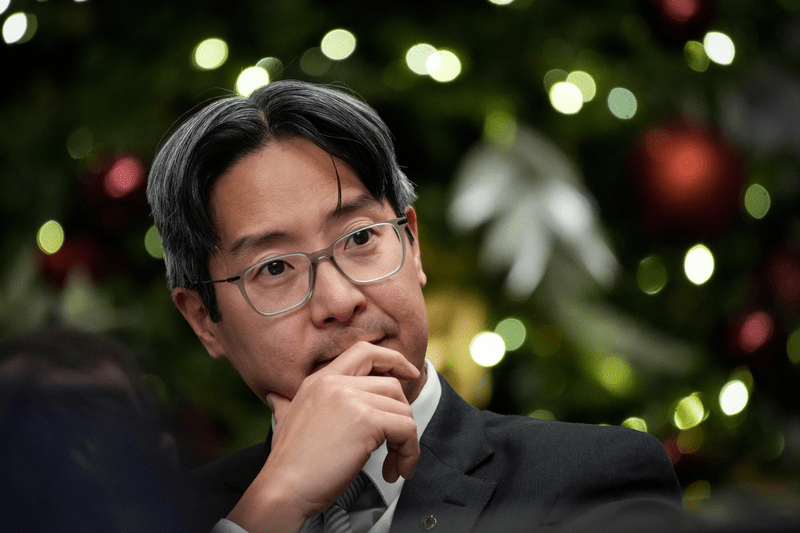

Key long-term banking trends “pose deep threats to trust in banking and warrant our collective attention” according to Acting Comptroller Michael J. Hsu. In important remarks delivered at the Exchequer Club in Washington D.C, he also suggested that these trends have been evolving incrementally and “are underappreciated by the public.”

Hsu pointed out the remarkable growth in the banking sector – from five large banks (assets of at least $100 billion) 30 years ago to 32 large banks with aggregate assets exceeding $17 trillion today. He pointed out that growth in this sector is simply reflecting rapid economic growth – with US GDP at $6.9 trillion 30 years ago, and $27.4 trillion today.

Community and mid-size banks

An interesting and slightly unexpected facet of the data presented in the remarks, but not explored further, is that the total bank assets held by “[c]ommunity and midsize banks in aggregate have been relatively stable” against this backdrop of economic growth.

According to Hsu continuing US economic growth will require substantial growth in large banks even in a scenario of an unprecedented and “massive increase in the number and size of community and midsize banks.” This means that by 2030, when US GDP is forecast to exceed $40 trillion, large banks are likely to hold $20-23 trillion in assets – roughly double of the US banking system today.

Hsu pointed to last year’s bank failures as a sort of wake-up call, suggesting that “regulation reforms in areas like liquidity and long-term debt” are needed. He drew a parallel between banking and building regulations suggesting that “[t]he larger and more complex the buildings, the more stringent the building codes need to be” and suggested four regulation pillars that are “critical to maintaining trust.” These are mapped below against the regulatory measures being worked on by the OCC and federal banking agencies.

| Objective | Regulatory action | |

|---|---|---|

| Capital | Absorb losses | Revision of capital requirements applicable to large banks and banks with significant trading activity |

| Liquidity | Mitigate and withstand runs | Targeted enhancements to large bank liquidity rules |

| Operational resilience | Maintain critical operations | Operational resilience requirements for large banks’ critical operations. Revision of OCC policy on enforcement actions related to banks with persistent weakness |

| Recovery planning | Ensure options in stress | OCC recovery planning guidance for large banks. Long-term debt and resolution reforms to prevent “too big to fail” scenarios |

Moving on from the growth of large banks Hsu pointed out the increasing complexity of bank and nonbank relationships, which is “creating greater interdependencies” in a banking ecosystem that encompasses fintechs.

Digitalization of banking is transformational and is being primarily led by fintechs who partner with banks directly and indirectly to execute on services. Banks, in turn, rely on nonbank entities to support operations and functions. Both depend “on a handful of large cloud service providers” to support digitalization.

Hsu suggests that banking “is beginning to resemble global manufacturing supply chains”, with the public “unwittingly expecting banks and bank regulators to cover problems no matter where they occur in the chain.” He pointed to the recent bankruptcy of Synapse as an example of the blurring of the line “between where a bank ends and where a nonbank begins.”

Innovation or confusion?

One of the issues is that there is a gap between businesses, such as fintechs, that are regulated at the state level (as state-licensed money services businesses) and those facing prudential federal bank agency oversight. Proponents of this regime claim that this has enabled innovation, but according to Hsu it has “enabled customer confusion” instead with fintechs playing “fast and loose with how they market their services and their relationships to FDIC insurance, which does not cover their failures” (emphasis in original text).

The OCC and Federal banking agencies are going to be engaging with fintechs and other nonbank entities more closely in future as emerging issues are explored as a matter of priority.

Hsu concluded his remarks by addressing what he sees as a “worrisome trend of fragmentation” emerging in banking law at the state and local level. “This trend seems to reflect the rise of polarization writ large. To varying degrees the culture wars, identity politics, and weaponization of finance are pushing toward greater and greater fragmentation of the US financial system,” he said.

Hsu sees the OCC as a bulwark against fragmentation. He sees the concept of pre-emption as one “critical to national banking” and suggests that the OCC will continue to defend it vigorously while embracing and developing a more nuanced analysis of this following the Supreme Court Decision in Cantero v. Bank of America.

GRIP Comment

A fascinating speech, particularly for those involved in any type of strategic decision making. Note the opposing trends – one of large bank dominance fuelled by economic expansion, the other of the potential for regulatory fragmentation at the state and local level.

An interesting question here is whether there is a correlation between these two trends – explicitly whether the large banks benefit competitively not only from economies of scale but also from the national regulatory framework in which they primarily operate.

The conclusion that the financial system is moving in the direction of a supply chain model is useful when considering efforts by regulators to instil discipline by and resilience in financial institutions when it comes to the relationships with third-parties supporting critical processes.

Effective supply chains can increase productivity and minimize cost and time – but that is assuming that they operate smoothly. Consider the supply chain issues experienced by businesses as a result of unexpected disruption such as the pandemic or war (or indeed a flawed code deployment!) and it becomes very clear why regulators are worried about the resilience of the financial ecosystem.