With an overwhelming number of developments in AI and a fast-evolving regulatory landscape, we cut through the noise and take a closer look at what you need to know about the regulation of AI today to ensure that you strike the right balance between enabling innovation and managing risks.

Why the push to regulate AI now?

In broad and simple terms, AI is the ability of machines to undertake processes that have, to date, been performed by human intelligence. Generative AI and large learning models are a type of AI that creates new content such as images, music or text through complex algorithms that learn from patterns in training data. The technology can provide human-like responses and be used for everything from generating a travel itinerary for your next trip abroad to creating a bespoke piece of digital art based on a simple text prompt.

The progress of generative AI technology in recent months, especially OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Dall-E2, has captivated the imaginations of members of the public and law-makers alike. The rapid pace of progress has, however, brought concerns about bias, discrimination and inaccuracy, even human extinction at the hands of an artificial superintelligence!

In March this year, over a thousand industry leaders and experts, including engineers from the largest tech companies, called for a halt of AI development in an open letter. The letter asked for a six-month halt on the development of more powerful AI technology due to “profound risks to society and humanity” that flow from “an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one — not even their creators — can understand, predict, or reliably control”.

Legislators, already in the process of developing laws and legal frameworks in this area to safeguard individual rights and reflect a consensus around AI ethical principles, are reacting to this catalyst.

The legislative and regulatory landscape

Whilst the legislative and regulatory landscape is still evolving, business users of AI are advised to build forward-looking compliance programmes, policies and procedures that can adapt to incoming legislation and take account of existing regulation.

The EU’s regulatory approach

The EU’s AI Act (the “Act”) is nearing finalisation. Now at the trilogue stage, adoption is likely later this year or early 2024, although it is expected that there will be an implementation period, possibly for up to two years. The Act is sector-agnostic and, similar to the GDPR, has extra-territorial effect and serious fines for violations.

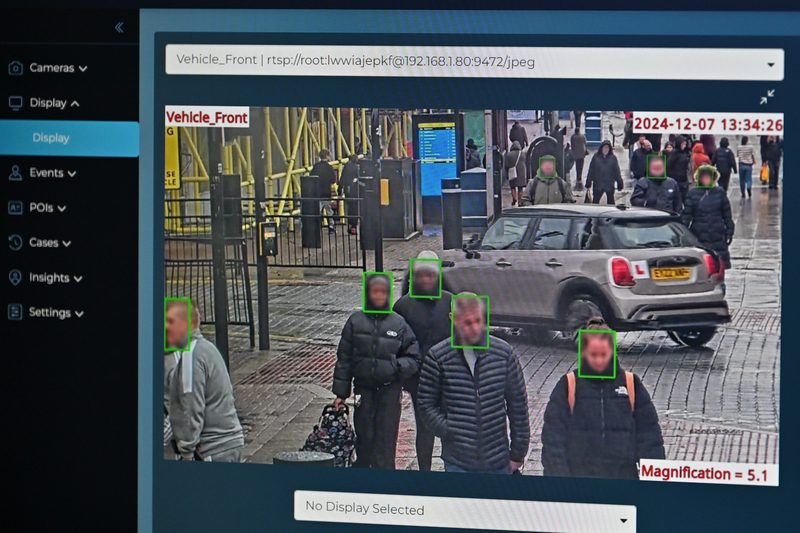

The Act, which focuses on the level of risk that AI systems generate, distinguishes between applications that are considered to pose an unacceptable risk of harm, which are prohibited, and those that are high risk, and will be subject to various testing, registration, certification, governance, transparency, oversight and data security requirements. AI systems deemed an unacceptable risk are those that purposefully manipulate, exploit vulnerabilities or are used for social scoring. In a recent round of amendments in the European Parliament, real-time biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces, predictive policing systems (based, e.g., on past criminal behaviour etc.) and emotion recognition systems were also moved into this list of banned of AI applications.

EU and US officials announced … that they intend to develop expediently, a joint emergency code of conduct, that countries around the world could adopt as an interim measure.

High risk systems include AI deployment in autonomous vehicles or medical technology. The Act categorises other systems as not high risk, such as spam filters or video games, for which basic transparency requirements will be necessary. The latest compromise amendments to the EU AI Act from the European Parliament also introduce extensive obligations in relation to general purpose AI systems and foundational models (including systems such as ChatGPT). See: article The proposed regulation of AI Foundation models and General Purpose AI under the draft European AI Act. (Fieldfisher).

Given the global and rapid uptake of AI, EU and US officials announced at the EU-US Trade and Technology Council in May that they intend to develop expediently, a joint emergency code of conduct, that countries around the world could adopt as an interim measure whilst legislative frameworks are debated and finalised.

EU data protection authorities have also begun to produce guidance on how the EU GDPR (which will continue to apply whenever personal data is involved) is to be applied in the context of AI. For example, the CNIL has published a set of resources on AI for privacy professionals, consisting of an AI – GDPR compliance guide and a self-assessment guide for AI systems. Recent statements by French and German data protection authorities also indicate that the AI Act is likely to be supervised by the EU’s existing data protection regulators.

The UK’s regulatory approach

The UK’s approach to AI does not envisage a general AI law, but instead aims at the creation of sector-specific rules for AI. UK users of AI will therefore need to map out which laws apply to their specific use case. In the UK, a variety of existing laws, such as the UK GDPR, Data Protection Act 2018, Human Rights Act 1998 and Equality Act 2010 potentially apply to AI.

The UK government’s white paper asks existing regulators including the ICO, the CMA, the FCA, Ofcom, the Health and Safety Executive, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and the Human Rights Commission, to implement a set of five general AI principles (security, transparency, fairness, accountability and contestability).

Businesses are encouraged to keep an eye out for guidance issued by their relevant regulator(s) to ensure that they understand how existing laws in their sector will be applied .

It may be that the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF), which was formed in 2020 and brings together the ICO, CMA, Ofcom and FCA, will take on a leading role in developing guidance on AI for the UK’s digital sector. Whilst the white paper’s suggestions are not binding on regulators and the white paper does not expand regulators’ existing mandates, it hints at the potential introduction of a statutory duty following an initial monitoring period that will require regulators to have due regard for the AI principles. Businesses are therefore encouraged to keep an eye out for guidance issued by their relevant regulator(s) to ensure that they understand how existing laws in their sector will be applied and enforced in the context of AI.

The UK’s data protection regulator, the ICO, produced detailed guidance in 2020 on how the UK’s data protection rules are to be interpreted in the context of AI. The guidance, updated in March 2023, is broadly structured along data protection’s foundational principles, namely lawfulness, fairness, and transparency; purpose limitation; data minimisation; accuracy; storage limitation; and security and accountability.

Implementing AI systems

From a data protection perspective when implementing AI systems it is important to consider:

Your status as a controller or processor

The GDPR defines a controller as the entity that determines the purpose and means of processing. In most cases, businesses buying in AI as a service are likely to determine the purposes of the processing (by determining the scope of the AI’s use). This points towards users taking on a controller role. However, given the complexity involved in AI decision-making, providers are likely better positioned to determine the means of processing. Guidance by the EDPB and ICO recognises that the determination of the non-essential means of processing can be left to processors.

Users will need to look at their use of AI on a case-by-case basis to determine the parties’ respective roles under the GDPR.

The AI industry also appears to support the view that users act as controllers (and providers act as processors), with most providers having structured their data processing agreements accordingly. Notwithstanding this, users will need to look at their use of AI on a case-by-case basis to determine the parties’ respective roles under the GDPR (see our section on Input data below for more on this). Leonie Power and Nuria Pastor also consider this issue further in the context of considering how to carry out a data protection impact assessment in an AI context. See: article AI & privacy compliance: getting data protection impact assessments right (Fieldfisher).

The types of data in play: training, input and output data

When considering data in the context of AI, it can be useful to distinguish between training data, which is used by the provider to train the AI, input data, which is fed into the AI by users, and output data, which is produced by the AI in response to input by users.

- Training data Where an AI solution has been trained on personal data and such data remains identifiable in the final solution, users should ensure that there is a lawful basis for the continued processing of such data, recognizing that the lawful basis relied on for training purposes may not extend to the user’s commercial use of the solution. It may therefore be wise for users to seek assurances from providers that their AI does not incorporate personal data or that the provider has procured all necessary rights for the continued and lawful processing of any personal data that is included in the solution. It is likely to be necessary to carry out some checks that this is the case rather than relying solely on contractual warranties.

- Input data UK and EU data protection law generally prohibit the processing of personal data for secondary purposes that are not compatible with the original purpose for which such data was collected. This means that users of AI need to consider carefully whether feeding personal data into an AI solution is compatible with the purpose for which the relevant data was originally collected. The practice by some AI providers to require their users to obtain all necessary rights to enable the provider to use input data for research and development purposes is problematic in this context, as users are unlikely to have collected the data for such purposes. Where a provider uses input data for its own purposes, users and providers will need to ensure that the contract between them recognises the provider’s separate controller role in carrying out such processing activities for its own purposes.

- Output data In relation to output data, users will need to consider the risk of an AI solution producing inaccurate personal data by, for example, creating wrong associations or insights in relation to a data subject.

The need for human oversight and intervention

Where personal data is involved, the GDPR’s rules on automated decision-making need to be considered. Article 22(1) of GDPR prohibits solely automated decisions, which have legal effects on, or similarly significantly affect, a data subject.

To rely on automated decision-making users can rely on one of three limited exceptions, explicit consent, necessary for the performance of a contract, or authorised by law. Alternatively, users can ensure that their use of AI is subject to a meaningful degree of human control and oversight (thereby taking it outside of the scope of Article 22(1)). Even where reliance can be placed on one of the three exceptions, the use of automated decision making is subject to an individual’s right to contest decisions and obtain human intervention.

In practice, to comply with the ICO’s guidance and the GDPR’s principles of fairness, transparency and accountability, many uses of AI will require a degree of human control and oversight.

Many uses of AI will require a degree of human control and oversight.

It is worth noting that the UK’s Data Protection and Digital Information (No. 2) Bill, which is set to reform the UK’s data protection regime post Brexit, proposes a softening of the restrictions on automated decision-making. You can find more information on the proposed changes to Article 22 in one of our briefings.

Even where no personal data is involved, other laws may require a degree of human oversight and control. For example, in the EU, the AI Act is set to introduce a requirement for human oversight for high-risk AI systems.

Data subject rights

Feeding personal data into third-party AI applications can also create issues with users’ ability to comply with their own data protection obligations, especially in respect to data subjects’ rights to access, deletion and rectification. Generative AI solutions often use input data to improve their decision-making, which can make it hard to facilitate data subject rights, as the input data may become intermingled with the AI’s decision-making algorithm.

To reduce the risk of being unable to fulfil data subject requests because, for example, the relevant data is hard to trace, extract or separate from the AI system, it is important to consider how data subject rights will be complied with prior to implementation. AI systems will either need to be designed to facilitate data subject rights effectively, or, alternatively, be built so as to prevent the integration of personal data into the model.

Transparency

Article 13 and 14 of the GDPR require that individuals are informed if their data is subject to automated decision–making that falls within the scope of Article 22 GDPR. This includes meaningful information about the logic involved in such decision-making and an explanation of the significance and likely consequences for individuals.

Even where the use of AI does not qualify as automated decision-making under Article 22(1), it is clear from the ICO’s guidance that the ICO expects users to be transparent about their use of AI in order to achieve compliance with the UK GDPR’s principles of fairness and transparency.

There is a clear need to implement standards by which AI applications are held to account and their use is safeguarded within appropriate ethical boundaries.

Without doubt, the use of AI will become increasingly prevalent across business and society. Despite its tremendous benefits, there is a clear need to implement standards by which AI applications are held to account and their use is safeguarded within appropriate ethical boundaries. Whilst we have seen legislation struggle to keep up with the advancement of technology over the years, there is something of a consensus amongst the stakeholders in the AI field that, in order to ensure the safe and responsible use of AI, legal guardrails are required sooner rather than later.

What shape those measures may take will differ across countries and continents but AI providers and users adhering to the tenets of data protection and broader accountability principles will be well placed to meet the demands of future legislation and regulatory guidance.

Lorna Cropper, director, is a data protection lawyer working in the Technology and Data team. Max Burdyl is a commercial and data protection lawyer with a background in financial services, software and technology. Fieldfisher