The UK PRA has published a ‘near-final’ policy statement on the implementation of Basel 3.1 standards. Having taken “account of feedback received” it has made “material changes” to its original proposals lowering capital requirements for:

- small and medium enterprise exposures;

- infrastructure exposures; and

- trade finance-related activities.

In addition it is putting forward:

- A simpler and more risk-sensitive approach to the valuation of residential property; and

- An approach to calculating the output floor more closely aligned with standardized approaches used by firms.

According to the PRA’s estimates “Tier 1 capital requirements for major UK firms will be virtually unchanged” increasing by less than 1% from January 2030.

The PRA asserts that the revised policy statement will “deliver a better balanced and risk-sensitive approach to calculating regulatory capital” and also “support financial and economic stability, and the growth and competitiveness of the UK, while remaining aligned to international standards.”

This last point seems a key one given that the PRA’s announcement comes only two days after a similar about-face by the US Federal Reserve Board, which has also significantly reduced its ambitious proposals for bolstering bank’s capital.

The proposals followed swiftly on the unexpected bank failures in the US involving Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Banks.

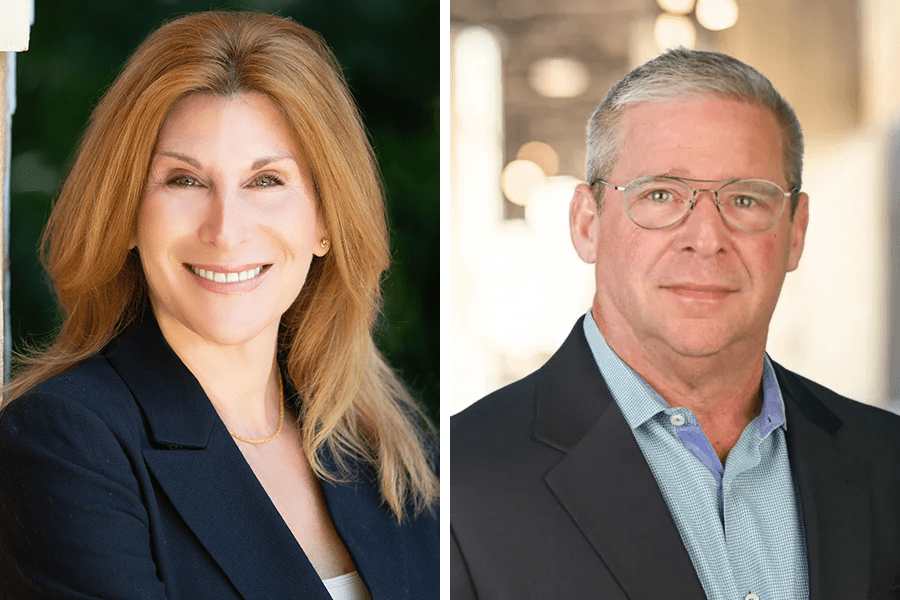

Mixed reactions

Reactions to the UK PRA’s latest decision on capital requirements for banks have been mixed. The bank itself, plus the Labour government, has defended the move.

Sam Woods, Deputy Governor of Prudential Regulation and CEO of the PRA, said: “These rules will improve the way in which we regulate the banks in order to maintain safety and soundness and wider financial stability”, according to a press release by the Bank of England.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves also backed the decision during a meeting with bank bosses after the PRA’s announcement on Thursday. She said: “Britain’s banks have a vital role to play in helping businesses to grow, getting infrastructure built and supporting ordinary people’s finances. These reforms will strengthen the resilience of our banking system and deliver the certainty banks need to finance investment and growth in the UK”, according to reports.

There was also support from the banks, with Barclays Chief Executive C S Venkatakrishnan calling it a positive step forward. But he added he wanted to see more details on how the decision fitted with the broader capital regime, as reported by the Financial Times.

But some experts have warned backing off from the Basel rules could encourage banks to take more risks, which in return could pave the way for another crisis. Bruegel Institute’s Nikolas Veron has told the Financial Times: “Such episodes have not ended well in the past.”

“The time it takes for things to end badly varies of course, but it has to be a concern to anyone watching what is going on,” he has added.

Lobby effect

Global Relay’s Director of Regulatory Intelligence, Rob Mason, believes that strong lobbying by financial firms around the globe seems to have worked. He thinks pressure from the industry is one of the reasons politicians and regulators have backed off from their original plans to introduce tougher rules.

“Concerns are around losing favour with financial services which is a major tax contributing sector in all jurisdictions. Perhaps banks were threatening to reduce employment in some regions if the requirements remained,” Mason told GRIP.

And, as further proof of the heavy lobbying by industry on both sides of the Atlantic, Michael Barr, Vice Chair for Supervision, has acknowledged the receipt of “a great number of comments” on the initial proposals.

According to Barr the feedback received, along with further analysis and discussions held with the FDIC and OCC, resulted in “broad and material changes” to the initial regulatory thrust.

The Fed has decided to increase tier 1 capital requirements for what it terms globally systemically important banks by 9%. This represents a significant concession on the 16% aggregate increase proposed last year. The banks have been lobbying for changes to the original proposals since they were originally published.

Tougher requirements

Under the original proposals tougher requirements were to be implemented for any banks holding over $100bn in assets, but banks with assets between $100bn and $250bn will now “no longer be subject to the endgame changes”.

For these large banks the increases resulting from the proposal would be a modest 0.5% in addition to an estimated 3-4% increase stemming “from the inclusion of unrealized gain and losses on their securities in regulatory capital”.

Credit risk and operational risk requirements of the original proposals would still apply to banks with assets between $250bn and $700bn that are also not G-SIBs or internationally active.

However, for these firms, the market risk and credit valuation adjustment (CVA) frameworks would only apply to firms that engage in “significant trading activity” and the current, simpler definition of capital (numerator in the capital ratio) would apply. The exception to this would be the requirement to reflect some unrealized losses and gains.

In a further concession to smaller firms, the proposed credit and operational risk frameworks would not apply to banks with assets between $100 and $250 billion and they would also be able to use the simpler definition of capital.

The Fed’s re-proposal also includes some additional key changes in the areas of:

- Credit risk

- Reduction in the risk weighting for residential real estate and retail exposures. Extension of the reduced risk weight to regulated entities, including pension funds, certain mutual funds and foreign equivalents

- Elimination of the minimum haircut for securities financing transactions to allow time for the emergence of an international consensus in this area

- Equity exposures

- Lowering the risk weight for tax credit equity funding structures to reflect their inherent low risk.

- Operational risk charge no longer based on a firm’s operational history. Calculating contribution to the operational risk capital requirements on a net income basis rather than on gross revenues.

- Reducing operational risk capital requirements for investment management activities to reflect their meaningfully lower operational losses in comparison with other business lines.

- Market risk and derivatives

- Facilitating banks’ ability to use internal models for market risk including a multiyear implementation period for profit and loss attribution tests.

- Clarifying that uniform mortgage-backed securities positions would be treated as having a single obligor.

- Reducing the capital required for the client-facing leg of a client-cleared derivative to reflect the fact that these are highly collateralized and subject to netting and daily margin requirements.

Finally, in connection with the G-SIB surcharge:

- The proposed capital requirements associated with client clearing will be dropped in order to avoid disincentives for this activity.

- The calculation of the surcharge will be improved and will account for effects from inflation and economic growth when measuring the systemic risk profile of these institutions.

Unlike the PRA’s document, to which no further changes are expected, Barr stressed that the re-proposal is “an interim step”, that none of the regulatory agencies “have made final decisions on any aspect of the re-proposal and that they are open to public comments on any aspect of the re-proposal.

According to Michael Barr these changes will “bring the proposals broadly in line with what the other major jurisdictions are doing … In all of our work, we will continue to seek an approach that helps to ensure financial system resiliency and supports the flow of credit to households and businesses.”

The reference to “other major jurisdictions” is an interesting echo of the PRA’s own comments on its watered-down proposals. The EU deferred its own approach to Basel 3.1 in its fundamental review of the trading book to at least January 2026. The EU Commissioner at the time of the announcement told the FT that the decision was one that was about maintaining “a level playing field.”

GRIP Comment

Many commentators, including the FT, have called the decision by the Fed and other regulators a “capitulation”. This, of course, makes for a good headline, but we don’t really believe that it reflects the reality of the situation.

The sudden collapse of the two banks in California caught the prudential regulators by surprise, and what followed was a knee-jerk reaction that was primarily driven by the memory of accusations of being asleep at the wheel hurled at the regulators following the financial crisis in 2008.

The proposals have since (and perhaps even at the time of being made) been overtaken by worries about macroeconomic conditions. Not only have the banks been successful in putting forward arguments about the potential impact of higher regulatory capital requirements on their ability to support the economy – the regulators themselves have possibly become concerned about their actions being seen as reducing the likelihood of a ‘soft landing’ and potentially being pointed to as a factor in weaker economic growth.

The climb-down can simply be viewed as another example of the continuous ebb and flow between industry and regulator, the one seeking to maximize growth and profitability, the other looking to ensure that the risks being taken in order to do so are adequately considered and that enough money is available to cushion the wider economy from problems in the banking sector.