Crypto investors have endured a bruising six months. In what has been dubbed ‘the crypto winter’, digital asset values have plunged, with the crypto market shedding around $2trn by mid-July. Bitcoin, the most actively traded cryptocurrency, had seen its value cut in half to around $23,000 in mid-August from roughly $47,000 at the end of March.

Other crypto assets have performed much worse. In May, TerraUSD – a supposed stablecoin – and Luna – the cryptocurrency that it was pegged to – both collapsed in a combined meltdown that saw around $60bn of market value wiped out. Luna tokens that had been trading at more than $100 in April sank to a fraction of a cent.

The carnage became contagious. Cryptocurrency lender Celsius Network filed for bankruptcy protection in July after it had halted customer withdrawals as crypto prices crashed a month earlier. Fellow crypto lender and digital asset broker Voyager Digital was also forced to file for bankruptcy after suspending trading and halting withdrawals. Crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, meanwhile, was ordered by a court to liquidate after its crypto investments – including a bet on Luna – cratered.

The watchful gaze

That turmoil came as regulators were already ramping up their scrutiny of crypto markets. The losses investors have suffered over the past six months – many of them retail investors, lured into the market by the promise of making a quick buck – means the regulatory backdrop is only going to get tougher.

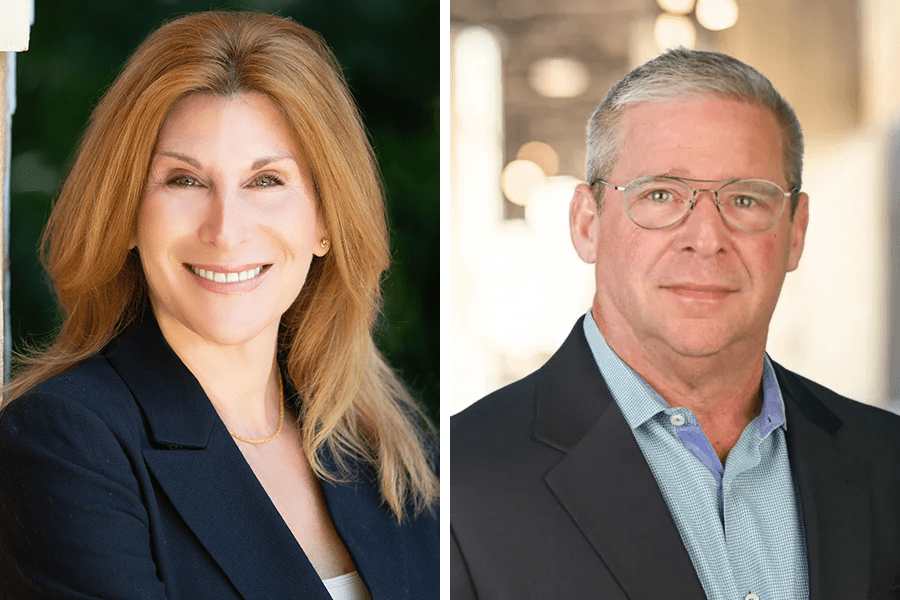

“The market downturn in general has absolutely increased regulatory scrutiny,” says Amanda Tuminelli, a lawyer at disputes and investigations specialist Kobre & Kim. “There are a few reasons for this. One is that people have lost a lot of money and their complaints have caused regulators such as the Consumer Protection Bureau to sit up and ask if people were misled. People don’t necessarily ask a lot of questions when they’re making double-digit returns on their investments, but when they suddenly lose all their money, they want to know what happened.”

And enforcement activity is already accelerating. In August, the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned virtual currency ‘mixer’ Tornado Cash – a service that allows users to move crypto funds anonymously – accusing it of laundering more than $7bn of crypto for cybercriminals.

Tuminelli says the sanctioning of Tornado Cash is an example of regulation by enforcement, and it is catching crypto companies off-guard.

“This is a trend in the US, where there aren’t clear guidelines or rules, but regulators are coming in after the fact and saying ‘you broke a law’,” says Tuminelli. “Sometimes people in the crypto community only find out they broke the law after they get served a subpoena, even though they may have been doing their best to comply with regulation that’s changing on a near-daily basis.”

“While there is a consensus in the crypto community that the Bitcoin and Ethereum networks are decentralized enough to be considered commodities, I don’t think that applies to any other network.”

Amanda Tuminelli, lawyer, Kobre & Kim

The recent market rout comes as the turf war between the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) over who should regulate the crypto market, remains unresolved. That is despite a proposed bipartisan crypto bill – the Responsible Financial Innovation Act – tabled in June by Democrat Kirsten Gillibrand and Republican Cynthia Lummis, which asserted that digital assets are more similar to commodities than securities, potentially paving the way for the CFTC to assume the lead role.

“The bill is very significant in terms of drawing much clearer boundaries between the different enforcement agencies that have all piled into the crypto space, but its prospects for passing and becoming law in its current form are not particularly great,” says David McGill, a partner at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe.

Despite Lummis and Gillibrand’s assertion that crypto assets are more akin to commodities, that view is by no means unanimous.

“While there is a consensus in the crypto community that the Bitcoin and Ethereum networks are decentralized enough to be considered commodities, I don’t think that applies to any other network,” says Tuminelli. “The bill was a great effort and it’s good to see Congress members trying to get their arms around the topic and trying to be out in front of this, but the turf war is still going on.”

Is crypto a security?

The SEC shows no signs of easing back from policing the crypto market either. In July, the SEC charged a former Coinbase manager, along with his brother and a friend, for insider trading on more than two dozen crypto assets – almost half of which the SEC decided should be classified as securities.

“The SEC, almost out of nowhere, took the position that nine of the assets in question were securities,” says McGill. “The net effect of this is that everybody who has a crypto project out there with US ties, and that has a token associated with it, is now a lot more concerned that the SEC may ultimately start to come after them for conducting unregistered securities offerings.”

The SEC has also reportedly launched an investigation into Coinbase itself for allowing customers in the US to trade unregistered securities. That probe could have significant implications for the way crypto exchanges currently operate.

“If the SEC was to prevail, it would extend beyond Coinbase and therefore any exchange listing similar digital tokens would have to register with the SEC and follow all the rules that go along with operating as a securities exchange,” says Jonathan Marcus, a partner at Reed Smith.

And it’s not just US regulators stepping up their oversight of crypto markets. In June, the European Union announced new rules that will ensure crypto assets can be traced in the same way as traditional money transfers, in an effort to prevent money laundering, terrorist financing and other crimes.

“This is going to bring a lot of entities into the scope of having to do a lot more anti-money-laundering (AML) checks on their customers. It’s also going to impact on unhosted wallets,” says Deborah Hutton, a partner at Eversheds Sutherland.

“The Gillibrand-Lummis bill was really only the first step in a long process and the sponsors of the bill understood that.”

Lisa Ledbetter, partner, Reed Smith

Because unhosted wallets enable users to hold their cryptocurrencies away from an exchange, it effectively allows them to remain anonymous. Under the new EU rules, any company transacting with an unhosted wallet account will need to ensure they have carried out the necessary AML checks on the owner of the wallet. For smaller companies that don’t have large compliance teams, that is likely to be an onerous and costly process.

“There’s going to be quite a bit of disruption as people have to start complying with these requirements,” says Hutton.

The regulatory agenda is likely to shift up a gear next year. The posturing for oversight in the US, for instance, is expected to redouble following November’s midterm elections.

“The enforcement push is only going to intensify as we get past the election period, because there’s going to be a new round of jockeying by these agencies to persuade the new Congress that they’re the most appropriate agency to hold principal responsibility for policing cryptocurrency markets and regulations,” says McGill.

Lisa Ledbetter, a partner at Reed Smith, says the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s digital assets report, due out in the fall, may yet provide some further clues on where the regulation is heading, particularly around how it can mitigate risks. The legislative drumbeat in the US is also likely to get even louder after the midterm elections. “The Gillibrand-Lummis bill was really only the first step in a long process and the sponsors of the bill understood that,” says Ledbetter. “They have said that this is for us all to understand the issues, discuss them and come up with the right approach, so it’s really just kicking off the process.”