit, which is another feature of the traditional model that creates incentives for over-crediting.

Finally, transparency. A carbon credit is just the outcome of a mathematical equation. You don’t receive an Amazon package with your carbon removal in it. There’s nothing physical. It’s the total number of tons of carbon removed from the atmosphere minus the amount of carbon you emitted to make that happen. And both sides of that equation are critical. And in the past, registries have not been very transparent, especially about the deduction part.

So the calculation of emissions, also known as a life cycle assessment, LCA. Where they have shared information on this, it’s often buried in 300-page PDFs and nobody can find it. We’ve invested really heavily on the tech side of our registry to make it user-friendly. And more importantly, to include every single element of the calculations we use. This is all the way down to the amount of diesel used by a truck, delivering materials to a factory based on how many miles the truck drove to get there and all the evidence we collected to evidence that. And this is a radical new level of transparency for the industry, but we think it’s critical to building trust.

Jean Hurley: So I think at this stage it would be useful for the listeners if we define some terms. I think you’re going to look at standards, protocols and methodology.

Lukas May: These are terms that I think we all, even those in the industry, are using somewhat inconsistently. So I think really good, really good moments to define them. So the common usage of methodology and protocol is that they are basically synonyms, they’re interchangeable. We call them protocols. So a protocol is basically the recipe for cooking carbon removal. Registries write these protocols or methodologies. Carbon removal companies have to follow them. If they follow them properly, they can get credits.

There is a bit of a nuance to this. Protocols are generally considered to be more prescriptive and more detailed than methodologies. And that’s why we refer to ours as protocols, but for everyday usage, they’re the same thing.

Standards, which is another word that gets bandied around a lot in carbon markets, it really depends on the context. So people sometimes use the word standard to mean registry. So people would say Isometric is a standard or Isometric is a registry. And that’s because registries often have an overarching document like a constitution.

We have one called the Isometric standard and that sets the overarching rules that all of the underlying protocols have to comply with. So for example, our standard says we will only issue credits for removals, not avoidance activities. And then all of our protocols are protocols related to carbon removal.

The other way people refer to standards, more the kind of plain English sense of the word, is just any set of rules. So because there isn’t formal regulation, there’s kind of a patchwork of different things going on in the carbon markets. There are accreditation bodies, folks like ICVCM (the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market), ICROA (the International Carbon Reduction and Offset Alliance). These are sometimes referred to as standards. The work that is starting to be carried out by government is often referred to as standard setting. It’s essentially just the general collective of written rules, guidance and regulations that govern carbon markets.

Jean Hurley: You once said you can’t rely on good actors doing good things forever. How can firms be incentivized to do the right thing in the absence of government setting regulation?

Lukas May: I think there are the self-interest points I alluded to earlier that are starting to change the behavior. In particular, reputational risks we see are driving a lot of activity, especially as a lot of the scandals have kind of emerged over the last year or two. And that means that buyers are starting to care more about quality. And if they care more about quality, then that can create incentives for firms in this space to do the right thing.

But generally I do believe regulation is crucial here. And fortunately, we are starting to see that emerge. So the EU is furthest ahead. They drafted a piece of legislation that sets out a regulatory framework for carbon removals. It’s called the CRCF (Carbon Removal Certification Framework). They’ve actually already passed the legislation and are now shifting into the implementation phase, where the detailed underpinning rules for particular carbon removal methods are being consulted on.

And I think the hope is that these methodologies can set a floor on quality, because what we need to do is prevent the race to the bottom dynamics that can otherwise emerge, where companies are incentivized to cut corners, to save costs. Nobody’s really saying you need to buy the higher quality thing. And so money flows to the lower quality cheaper products, and then you have this very damaging race to the bottom.

The carbon removal industry is quite new. It hasn’t been kind of tarnished by scandals in the way that the more traditional avoidance market already has been. So there’s an opportunity to get this right. We need all the actors in the space to really do the right thing, but we can’t rely on that forever. So the regulation needs to come in sooner rather than later to make sure we get this right.

Jean Hurley: So Isometric are developing their own protocols. How did you do this?

Lukas May: Yeah, so as I mentioned earlier, we’ve hired a lot of top scientists in each pathway that we cover. They bring the academic expertise, but then we work really closely with industry. The company’s actually putting spades in the ground, building factories, crushing up rocks, whether it’s direct air capture, enhanced rock weathering, ocean alkalinity enhancement. fields that are not just academic. You need to have the real world know how. And so we draft protocols in collaboration with companies in the relevant sector.

We kind of synthesize the science and the practical know how into a draft protocol. And then we have almost like a peer review process. We have established something called the Science Network, which is a group of 200 plus independent scientists who spend time in academia, but they’ve agreed to carry out these reviews and give feedback on these draft protocols when we create them. And so that’s a really valuable process for sharpening and improving the draft protocols. And then after we’ve gone through that process, we’ve run a public consultation. So a bit like a government or a regulator. Anyone can then comment at that point. We have to incorporate the feedback that we receive. And then finally, we have a final version of the protocol ready for use.

Jean Hurley: And so you’re working with standard setters as well?

Lukas May: Yeah, that’s right. So we actually have our approval from ICROA, which is one of these accreditation bodies that I mentioned in the carbon markets. They look at things like your governance procedures, the types of processes that you follow when you’re writing your protocols, but also when you’re issuing credits. And so these are voluntary industry bodies. ICVCM is another one like that. CORSIA is a bit different. It’s actually a UN backed scheme airlines that is closer to a kind of mandatory program. So if your home country has signed up to the relevant UN treaty, then you as an airline are on the hook for buying credits to offset some of your emissions and you have to buy them through the CORSIA scheme. And the CORSIA scheme provides approval for the registries like Isometric who issue the credits within that scheme. And so yeah, we’re applying for the CORSIA approval at the moment.

Jean Hurley: Going forward, what do you think is the role of governments?

Lukas May: I think the critical thing is they set a minimum bar on quality. And so CORSIA, which I just mentioned, for example, has been criticized actually as being too permissive. Some of the same types of avoided deforestation credits that have been subject to the various Guardian exposés have been eligible in the past for CORSIA, but it can ramp up those standards over time. And the EU provides an example of this. The CRCF legislation that they brought in set some very clear minimum quality standards. For example, 200 years or more durability, removal credits only, not avoidance credits. And governments have a natural role to play in making some of those tough decisions and just making sure that there is a clear definition of what is good enough to be a carbon credit.

And then I think once governments have fixed that, they define what is a good carbon credit, you then wanna make sure that there’s very clear guidance on how those carbon credits should be used. So the emissions trading scheme (ETS), for example, in the UK and in the EU is a natural opportunity. If you’ve defined what a good carbon credit looks like, then you can potentially introduce that into the ETS, which is this cap and trade system for emissions, where polluting industries have a certain cap on how much they can emit. And they can buy allowances from other polluting companies that aren’t using all of their allowances. But a very natural way that could evolve over time is to allow carbon credits to be purchased under those schemes, because they are negative emissions.

So they are a way for those polluting industries to meet the caps that are set for them under these schemes. So once you’ve defined quality, you have all of these opportunities that open up for other policy measures, all of which in the end can contribute to investment and growing the market for carbon removal overall.

Jean Hurley: So we’ve talked about regulation in the EU and also what they started to do in the UK as well. How about in North America?

Lukas May: Yeah, so I think just to briefly expand on the UK, the interesting thing is they have an equivalent of the EU CRCF yet.

So they don’t have this set of rules that defines what a good carbon credit looks like, but they need it. And the reason they need it is because they have gone further than the EU in another policy area, which is the one I just referred to, integrating carbon credits into the ETS, into the cap and trade system. You can’t plug carbon credits into any cap and trade system today, because so many credits are under priced and are basically junk. So that kind of $10 per credit, for example, that would totally crash a cap and trade system where the price from carbon is currently around $100.

So the UK has already said that they plan to integrate carbon credits into the ETS. That won’t happen until 2028, but between now and 2028, the UK is going to have to write some kind of equivalent to CRCF to define what good looks like for carbon credits.

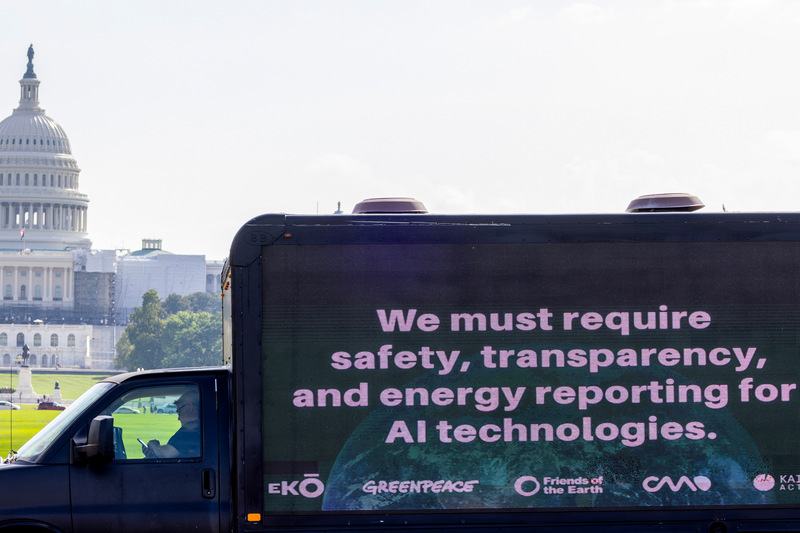

So that’s very interesting development in the UK. And then in the US, there is not a kind of federal level set of regulatory standards being developed. There just isn’t the political appetite or capacity for Congress to pass legislation on this.

So they’re doing the next best thing actually, which is the Department of Energy is buying carbon credits directly. They’re buying carbon removal credits. They’ve set aside some money to do that, but more importantly, they’re making really detailed, transparent decisions about what they’ve chosen and why. And by publishing their homework on those decisions, it will set a kind of de facto series of regulatory guidance for companies in the US to say, okay, this is what the US government looks at when it buys carbon credits. And they’re encouraging actively the private sector to follow suit. So for example, Google have already announced that they’re going to match the funding that the Department of Energy is spending on carbon removal credits.

Jean Hurley: Thank you. So we’ve discussed the integrity of the market and then durability challenges associated with credits. What about greenwashing and misleading advertisements? And do you have any examples that you could share with our listeners?

Lukas May: Yeah, that’s a great question. I think the classic example on greenwashing and maybe misuse of carbon credits is offsetting your flight. It’s very cheap to offset a flight. You pay five bucks, 10 bucks, take your flight with a clean conscience.

It’s very compelling for the customer. But if you actually look into the projects that you’re funding, they are generally this low quality avoidance credit type. And so you may just be basically throwing money down the drain. And the problem is if you were to try and offset your flight with high quality carbon removals, it’s just too expensive. Customers aren’t going to be willing to spend $100, $200 to offset their flight. And so that’s a bit misleading, I think. And it’s quite a common practice still today amongst the airlines.

The Green Claims Directive in Europe is actually likely to have a really big impact on what happens in this space. So they are effectively banning companies from saying that they are carbon neutral or that their products are carbon neutral or carbon negative. And we’re already starting to see those phrases come off of labels of everyday products, whether it’s kind of oat milk or craft beer.

Marketing those products as being, yeah, carbon neutral is gonna become a lot harder. And basically what the EU is saying is you can’t substantiate that claim by buying junk credits that don’t do anything.

And the interesting thing there is, in parallel, the CRCF is coming into force. And so although they haven’t explicitly joined up those two pieces of legislation yet, the very natural assumption is that once you have EU approved credits, there should be a path to making some of these claims again without the risk of greenwashing, because you can only make the claim if you purchase these high quality EU-endorsed credits.

So yeah, that’s a really interesting development happening in Europe.

Jean Hurley: I mean, I was just wondering with all the funds naming rules that they’ve got coming out, what you can say both in the UK and the EU, once they’ve got that in place, do you think then it’ll be easier than to transfer that to carbon credits?

Lukas May: Yeah, I think there’s definitely an interesting read across. I don’t think the folks in the environment ministry who are working on the carbon markets legislation are trying to join up with what’s going on in that area. But yeah, I think that would be a natural thing for them to be looking at.

Jean Hurley: So looking to the future, how do you envisage governments and perhaps registries such as yourself working together?

Lukas May: Governments should be setting the regulatory frameworks. Registries would actually be a regulated entity within that framework and they are within CRCF. So they’re defined as certification schemes and we and other registries will have to apply to Brussels to get a license because they play a critical infrastructure role. And so we will be working together in the sense of we will be regulated directly by governments and having to follow a set of rules that they’ve established.

I think that’s the primary way in which we would collaborate. And then I think there’s, particularly in this phase where governments are still figuring out how it should all operate, there’s a sort of shared learning. Registries have been filling the regulatory vacuum and de facto enforcing the kind of rules within the markets. So there’s a lot that we can and we are sharing with governments as they write their own rule book at the moment.

Jean Hurley: Thank you. So Lukas, what do you think is next for you in Isometric? How do you see yourselves maybe in 10 years down the line?

Lukas May: Yeah, it’s fun to think about. I think I would characterize last year as us going from zero to one. So we had talked a good game about how we were gonna be different. We’d hired all the scientists, we’d written some rules. But last year we really actually put that into practice for the first time and we verified a project and issued some credits onto our registry.

This year it’s all about going from one to a hundred. So we brought on some of the world’s top buyers. We’ve recently issued credits, for example, to JP Morgan. That’s really a scaling challenge and opportunity for us. We need to be able to meet the high expectations these buyers have. I’m excited over the next year, five years, 10 years, for the progression of the industry to the kind of level of maturity and scale that it needs to be at. And we’re starting to see this next wave of buyers coming in. Currently buyers are very big companies, very motivated on climate grounds. But as I mentioned earlier, we’re starting to see more commercially motivated purchases of carbon credits, regulation is starting to drive a much broader set of companies into the space. And so this is essential to the industry scaling up and we need to be able to scale up to meet that challenge and opportunity as well.

So that’s what the planet needs is the carbon removal industry to win back trust, to get to the billion tons of carbon removal a year scale. And yeah, that’s what gets me up in the morning. So I’m excited for that.

Jean Hurley: Lukas, thank you for your time and sharing your insight on carbon markets and thanks to our listeners for tuning in.