Regulators

- Financial regulator: FINMA – The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority

(in German) Eidgenössische Finanzmarktaufsicht

(in French) Autorité fédérale de surveillance des marchés financiers

(in Italian) Autorità federale di vigilanza sui mercati finanziari

(in Romansh) Autoritad federala per la surveglianza dals martgads da finanzas

FINMA is Switzerland’s independent financial-markets regulator, and its mandate is to supervise banks, insurance companies, financial institutions, collective investment schemes, and their asset managers and fund management companies. - Data protection authority: FDPIC – The Federal Data Protection and Information Commissioner

The FDPIC is responsible for tasks in the areas of data protection and for upholding the principle of freedom of information.

Banking ecosystem

- Largest banks: Following the merger of Credit Suisse with UBS, there are still four systemically important banks in Switzerland according to FINMA: UBS, the Raiffeisen Group, Zürcher Kantonalbank, and PostFinance.

- Central bank: SNB – The Swiss National Bank is Switzerland’s central bank. It has the exclusive right to issue banknotes and has a mandate to conduct the country’s monetary policy. It was legally founded in 1905 and started operating in 1907.

- Currency: Swiss Franc (SFr)

Expert snapshot

8 questions in collaboration with Dr Vaïk Müller, Dr Matthias Kuert, and Tina Balzli at CMS Switzerland.

1. Who are the main regulators for financial services in Switzerland and how would you describe their appetite for regulation?

The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) is Switzerland’s main financial market regulator. It is in charge of granting licenses to and performs the ongoing supervision of, inter alia, banks, insurance companies, securities firms, collective investment schemes and their asset managers, as well as fund management companies.

Certain supervisory activities are not directly performed by FINMA but by privately organized institutions licensed or approved by FINMA:

- Client advisers of financial services providers may have to be registered with a registration body approved by FINMA.

- The supervision of listed entities is generally conducted by the applicable bodies of the two Swiss stock exchanges (Swiss Stock Exchange SIX and BX Swiss AG).

- The on-going supervision of portfolio managers is conducted by so-called “Supervisory Organisations” (SO) approved by FINMA.

- Prospectuses of issuers of securities to the public are reviewed and approved by privately organized reviewing bodies approved by FINMA.

FINMA is generally committed to ensuring that Switzerland remains a safe financial center, one offering an adequate level of investor protection and which does not hesitate to open enforcement proceedings against financial institutions to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements, in particular in connection with anti-money-laundering regulations.

The appetite for regulation has increased during the last few years, partially due to the evolution of the international landscape, the technical developments affecting the various market players, and the increasing pressure on the part of the European Union, as well as some issues experienced by large financial institutions.

This increasing regulatory pressure and complexity has translated into a need for additional FINMA guidelines and circulars. However, the volume of such regulatory publications and the number of enforcement proceedings remains relatively light when compared to the position of Switzerland as a major financial center.

2. What are the main sources of regulatory laws in your jurisdiction?

Acts and implementing ordinances

The Swiss financial framework is essentially based on five pillars covering the provision of financial services and the licensing of financial institutions in various domains:

- The Financial Services Act (FinSA) and its implementing ordinance the Financial Services Ordinance, which provide for rules of conduct and prospectus duties in case of public offerings, and introduces a key investor information document for financial instruments largely modeled on EU PRIIPS.

- The Financial Institutions Act (FinIA) and its implementing ordinances, the Financial Institutions Ordinance (FinIO), and the Financial Institutions Ordinance-FINMA (FinIO-FINMA) aiming at harmonizing the licensing requirements for securities firm, trustees, asset and portfolio managers as well as fund management companies.

- The licensing requirements for banks and FinTech companies are set forth in the Swiss Banking Act (BA) and the various related implementing ordinances Banking Ordinance, Accounting Ordinance-FINMA, Capital Adequacy Ordinance (CAO), FINMA Banking Insolvency Ordinance (BIO-FINMA), Liquidity Ordinance, and the Foreign Banks Ordinance-FINMA (FBO-FINMA).

- The Financial Market Infrastructure Act (FMIA), which regulates financial market infrastructures including stock exchanges, MTFs, OTFs, CCPs, CSDs, or payment systems, and also contains rules on trading of OTC derivatives, disclosures required of major shareholders, public takeovers, and insider trading and market manipulation. This is supported by its various implementing ordinances, namely the FINMA Financial Market Infrastructure Ordinance (FMIO-FINMA), the Takeover Ordinance, and the Ordinance on the Recognition of Foreign Trading Venues for the Trading of Equity Securities of Companies with Registered Office in Switzerland.

- The collective investment schemes (CIS) are governed by a specific act, the Collective Investment Schemes Act (CISA), which mainly sets forth the requirements concerning the establishment of Swiss CIS and the marketing and offering of foreign CIS in Switzerland and its various supporting ordinances, namely the Collective Investment Schemes Ordinance (CISO), FINMA Collective Investment Schemes Ordinance (CISO-FINMA), and the Collective Investment Schemes-Bankruptcy Ordinance-FINMA.

FINMA and other supervisory organisations practice

In addition to the acts and implementing ordinances, applicable rules are detailed in FINMA regulatory guidance typically published in circulars and other documents available on FINMA’s website.

Privately organized bodies, such as the various Supervisory Organisations, also regularly publish their practical guidance.

The FINMA Circulars can be accessed here. FINMA also regularly publishes guidance on specific questions to clarify its approach to regulatory oversight. Another important practical document is, for instance, a FAQ document of the registration bodies for client advisers (cf. above) that FINMA took note of, which is available here.

3. How can firms outside Switzerland do financial services business in your country?

The provision of financial services on a cross-border basis without the establishment of a permanent local presence is generally permitted. Switzerland remains a relatively liberal and open market. For instance it still currently does not apply any exchange controls. However, certain requirements may apply to the promoters of financial products and instruments and their client advisers when offering these to retail clients and elective professional clients.

Certain product restrictions may also apply in connection with the offering of collective investment schemes and structured products to retail clients, as well as in connection with insurance products. Establishment of a branch or a representative office is also permitted but generally subject to various requirements set out in the relevant regulations, such as the FBO-FINMA or the FinIA.

On December 21, 2023, the Swiss Federal Council and the UK’s HM Treasury have announced the conclusion of the Bern Financial Services Agreement between the UK and Switzerland. This Agreement introduces mutual recognition to facilitate the provision of various financial services between the two countries. This Agreement must still be voted on by both the Swiss and British Parliaments. Importantly, this agreement does not cover retail clients but generally focuses on institutional and professional clients.

4. What types of activities require a license in your jurisdiction?

The following activities generally trigger a licensing requirement when conducted on a professional basis, absent of any available exemptions set forth in the relevant acts or ordinances:

- accepting public deposits;

- trading in securities in its own name for the account of clients or for its own account on a short term basis (subject to additional conditions);

- acting as a market maker;

- acting as issuing house or derivatives firm;

- managing collective investment schemes;

- managing client’s money based on particular instruction (individual portfolio management);

- administrating trusts, for example acting as a trustee;

- providing insurance coverage; and

- operating a market platform allowing on a discretionary or non-discretionary basis the buying or selling of securities or financial instruments, including investment tokens structured as securities (operation of a stock exchange, a MTF or a OTF).

Financial intermediation subject to Swiss anti-money-laundering regulations does not necessarily trigger a licensing requirement (FINMA license) depending on how operations are structured but generally requires an affiliation with a so-called “self-regulatory organization” (SRO).

Further, the provision of certain financial services defined in the FinSA does not necessarily require a license, but may require having to comply with certain rules of conduct, organizational requirements, and the registration with a supervisory body as well as an affiliation with an ombudsman.

5. What are your top three enforcement fines and briefly explain in a sentence or two why the firms were censured.

The specific enforcement instruments of FINMA are:

- orders to restore compliance with the law;

- declaratory orders and substitute performance;

- professional bans (addressed at individuals);

- publications of orders (“naming and shaming”);

- confiscations (profit disgorgement orders);

- appointments of investing agents; and, as ultima ratio

- revocations of licenses.

However, FINMA does not relinquish the power to impose fines in case of a breach of any of its regulatory provisions. A breach may also be sanctioned by criminal proceedings. In that case, the prosecution is conducted by the competent Federal or Cantonal judicial authorities.

Certain high-profile enforcement proceedings have recently been conducted by FINMA, including those against Credit Suisse in the cases “Archegos” and “Greensill” and in numerous AML-matters.

6. What is the regulatory attitude to crypto?

Switzerland is one of the leading countries when it comes to crypto/blockchain regulations. FINMA was the first regulator to publish dedicated practice formalizing the features of payment, utility and investment tokens and to possess a dedicated desk for FinTech and other crypto-related questions.

FINMA related guidelines and communications are available here.

More recently, we have been observing a hardening of FINMA’s stance with crypto used as payment tokens in the context of the fight against money laundering. This resulted in what can be termed as a “Swiss finish” (an additional layer of safeguards traditionally demanded by Swiss bank regulators) in connection with crypto projects/regulation such as stablecoin issuance.

7. Where does business stand on ESG?

For the time being, Switzerland is essentially relying on self-regulation produced by the leading industry representative professional associations, such as the Swiss Bankers Association (SBA), the Asset Management Association Switzerland (AMAS) and the Swiss Insurance Association (ISA) with a strong focus on fighting “greenwashing.”

These associations have established various guidelines, including definition of sustainable investment objectives, the description of the sustainability approaches applied, accountability in this regard and the audit of implementation by an independent third party.

Based on the development of these self-regulations as well as the European Union’s ongoing work on amending the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), the Swiss Federal Council decided on June 19, 2024 to refrain from introducing state regulation to combat greenwashing in the financial sector at this stage, but has committed to closely monitoring national and international developments in this area.

Aside from the fight against greenwashing, FINMA has introduced certain tangible rules on sustainable finance in two circulars imposing transparency obligations for climate risks on Swiss regulated banks and insurance companies (more details available here), and through guidance on preventing and combating greenwashing targeted at the fund and institutional level (more details available here).

More broadly speaking, the Swiss Code of Obligations imposes rules on non-financial reporting to all Swiss companies with listed debt or equity instruments that have more than 499 employees, and exceed a yearly balance sheet total of CHF20m ($23.3m) or yearly sales of CHF40m ($46.6m). The report must cover environmental matters, in particular CO2 goals, social issues, employee-related issues, and human rights and anti-corruption compliance. These rules and reporting are largely based on the rules of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) of the EU and, consequently, the Swiss government has already announced its intention to assess a possible adaptation of the Swiss rules to the CSRD.

8. What is the Swiss government’s position on data privacy? What are some of the biggest concerns?

As Switzerland is not a member of the EU, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is not applicable in Switzerland, except in a few limited cross-border scenarios.

However, the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection (FADP) had been comprehensively overhauled, and the revised act became effective on September 1, 2023. The FADP remains liberal in its essence, even if some restrictive amendments have been implemented in an attempt to harmonize the FADP with the GDPR-regime.

The powers of the Federal Data Protection and Information Commissioner (FDPIC) have also been reinforced.

As a notable development, on August 14, 2024, the Federal Council approved the corresponding amendment to the Data Protection Ordinance and added the US to the list of countries with adequate data protection for certified US companies in the context of the Swiss-US Data Privacy Framework, which is based on a similar framework concluded between the US and the EU in July 2023.

The recognition of US certified companies will apply from September 15, 2024. This recognition is an important development for Swiss companies.

Recognition of the equivalence of the FDPA with GDPR and EU data protection frameworks by the EU Commission was also a key priority for the Swiss government. The recognition of such equivalence on January 15, 2024 was therefore an important step for the longevity of the recently revised FDPA.

Compliance

Money laundering

New findings from FINMA in 2023 showed that many Swiss banks were falling short in their money-laundering risk analysis and management efforts. FINMA found repeated shortcomings around the money-laundering risk analysis during on-site supervisory reviews at over 30 banks. “A large number of the risk analyses examined did not meet the basic requirements for such an analysis,” FINMA said.

Some of the findings included deficiencies in setting limits to reduce risks, and not having required structural elements to provide an effective and robust analysis.

Following the findings, the Swiss Federal Council also announced plans to strengthen Switzerland’s anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorism financing framework, and has opened a consultation on a draft bill intended to:

- introduce a federal register of companies and their beneficial owners – this would be non-public, and would be managed by the Federal Department of Justice and Police;

- broaden due diligence requirements to involve certain consultancy activities such as legal advice;

- introduce other measures including:

- mechanisms for the prevention of sanctions evasion;

- lower cash payment thresholds for precious metals trading SFr 100,000 to SFr 15,000 ($112,640– $16,896); and

- requiring due diligence for cash payments in real estate.

“The aim is to reinforce the integrity and competitiveness of Switzerland as a financial and business location with a federal register of beneficial owners, due diligence for particularly risky activities in legal professions, as well as other provisions,” the Federal Council said.

Data

Data protection

The Swiss Federal Data Protection Act (the “old DPA” originally dated June 19, 1992) has undergone a complete revision, and the “new DPA” came into force on September 25, 2023. It now complies with the revised Council of Europe Convention 108, and its provisions are similar to EU GDPR – with a few conceptual differences such as legal grounds and sanctions.

Other data protection rules, besides the DPA, include the Swiss Unfair Competition Act (UCA), the Swiss Telecommunications Act, and the Swiss Penal Code.

Notable data breach

In May 2023, Xplain, a Swiss technology and software solutions provider for various government departments, administrative units, and the military force, was hacked by the ransomware gang Play.

As a result of the attack, the hackers obtained thousands of sensitive Federal government files, many of which were subsequently published on their darknet portal.

The Swiss government confirmed that 65,000 government documents were leaked in the breach – representing 5% of the total data package obtained by the hackers. The information included:

- files related to the administrative units of the Federal Department of Justice and Police (FDJP): the Federal Office of Justice, the Federal Office of Police, the State Secretariat for Migration, and the internal IT service center ISC-FDJP (95% of the documents);

- documents related to the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (3%).

About 5,000 of the documents contained sensitive information, technical details, classified information, and account passwords. Personal data, such as names, email addresses, telephone numbers, and addresses, was found in 4,779 of these files. And a few hundred files contained crucial IT system documentation, software or architectural data, and passwords.

New legislation

The Berne Agreement

On December 21, 2023, the Swiss Federal Council and the UK’s HM Treasury announced the signing of an agreement on mutual recognition in specific areas of financial services between the two countries. This agreement is referred to as the Berne Financial Services Agreement. The conclusion of this groundbreaking agreement is the culmination of more than two years of negotiations following the signing of a Joint Statement on June 30, 2020 aiming at enhancing cooperation in financial services between Switzerland and the UK.

The key objective of the agreement is to introduce mutual recognition in order to facilitate the provision of financial services (including insurance services) on a cross-border basis between the two countries, which both face regulatory and commercial challenges connected with access to the EU market in the absence of passporting rights.

Crypto tax

On October 19, 2023, the Swiss Federal Tax Administration updated its tax information on cryptocurrencies. The guidance describes the operation of a blockchain as well as mining and staking, and also addresses the issue of taxation of the various categories of token. The definitions, principles and tax treatment details have non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and airdrops as the primary focus.

Collective Schemes Ordinances

On January 31, 2024, the Swiss Federal Council released the final implementing provisions of the Collective Schemes Ordinances relating to the Limited Qualified Investor Fund (L-QIF). The L-QIF is a new type of investment fund reserved to qualified investors under the Collective Investment Schemes Act. The L-QIF provisions commenced on March 1, 2024.

Technology

Cybersecurity

On May 22, 2024, the Swiss Federal Council released its draft ordinance implementing the reporting requirements in the event of cyber-attack as set out in the Information Security Act. The public consultation period ended in September 2024. The new reporting requirements are expected to apply from January 1, 2025.

The Information Security Act contains a relatively detailed list of operators of “critical infrastructures” subject to the obligation to report cyber-attacks. Among other sectors, such as energy, education and healthcare, certain actors in the financial sector are explicitly included:

- financial institutions subject to the Banking Act;

- insurance companies subject to the Insurance Supervision Act; and

- financial market infrastructures (FMIs) subject to the Financial Market Infrastructure Act.

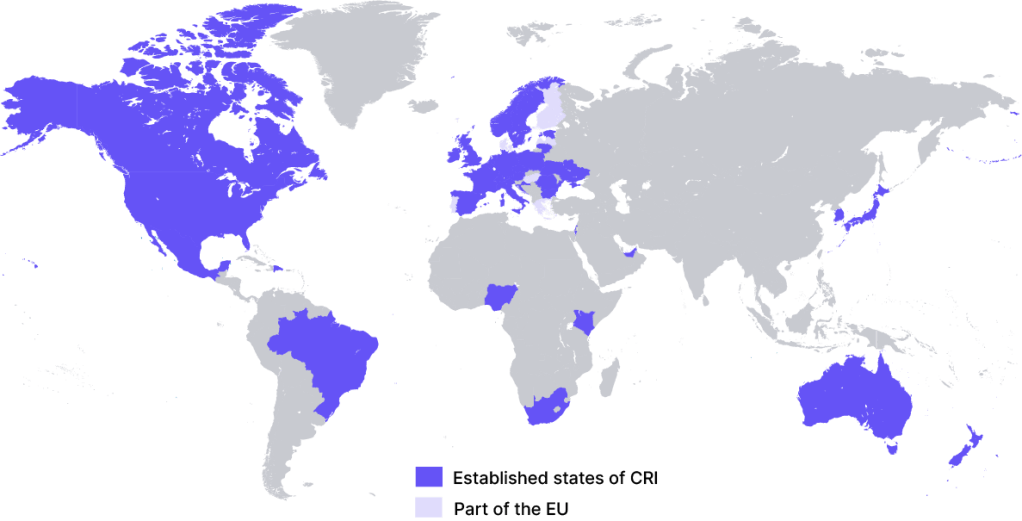

In November 2022, representatives from 36 countries and the EU met to continue their work to fight ransomware, and issued a joint statement after their second International Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI) Summit, convened by the White House.

Since the first meeting in autumn 2021, the CRI members have been working on five core goals:

- increase resilience;

- disrupt ransomware cartels;

- counter money laundering;

- build partnerships with private sector cyber firms; and

- strengthen international cooperation.

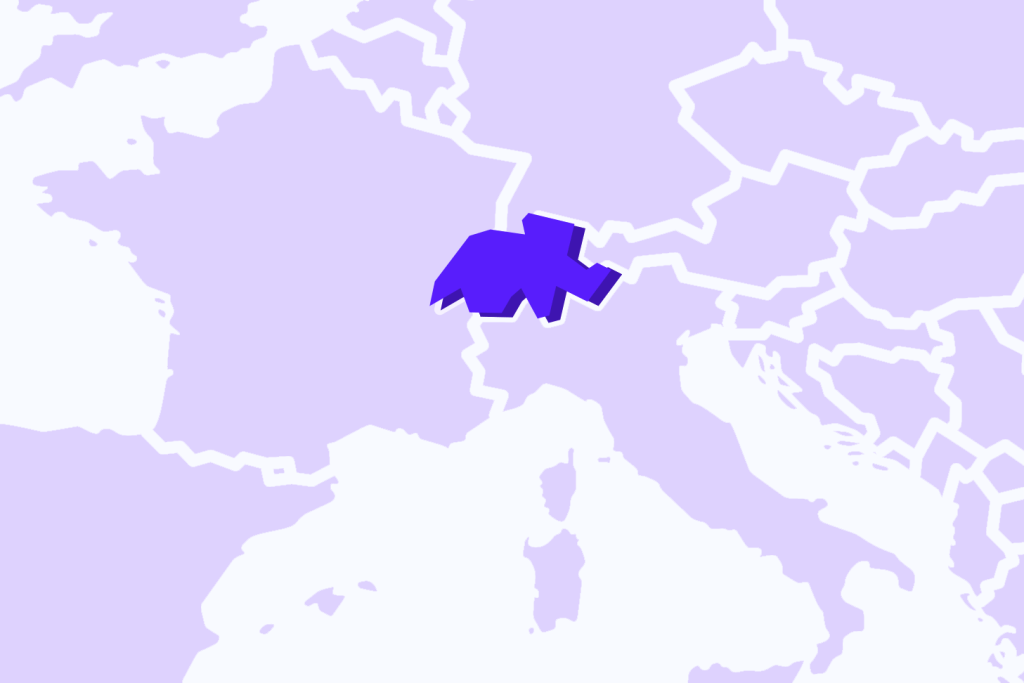

Switzerland is a CRI member.

Malware

In June 2023, research from ThreatFabric highlighted that the Android banking Trojan Anatsa, a dropper malware campaign, had been hitting global banking applications for months, specifically targeting the German speaking region of Europe, including Switzerland. The dropper disguises itself inside other programs, and when clicked on, installs and infects the device. In mid-2023 Switzerland ranked seventh amongst countries most frequently targeted by the malware.

ThreatFabric, which has been monitoring Anatsa since 2020, says it has seen multiple changes in Anatsa’s activity and areas of interest, with continuous updates of targets. The dropper delivering Anatsa was first identified by ThreatFabric researchers on the Google Play Store in March 2023. It was removed by the company, but threat actors quickly replaced it with another application.

Notable regulatory actions and fines

- June 2024: FINMA proceedings against HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA held that the bank violated money-laundering regulations. FINMA imposed measures to ensure the bank’s compliance with its AML rules. The decision limited the bank’s ability to enter into any new business relationships with politically exposed persons until the measures imposed have been implemented in full.

- May 2024: Switzerland’s finance ministry fined UBS bank SFr 50,000 ($55,220) after employees allegedly failed to report red flags of money laundering over a period of several years.

- July 2023: UBS agreed to pay US and UK banking regulators approximately $390m in fines related its involvement with the investment firm Archegos Capital Management, whose collapse had a detrimental impact on Credit Suisse, a rival it acquired earlier in 2023.

- February 2023: FINMA concluded proceedings against Credit Suisse in connection with the collapse of Greensill Capital. FINMA found that Credit Suisse seriously breached its supervisory obligations with regard to risk management and appropriate organizational structures. FINMA ordered remedial measures including:

- periodical reviews at executive board level of the most important business relationships (approximately 500) with a particular focus on counterparty risks; and

- the recording and documenting of the responsibilities of approximately 600 of its most senior employees.

The materials on the GRIP website are for general information purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. While reasonable care is taken to ensure accuracy, the materials may not reflect the most current legal developments. Always consult a qualified lawyer for specific legal matters.