Donald Trump’s White House return leaves Beijing both concerned and optimistic. On the one hand there are worries about tariff wars, import bans and confrontational rhetoric on trade coming from Washington. But, at the same time, Trump’s unpredictability and strained trade relationship with certain countries gives Beijing the chance to step in and fill the vacuum.

There is also a third, though less likely scenario, in which both sides maintain a friendlier tone than in the past and work together. Beijing would love such an arrangement, but it’s hard to say the same for Washington, especially given Trump’s past as well as recent rhetoric during the election campaign.

For now, the initial formalities have been completed. The Chinese premier has called and congratulated Trump on his election victory, according to the state news agency Xinhau.

“Xi called for the two countries to strengthen dialogue and communication, properly manage differences, and expand mutually beneficial cooperation,” the brief news story says.

As a sign of traditional Chinese diplomacy, there is quite a lot to unpack in that single line. There is a reference to issues in the past, a mention of what current priorities should be, and a green flag for future cooperation from China.

Bracing for confrontation

Trump’s return to the White House is clearly a source of concern for Beijing. But latest bilateral trade figures can give Chinese officials some temporary hope. According to the FT: “China’s exports soared in October and its trade surplus ballooned.”

Experts have told the paper this was partly because exporters predicted a Trump victory in the presidential race and front-loaded shipments in order to avoid heavier tariffs after the official transfer of power at the White House in January.

And the fact that Chinese exports are doing well could provoke Trump. After all, he built part of his election campaign around the idea of imposing heavy tariffs on imports from China, and prioritising US interests and production at home.

In retaliation, Trump will consider moving ahead with his promised 60% hike in tariffs on Chinese goods. The consequences of that will certainly be far-reaching. According to estimates by Investment Bank Macquarie, this could slash Chinese economic growth by 2%.

He could also revoke the ‘permanent normal trade relations’ status given to China decades ago. We can expect a disruption, too, in sectors such as technology and in global supply chains.

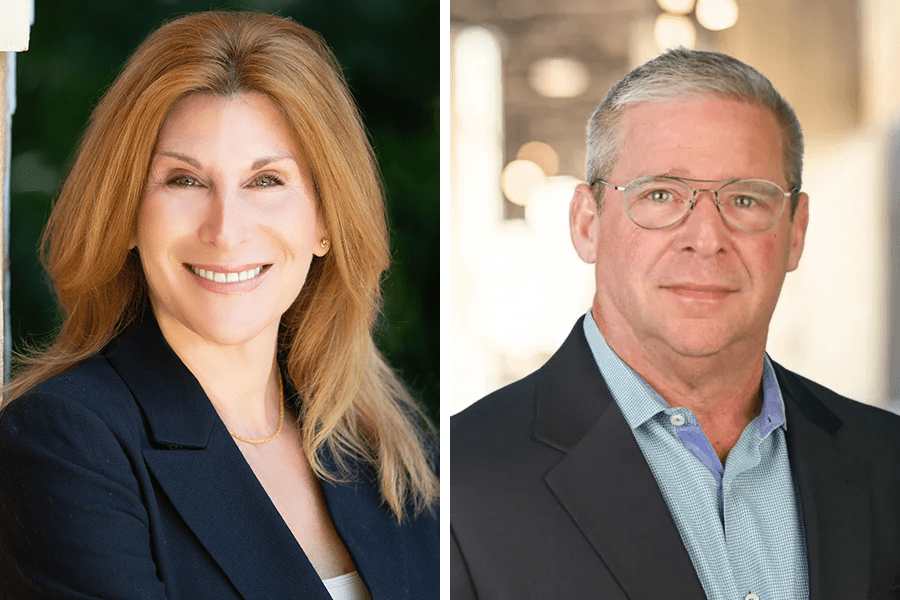

Experts believe the degree or severity of Trump’s retaliation will also be determined by who ends up being in his cabinet. The New York Times reported late on Monday that Marco Rubio, a known China critic, could become secretary of state. There were also reports that the key position of national security adviser could go to Mike Waltz, another China sceptic.

Some of the other names within his inner circle, like former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Robert Lighthizer and John Paulson, are all well-known China critics. Chances of them being in key positions in the new administration are also high.

How could Beijing respond?

Beijing’s top priority would be to maintain the current positive momentum in trade with the US. This is particularly important given the recent sluggish growth in its economy. As things stand, confrontation, either in rhetoric or action, doesn’t serve Chinese interests.

That, however, doesn’t mean Beijing is not prepared for the situation to deteriorate. Wang Dong, a professor of international relations at Peking University, recently told Chinese media: “Trump 2.0 is likely to be more destructive than the 2017 version.” Here are some of the steps Beijing is taking to secure its interest.

At home, Beijing has announced a $1.4 trillion fiscal package “to bail out local governments and help shore up its faltering economy,” as reported by the FT. The announcement comes in anticipation of increased trade tensions with the US.

Speaking of trade, the chipmaking industry has been one key area of confrontation between the two countries. To minimise the impact of any potential US bans, China’s semiconductor industry is purchasing foreign equipment, investing in overseas talent and also forging new alliances, according to reports.

China’s tech sector is also far more ‘self-sufficient and domestic focussed’ compared to 2016 when Trump took office for the first time. As an example, there were only four government procurement projects worth a total of $1.4 million at the time. That number has now risen to 169, recent reports suggest.

China can also impose its own bans to hurt American firms. For example the US drone maker Skydio was recently sanctioned and Chinese firms have been banned from providing it with critical components. Beijing won’t shy away from taking similar action in other sectors if needed.

New alliances?

Experts believe Trump’s America First slogan and harsh increases in tariffs could prove unpopular in Europe and beyond, providing Beijing with the chance to step in and fill the vacuum by forging new alliances.

There are also opportunities closer to home. According to Parvez Khan, director at IPK European Strategy: “China has been building on already strong bilateral relations across South Asia, for instance, as countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan increasingly look to it for funding on large projects.”

“Those bilateral relations could easily develop into a network in a world where the US does not tend to its own bilateral relations with those countries,” he told us.

Beijing is also reaching out to the Gulf. Reports last week said China had chosen Saudi Arabia for its first sale in three years of US dollar sovereign bonds. “The choice of Saudi Arabia for this new issuance is symbolic of the deepening financial ties between the two countries,” the report said.

Moving forward

Beijing has clearly shown a willingness to hit the restart button and work together with US officials. This could lead to the potential third scenario we highlighted above, and there are reasons why China would prefer this more than anything else under current circumstances.

As for the US, it remains to be seen whether any escalation in tension with China will serve or secure American interests in the long term. Khan believes the US needs to strike a balance between how much pressure it can put on China via its strength in bilateral trade relations, and Washington’s vulnerabilities vis-a-vis its relations in the region.

Getting that balance right will be the key to moving forward. The world’s two largest economies must avoid hurting each other to the extent that the fallout will disrupt the entire global trade order.

Unlike some of the hardcore China critics in his inner circle, Trump’s personal opinion of Beijing has proved somewhat unstable. He has accused China of exporting COVID to the world, but he has also called Xi “a brilliant guy.” Officials in Beijing will certainly hope to see more of the latter over the coming four years.