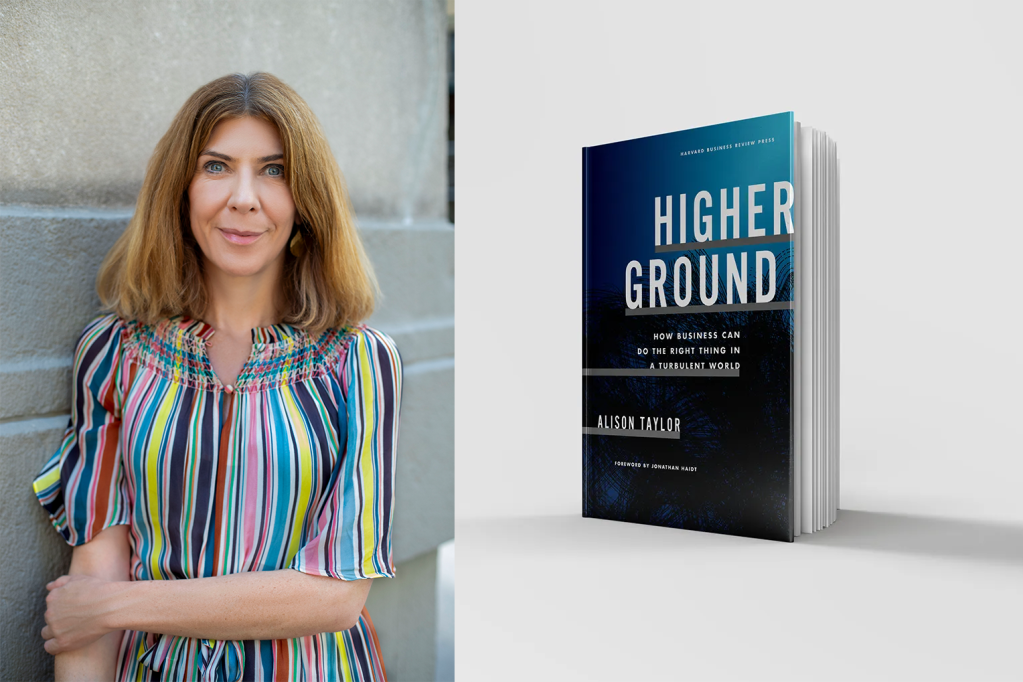

In a completely uncomfortable era when there is mounting caution over using the term “ESG” – despite continued support of many of its goals – increased greenwashing enforcement and a mounting backlash against those considerations as antithetical to fiduciary duty, along comes Alison Taylor’s new book.

The New York University Stern School of Business associate professor’s perfect timing is only a small part of the incredible rewards her insights bring.

This book tells you why everyone wins when businesses act responsibly, and its author assures businesses they do not have to be everything to everybody.

They don’t have to have a huge ESG mandate. They will get some things wrong, not please everyone, and have some discernible contradictions at times. But the difference between responsible businesses and others is that the former keeps trying and caring about managing the impact their business operations have on society.

“I will establish that making your best effort to do no harm ought to take priority over involving your company in tangential popular causes.”

Alison Taylor in her book, Higher Ground

If you follow Alison on LinkedIn – I highly recommend this – you will see her explain that whatever term we use, what it takes to be a responsible business is still controversial, political and contested. But she says, “let’s have this debate”. Insisting ethical behavior is not relevant is a huge part of the problem. (And how partisan is it to object to warehouse workers being forced to stand next to a dead body all day, or a business colluding with its main regulator to circumvent fulsome safety inspections?)

Practical advice

Alison realizes that books that are theoretical explorations have limited value, and she avoids this to get right down to business. Her book offers substantive guidance on how to figure out the right thing to do for your company.

She walks you through that process of decision-making and business planning – underscoring the overarching principle that the business is there to make money and should be, but is also there because of the social license to operate that societies grant corporations.

She says: “Make your core product well, clean up your messes, do no harm, and treat human beings with dignity and respect.” And, helpfully, she dives in and shows you how – with examples, explanations, ideas and insights from others who have grappled with how to measure their business’s potential impacts on human beings.

It’s not just about risk and reputation – it’s about how your company affects the world. “I will establish that making your best effort to do no harm ought to take priority over involving your company in tangential popular causes,” she promises at the outset.

And, really, do businesses have much choice in not embracing at least some version of a “do no harm” posture in this world? “We are constantly given opportunities to peer into the chasm between images a company takes care to project and what it’s like to actually like to work there,” she reminds us. (Ah, yes, the ubiquity of social media.)

A company can let the bottom-up phenomena of unfiltered employee and customer views control the narrative – or the business itself can.

Some ‘what if’ scenarios

I pressed Alison on certain points. What if a business is benefitting society through a number of well-thought-out initiatives that its stakeholders believe align with its values, spending capabilities and its expertise, but then a global recession hits – or a global pandemic. You have to recalibrate your spending and corporate priorities, don’t you?

First, she reminds me that if you are scoping and implementing sustainability efforts correctly, then these initiatives should be investments with returns and not just costs. (How to do that is all in her book!)

“Surveillance is challenging for compliance teams because they fear regulatory backlash if they don’t use every tool out there; but if you talk to regulators, they want a proportional, strategic and risk-focused approach to surveillance.”

Alison Taylor

And then she reflects on how the Covid-19 pandemic instigated some meaningful supply-chain resilience efforts and, in some cases, much better treatment of workers.

“One problem here is that we tend to assume all this stuff is a cost center and don’t delineate carefully between initiatives that drive innovation, reduce risk or manage negative externalities. But, if something ambitious – like a regenerative agriculture project – needs to be put on hold, that messaging should come from the CEO.”

I asked her about controlling for bad behavior in workplaces through monitoring and how business leaders can balance their trust in employees with a need to surveil them.

“There are ways to use this technology ethically,” she says. “Surveillance is challenging for compliance teams because they fear regulatory backlash if they don’t use every tool out there; but if you talk to regulators, they want a proportional, strategic and risk-focused approach to surveillance.”

Number 1 mistake

Finally, I ask her what is the biggest mistake businesses make in trying to tackle their understanding of their social impact and developing a strategy for being a better corporate citizen. I told her my guess was that businesses tend to bite off more than they can chew.

She said it was. “Ticking the box on 40 things rather than focusing on a few problems they can actually solve” is a big problem. “Be honest about what you can actually achieve, when you might need collective action or supportive regulation to get you over the finish line. Quite possibly, you can be a part of that action or that agitation for regulations instead of just dropping the ball.

“You don’t want to be piecemeal and inconsistent in your pace and scope, but you cannot address a dozen of societal challenges, either. Ask how your business can contribute to a couple of articulated goals,” she said.

Learn more about the author, the book and where to order your copy.