Operational resilience has been a running regulatory theme in 2022, and UK regulators have closed out the year with a bang – issuing TSB Bank Plc with a £48m ($59m) fine for operational risk management and governance failings.

The enforcement from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), pertains to TSB’s seismic outage in 2018 and serves as a chilling example of the damage done when operational resilience is overlooked.

What happened?

In 2015, TSB was acquired by Spanish financial services company, Sabadell. As part of its transition away from its previous owner, Lloyds Banking Group, TSB embarked on a data migration mission of mammoth proportion. TSB laid foundations to move 1.3 billion customer records from its old system to a new one.

The plans for this migration begun in 2015 and continued for three years. A subsidiary of Sabadell, SABIS Spain, was to carry out the lion’s share of the transition.

While the migration was planned over a number of years, it all came to a head on the weekend of April 20-22, 2018 in which TSB undertook the “Main Migration Event” (MME) in which the systems were switched. While the data migration was successful, the new platform experienced technical failures and outages to TSB’s banking services, which trickled down to affect all bank branches and the majority of TSB customers – leaving many locked out of their accounts or unable to access funds.

How did the failures occur?

An investigation by both the FCA and the PRA was swiftly instigated, but it is only now, five years later, that we finally understand the cause of TSB’s outages.

While the majority of the system failures related to issues of IT configuration, capacity and coding, the UK regulators uncovered a series of operational resilience and governance failures that had occurred prior to the MME which had “serious negative consequences”. The key operational resilience failures occurred in four areas:

- Testing: TSB’s migration testing didn’t always keep to set timelines, meaning that the project fell behind schedule. Although it had been planned that tests would run sequentially, they ended up running in parallel to meet deadlines. Testing concluded the day before the decision to migrate was taken. As well as time restraints, the scope of some tests, including how many users could log in to the mobile banking app at one time, had been reduced in scope and so did not cover the gamut of possibility. Had these tests occurred, the FCA and PRA found it likely that some problems would have been detected and therefore remedied.

- Risk management: TSB’s identification of risks didn’t address those that arose from its outsourcing arrangements with SABIS. SABIS had “no experience of managing service delivery from a large number of UK subcontractors”. Moreover, TSB had limited experience of an IT overhaul of this scale and complexity, the risks of which it failed to “explicitly address”. As such, the risks of the project were not fully considered and mitigated.

- Outsourcing: SABIS was TSB’s principal outsourced provider for the IT migration – a service that was critical to the “stability and operation of TSB’s banking services” and therefore “critical to the performance of TSB’s regulated activities”. As such, TSB was required by regulation to take reasonable care and avoid undue operational risk. Despite this, TSB did not conduct a formal, comprehensive due diligence exercise to understand SABIS’s capability to deliver. As well as this, TSB failed to properly assess how SABIS would be delivering the migration project and eventual platform, which involved 85 third parties (TSB’s fourth parties).

- Business continuity planning: When the MME failures occurred, the FCA notes, TCB “quickly found itself in a crisis situation for which it was not prepared”. While it had equipped to manage bumps in the road for the project, it had not considered the full scale of what could happen post-migration. This led to customer frustration and stress for many vulnerable customers who were unable to access or contact TSB after the event, as the volume of calls and complaints had not been considered, among other things.

While TSB took steps to manage the system outages, it did not return to business as usual until December 2018, eight months after the MME.

The regulatory impact

TSB has been ordered to pay a cumulative fine of £48,650,000 ($58.9m), comprised of £29,750,000 ($36.2m) from the FCA and £18,900,000 ($22.9m) from the PRA.

Commenting on the fine, the FCA confirmed that operational resilience is a priority for both regulators and that it is “critically important that firms invest in their resilience”.

Mark Steward, FCA Executive Director of Enforcement and Market Oversight, added that: “The firm failed to plan for the IT migration properly, the governance of the project was insufficiently robust and the firm failed to take reasonable care to organize and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management systems.”

Three key takeaways

Given the swathe of new and emerging regulation in 2022, the regulators’ focus on operational resilience is of little surprise, though this is the certainly the largest operational resilience-focused fine we’ve seen in some time. Away from the everyday focus on operational resilience, there appear to be three alternative and key takeaways for the compliance folk, or indeed any person involved in the onboarding of third-party vendors for projects:

1. What is the experience and ability of your new vendor?

At a recent industry event, a participant asked whether the financial stability of a third party should be considered within operational resilience conversations. The answer was a resounding yes. In the case of TSB, this is extended further to consider what experience and ability your third-party vendor has. When onboarding, you should ask:

- Have you completed a project of this scale before?

- Do you have the tools and documentation to show that you are able to complete the project?

- How established is your platform?

In TSB’s instance, SABIS had “no experience” of conducting IT and data migration on this “unprecedented scale”. Moreover, it endeavored to migrate on an entirely new platform. TSB proceeded with the migration in the willful absence of sufficient documentation, and failed to reassess SABIS’s ability to deliver the migration following a string of issues that had been encountered.

2. Do you have oversight of fourth parties?

Another theme at the industry event was the idea of a net of a third parties. If you hire a third party to carry out a service, do you have to consider the fourth parties that your third party uses to deliver it? The FCA and PRA decision appears to confirm the answer – yes, if they are providing critical services.

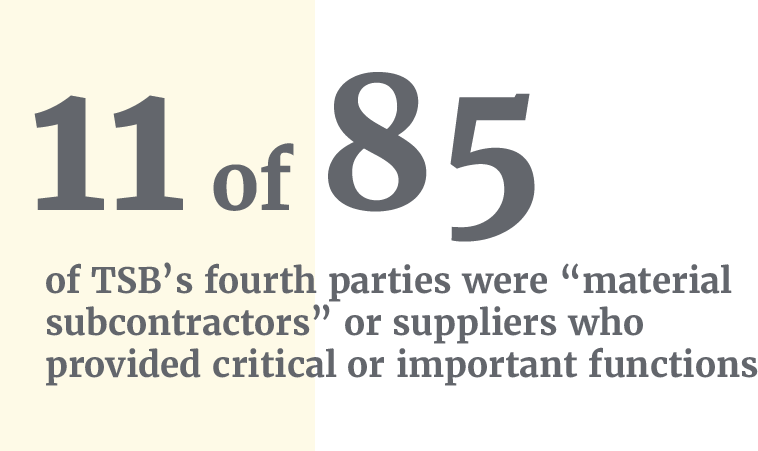

Throughout TSB’s migration, SABIS had “relied extensively on third parties – which were TSB’s fourth parties – to deliver the systems and services required for the migration and its operation”. TSB would in fact obtain the services of 85 fourth parties, 11 of which were “material subcontractors” or suppliers who provided critical or important functions.

The FCA said that, while TSB did not have a contractual relationship with these fourth parties, it “retained responsibility for its obligations under the regulatory system” when outsourcing critical or important operational functions. Because of the lack of contractual relationship between TSB and fourth parties, the FCA found that TSB had been “exposed to significant operational and regulatory risk”.

Regulators expect firms to be cognizant of any risk where it relates to critical business operations, whether that comes from a third party, a fourth or a fifth. The greater your web of third parties, the greater the risk, and the lesser your chance of easy damage mitigation in the event of an outage.

3. Damage is more than skin deep, it’s reputational as well as financial

As well as paying nearly £49m ($59m) in customer fees, TSB also paid nearly £33m ($40m) in redress for distress and inconvenience, customer expenses and putting the customer back in the right position. As well as this, The Guardian reports that TSB paid a further £336m ($407m) to rebuild its internal systems. However, while the monetary fallout has been seismic, TSB also suffered sustained reputational damage which it is yet to recover from. Here lies the truth about operational resilience: sometimes it’s easier to overlook it, but where things go wrong it’s far harder to recover. As the adage goes, fail to plan – plan to fail.