The presentations during the conference, with the exception of the keynote speeches, were covered by Chatham House rules, designed to ensure that the presenters felt comfortable to talk openly to those gathered.

In the spirit of those rules we have drawn together some of the most interesting, but unattributed speaker commentary and organized it into three key themes: capital and capital markets; geopolitics as well as regulation, regulators and risk. In this first article of the series we look at some of the issues discussed by speakers in connection with capital and capital markets.

As the name of the conference suggested, a key theme that many of the discussions at least touched on was capital and the capital markets.

Almost all speakers argued for the urgent need to encourage capital formation in order to permit global economies, and human society more broadly, to deal with key challenges including the massive demographic shift to aging populations and the many problems resulting from climate change that governments around the world are already grappling with.

Estimates of the capital required in order to ensure the decarbonisation of economies were in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Many speakers suggested that deeper liquidity pools are required and that this need is being driven by investment needs stemming not only from demographics but also from:

- decarbonization;

- infrastructure;

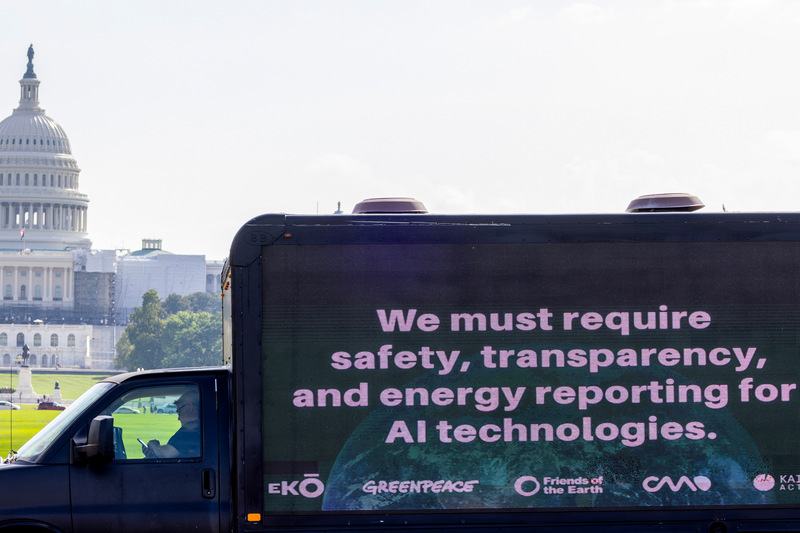

- AI; and

- technological change more generally.

It was considered unlikely that all of these capital-intensive endeavours can be financed by governments or even public markets, given their available combined strength. In this context it is, of course, important to remember that there are real concerns about government debt levels in the US and around the world.

Speakers felt vibrant and efficient private capital markets are needed in order to meet the demand and allow the global economy to tackle some of these challenges. Coupled with interest rates that are unlikely to return to the unprecedented lows seen prior to the pandemic, this means that we may be seeing the emergence of a new capital and investment super-cycle.

One of the speakers asserted that it was institutional and regulatory changes (pushing capital into investments guaranteeing short-term liquidity where this was not necessarily needed) that have led to the reduction of capital availability from pensions funds more broadly. An interesting example of the potential of uintended consequences of well-meaning regulatory intervention or rule-making. Overly ambitious regulation was also cited as one of the reasons why capital is moving away from banks and public capital markets to private markets.

The very definition of private markets / private capital was challenged with one speaker making a crucial point about the need to differentiate between the various assets lumped together in this category and, particularly from a regulatory perspective, to focus on the characteristics of these investments.

Should these be rules either be reversed or relaxed in the future, it could well release capital and lead to more IPOs resulting in more vigorous markets and better capital formation. There is no doubt, given the tenor of messaging from the UK’s government, that options on how to do this are already being examined.

Some of the speakers either said or implied directly that markets are not as “open” as they should be, and that the resulting concentration risk poses a problem for capital flows as well and this despite increasing interconnectedness between private and public markets. This is a particularly pressing concern for a sustainable transition because funds for innovative companies are simply not available.

GRIP Comment

It was to be expected that all speakers would recognize the importance of capital markets in dealing with some of the world’s biggest challenges. What was slightly more surprising was the positivity that we observed imbuing many of the sessions.

The speakers were far too intelligent and knowledgeable not to recognize the complex nature and scale of the problems, but seemed to be genuinely confident about the ability of developed economies to deal with these – the proviso being a stable regulatory and economic environment that would permit effective and efficient capital formation and investment.

One issue not touched on during the conference was that the track record of public / private partnerships in effectively addressing infrastructure or environmental challenges even in developed countries with seemingly well-regulated markets (eg the past performance of water utilities in the UK) is not exactly reassuring.

And this raises an interesting question to what extent private capital markets will actually be able to help address some of the bigger challenges outlined. Particularly in developing countries where regulatory and political stability is something that investors are even less likely to be able to take for granted.