Fines and penalties of almost $30m have been imposed on Metropolitan Commercial Bank (MCB) after failures in risk-management processes led to a huge fraud involving $300m of pandemic unemployment benefits.

“During the pandemic, scammers used sophisticated tactics to take advantage of vulnerable New Yorkers at a time when institutions should have been most vigilant,” said Superintendent Adrienne Harris of New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS). “MCB failed to prevent a massive, ongoing fraud in the MovoCash prepaid card program, allowing bad actors to abuse the financial system.”

There are lessons to be learned from what is a classic case of foot-dragging and not escalating concerns in any meaningful way from an investigative, remediation and basic third-party oversight perspective. And, as the state regulator suggests, not paying any mind to its guidance documents, which the agency offers as essential training tools.

“Third-party fraud ballooned rapidly under these pandemic-era programs, creating oversight challenges for banks.”

MCB

Last Thursday, Metropolitan Bank Holding Corp., the holding company for Metropolitan Commercial Bank (MCB), entered into consent orders with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (the Board) and NYDFS – the state supervisor of Metropolitan – to resolve concerns related to the bank’s relationship with a program manager that processed government stimulus funds and expanded unemployment insurance benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic and was a target of fraud.

Specifically, the consent order resolves NYDFS’s investigation into MCB’s oversight of its MovoCash Digital Prepaid Visa Card Program, which found that the bank failed to maintain an effective and compliant anti-money-laundering program and conducted its banking business in an unsafe and unsound manner.

The NYDFS assessed $15m in penalties, and the Board fined it approximately $14.5m, citing violations of customer identification rules and deficient third-party risk management practices relating to the bank’s issuance of prepaid card accounts.

Fraudulent account openings

In 2020, MCB opened prepaid card accounts for illicit actors who went on to use the accounts to collect illegally-obtained state unemployment insurance benefits. By opening prepaid card accounts through a third-party program manager without having adequate procedures for verifying each applicant’s true identity, MCB violated customer identification rules of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and its concurrent anti-money-laundering (AML) requirements, the agencies said.

The fraud worsened in late March 2020 with the passage of the CARES Act, which expanded unemployment insurance for millions of Americans. As a result of the readily available benefits, the bank observed a surge of fraudulent MovoCash account openings, and after failing to remedy the problem, allowed new MovoCash accounts to be opened.

“This inaction allowed the fraud to increase exponentially over the next few months and facilitated more than $300m in pandemic unemployment benefits to be misdirected to the MovoCash accounts of fraud actors,” the NYDFS said in its order.

What MCB must put right

Within 90 days of this consent order’s effective date, MCB must submit a detailed, written description of all elements of its current program to supervise its third-party program managers to the NYDFS for review.

And in the same time period, MCB must submit a status report that is acceptable to NYDFS with updates on any changes to the Bank’s BSA/AML compliance program that are planned or underway, or have been implemented, plus any ongoing or planned changes to its customer identification program, in connection with its oversight of third-party program managers of MCB’s prepaid debit card program.

MCB must also submit a status report acceptable to the NYDFS on updates it makes to its sustainable governance framework in connection with its oversight of third-party program managers of its prepaid debit card programs that, at a minimum, addresses:

- actions the bank has undertaken and will continue to undertake to maintain effective control over, and oversight of, its management’s compliance with BSA/AML requirements and relevant state laws and regulations;

- clearly defined roles, responsibilities, and accountability regarding compliance with BSA/AML requirements and state laws and regulations for MCB’s respective management, compliance personnel, and internal audit staff;

- measures to ensure BSA/AML issues are appropriately tracked, escalated, and reviewed by MCB’s senior management;

- measures to ensure that the person or groups at MCB charged with the responsibility of overseeing the bank’s compliance with BSA/AML requirements and relevant state laws and regulations possess appropriate subject matter expertise and are actively involved in carrying out such responsibilities;

- adequate resources to ensure the bank’s compliance with the order, BSA/AML requirements, and state laws and regulations;

- and an appropriate and effective reporting structure that permits the Bank’s BSA/AML compliance officer to report information in a timely and complete manner to MCB.

Every six months from the effective date of the consent order and for a period of two years, the bank must submit to NYDFS written progress reports detailing the form, manner, and anticipated completion date of all actions taken to secure compliance with the provisions of the order. This time period could be reduced or extended, NYDFS said.

For its part, the Board is requiring Metropolitan to improve its customer identification, customer due diligence, and third-party risk management programs.

MCB’s response

MCB issued a statement in response to the consent orders and addressing the ample cooperation it provided both agencies – which the NYDFS and Board detail in their respective orders.

“The Consent Orders relate to a unique challenge that arose for a short period at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. MCB was committed to supporting the government’s provision of stimulus funds and expanded unemployment insurance benefits to millions of Americans, particularly underserved consumers who did not have traditional bank accounts.”

“At the same time, as federal and state authorities have acknowledged, third-party fraud ballooned rapidly under these pandemic-era programs, creating oversight challenges for banks. We appreciate that the Federal Reserve and New York Department of Financial Services have acknowledged the actions and enhancements we voluntarily undertook, including terminating the relationship with the third-party program manager at issue in August 2020, and supplementing our oversight mechanisms,” the bank said.

What we can learn

The NYDFS order offers a particularly useful checklist for BSA/AML compliance program directors and their staff (see “What MCB must put right” above). It notes specifically that senior compliance officers learned from a third-party vendor (MovoCash) of transactions suggestive of money laundering or other illicit activity but, instead of investigating the matter and verifying remedial were taken immediately, they merely relied on MovoCash’s assertions saying as much.

NYDFS even points to its own guidance, issued in March 2020, that should have put the bank on notice that it needed to be on heightened alert for fraud in connection with the then-emerging COVID-19 pandemic.

And it observes that, following enactment of the CARES Act, the agency proactively called for heightened caution and monitoring among its regulated entities, which senior executives at the bank failed to appreciate.

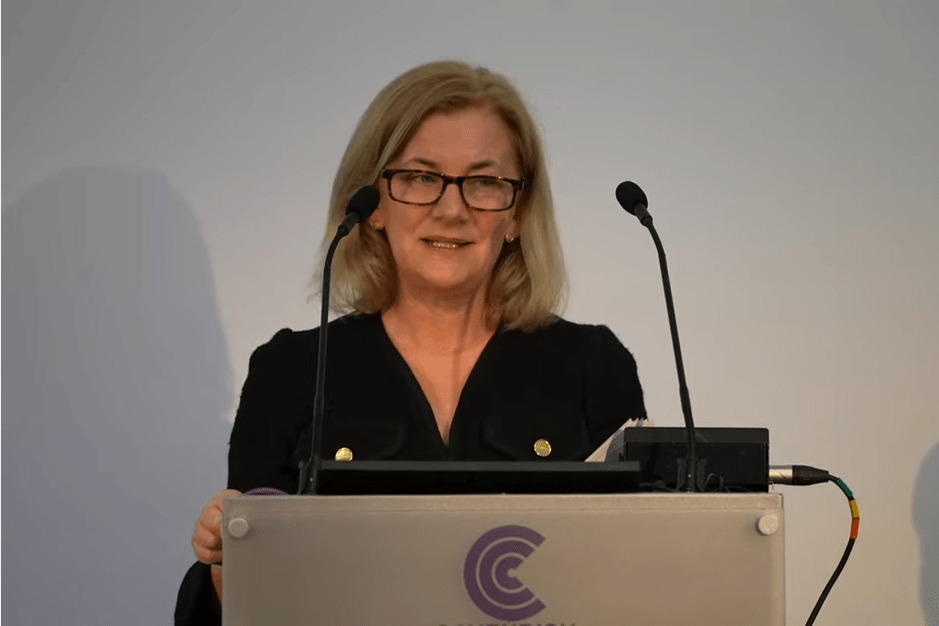

“During the pandemic, scammers used sophisticated tactics to take advantage of vulnerable New Yorkers at a time when institutions should have been most vigilant.”

Adrienne Harris, Superintendent, NYDFS

In its order, NYDFS notes that compliance personnel at MCB observed that they were experiencing significantly more fraudulent account openings in connection with the MovoCash program than with any other third-party program manager.

In a March 2020 email concerning historic MovoCash transaction activity, a compliance officer noted that MovoCash’s explanation of why some accounts appeared to only attempt wire transfer money orders was that it was “most likely because organized fraud/crime groups identified a way to use MovoCash cards for this purpose”.

Right after the CARES Act went into effect, MCB received an increasing number of complaints from consumers relating to fraudulent MovoCash accounts that had been opened in their name. Although the number of complaints abated after a month or so, it was evident that weak controls at MovoCash were continuing to create substantial fraud problems in connection with the MovoCash prepaid accounts. Senior executives at MCB discussed the possibility of terminating the relationship with MovoCash, but the bank chose not to do so at that time, and, instead, continued to allow new accounts to be opened.

Federal law enforcement

Dragging its heels, the bank merely asked that MovoCash institute heightened controls to prevent fraudulent account openings and identify and block fraudulent account, seemingly accepting the fact that, in return, the remedial measures MovoCash took were not sufficient. At this point, federal law enforcement stepped in to tell MCB what it already knew – unemployment fraud was being facilitated by MovoCash accounts managed by the bank. It still took another month for the bank to stop MovoCash from opening new accounts on its behalf.

Inadequate internal controls – specifically surrounding the tracking, escalation, and review of suspected BSA/AML compliance issues – and an ineffective mechanism for those in compliance to report their concerns and have their concerns acted upon in any timely way directly led to these enforcement actions.

in addition, given the increased attention being paid to timely self-reporting by the Department of Justice, Securities and Exchange Commission and, really, all regulators at this point, it is not surprising that a main focus of the NYDFS’s order revolved around the lack of reporting to the Superintendent immediately upon discovering the fraud.

With changes to policies, procedures and internal controls businesses can avoid imperiling the safety of client funds, the issue at the center of the consent orders here. Perhaps the most important changes would be alterations to a compliance culture that values decisive action, vendor compliance verification, clear escalation protocols, and prompt reporting over considerations of expediency.