Fintech companies have become ubiquitous. They offer a variety of services to end-users, ranging from the apps that facilitate savings or payments to those that enable the trading of stocks or crypto.

Some fintechs aspire to challenge the dominant position of the large banks. They expect to be able to do so by leveraging their technological expertise and the absence of legacy systems and processes to outcompete traditional players.

The aspirations of other fintechs are slightly different. Many are niche products that focus on the user experience and interface in order to capture the imagination (and deposits) of potential customers.

New customer segments

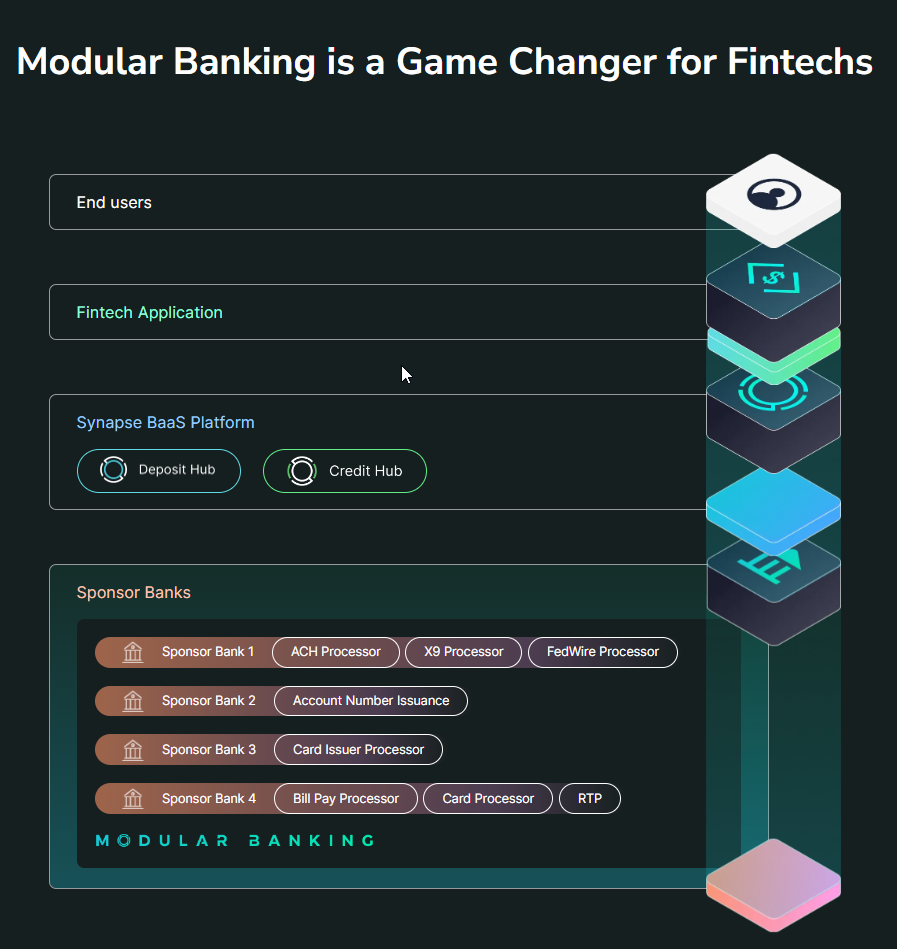

These smaller fintechs, particularly in the early stages of growth, partner with traditional banks in order to enable their services and to accelerate growth in order to satisfy their investors. The banks benefit from this relationship by tapping new customer segments, using the partnership to widen their reach and also to indirectly expand their digital offerings.

Synapse enabled such partnerships by providing critical ledger and reconciliation capabilities, linking the application and user interface developed by the fintech and the relevant sponsor bank.

The firm’s Deposit Hub was touted to fintech clients as something that could “be used for pretty much any application that requires an embedded deposit account” including digital wallets, merchant processing, savings accounts, debit cards and spend cards.

The firm also offered KYC capabilities and delivered all of these to its customers through application programming interfaces (APIs) intended to facilitate efficient contact between system applications.

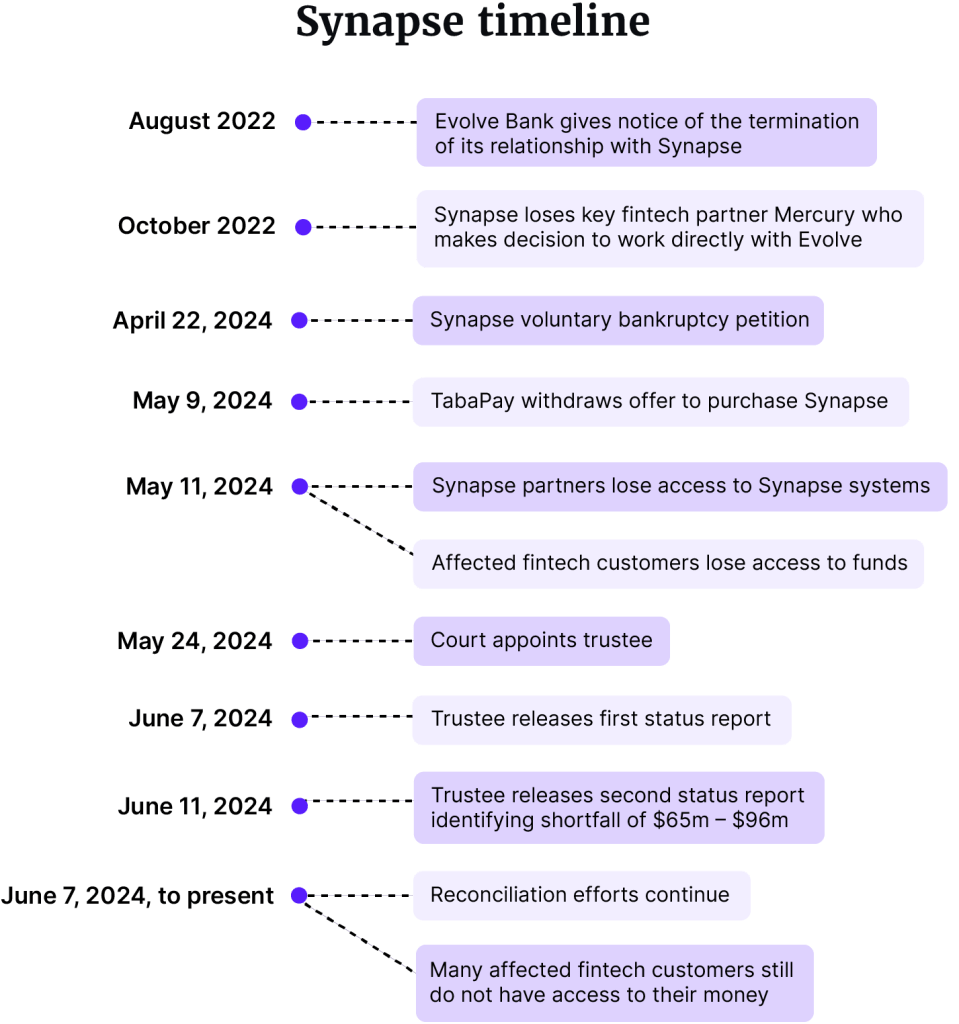

But Synapse filed for bankruptcy in April after a number of key clients, including fintechs Mercury and Dave as well as Evolve Bank, terminated their relationship with the firm last year, questioning the integrity of its systems and processes.

The firm then attempted to sell its assets to another company, TabaPay, as part of a voluntary settlement. The sale was, in part, dependent on Synapse reaching a settlement with Evolve Bank, one of its four partner banks.

A settlement with Evolve Bank was not reached, the sale failed (for this and potentially other reasons – there is a lack of clarity here) and Synapse’s banking partners were allegedly denied access to its systems, forcing them to freeze end user accounts.

This, in turn, led the fintech partners dependent on those banks to lock end users out of their accounts. Relay, Cleo, Dave, Yotta, Stilt, Cooper, Mainvest and Juno Finance were all affected. At least one of these, Mainvest, has ceased operations entirely.

For end users or customers – many of whom believed that their money was safe because the fintechs they were using had a relationship with FDIC-insured banks – it has been a deeply painful experience. And it is entirely possible that some, at least, will not see their money again.

Funding shortfall

The bankruptcy court has appointed Jelena McWilliams, formerly the FDIC Chair, as trustee in the case. The report that she has most recently produced for the court suggests that while reconciliation efforts continue there still appears to be a shortfall of funds ranging between $65m to $96m.

At this point, because of the continuing difficulties in reconciling the balances held by the banks with the Synapse ledger, it is not clear what has caused the significant fund shortfall. According to the trustee report a full reconciliation is likely going to “take weeks to complete” and may, at the least, “delay the repayment of funds.”

Those fintechs and their customers whose funds were held in demand deposit accounts have been lucky in that most of these funds have now been returned.

However, the money of many users was pooled into custodial “for benefit of” (FBO) accounts held in the name of Synapse or Synapse Brokerage rather than in the names of individual clients.

As a result the banks depend on access to Synapse’s systems in order to identify the user funds that they actually hold. Access to these Synapse databases was not initially possible due to the absence of employees (all of whom had their contracts terminated when the business collapsed) as well as lack of access to the ledger record database held in a Synapse AWS environment.

It is in connection with these funds that there appear to be discrepancies leading to the shortfall in funding.

This all exposes significant vulnerabilities within the fintech or banking as a service (BaaS) sector.

The banks in question are all FDIC and OCC regulated and have been working diligently to get money back to users. However, the complexity in unwinding the deposits is such that the trustee has called on the Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC to “make consumer protection staff and other resources available to the public to help end-users understand which Partner Bank holds their deposits.”

Synapse itself, putting aside the complexities of the bankruptcy proceedings and its connection to Synapse Brokerage, is ultimately a technology company that falls entirely outside the regulatory framework. But Synapse Brokerage (not Synapse itself) is both a FINRA member and an SEC-regulated firm and the trustee has made a similar call for resources and support from both agencies.

Complicating matters further is the fact that Synapse Brokerage is not in bankruptcy itself and the trustee has been forced to admit that she does not “have legal authority to directly manage the businesses of Synapse Brokerage as Chapter 11 Trustee for Synapse.” This despite the fact that both “shared employees, functions and systems” and despite the fact that the brokerage “does not have any remaining employees who could interpret Synapse or Synapse Brokerage ledgers to assist in the reconciliation efforts.”

All this exposes significant vulnerabilities within the fintech or as some like to call it the banking as a service (BaaS) sector. The reliance on third-party services to connect fintech entities trying to scale and traditional banks whose experience and ability to deal with novel technologies is often in question has created a fragile dependency on external partners over which both parties have only very limited control.

Although not reported widely, the number of consumers affected – coupled with the lack of a swift resolution to the problems and the potential for money loss – means that trust in this fintech ecosystem may well be eroded going forward.

GRIP Comment

Reliance on third party providers has become commonplace because technology has made it both possible and efficient to connect disparate systems. Vendors can bring hugely valuable specialist expertise and tools to bear on operational problems of large organizations – they often represent an efficient and effective solution to problems that non-specialist teams struggle with.

But many organizations understand their reliance on third parties only imperfectly and often overlook the risks that these represent to their core operations.

A key lesson from the Synapse debacle is the fact that dependency and vulnerability mapping is critical, as is the need to have in place robust recovery or back-up processes and systems for critical functions. Stronger safeguards around technology alongside contingency planning to protect customers and end-users is key.

Lessons learned for firms from this case could be summarized as follows:

- Review all third-party partnerships along with their relevant safeguards and contingency plans.

- Conduct robust due diligence – a thorough vetting of third-party service providers should not be a one-off exercise.

- Do not underestimate the potentially devastating impact of technology failure.

- Operational resilience is critical.

Because Synapse is not a regulated entity, it is not entirely clear who will pick up the pieces here in terms of a regulatory response.

And so perhaps there is a lesson for regulators in this saga as well. In an increasingly interdependent world it is essential to hold regulated firms to account for their technology and architectural decisions. The other option is regulating the ecosystem as a whole and given its exponential growth it is unlikely that even the most ambitious of regulators will want to engage in that truly herculean effort.