A changing political landscape will invariably affect critical areas of regulation such as artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, supply chains, financial crime oversight, recordkeeping and overall risk governance. But maybe not as much as you suspect.

That’s thanks to some broadly accepted expectations of what constitutes strong markets and investor protection in specific areas, and businesses today being expected to care about such wider considerations as national security interests, human rights and technology safeguards.

Artificial intelligence

Businesses are creating sandboxes for controlled experiments, seeking buy-in from key executives, and trying to carve out an adequate budget for testing and developing their artificial intelligence (AI) tools. Regulatory agencies and other government entities are reminding them about their compliance responsibilities in this space, noting the fraudulent misuse, bias, misinformation, hallucination potential of the tools, and the need for diligent oversight over them.

This will likely be the state of affairs for a long time, regardless of whether specific government initiatives get a name change or small revisions, as many influential people with expressly different political leanings in the tech and regulatory sectors have expressed the same mix of high hopes and deep concerns regarding the technology.

In September, the Department of Justice updated its guidance on the Evaluation of Corporation Compliance Programs to include questions specifically focused on companies’ use and implementation of artificial intelligence, such as how companies are integrating such new technologies into broader enterprise risk management ones.

The SEC has brought a small number of AI-related enforcement cases, largely related to the allegedly misleading statements about their AI tools’ capabilities, charging them with what has been labeled “AI-washing.” The regulator in March fined two investment advisers, Delphia (USA) and Global Predictions, for allegedly doing just that.

And the agency’s Examinations Division recently released its 2025 priorities, which reminded advisers that if they integrate AI into advisory operations, including portfolio management, trading, marketing, and compliance, their SEC examination could feature an in-depth look at compliance policies and procedures, as well as any public statements or disclosures to investors.

The general trend of legal and regulatory authorities being mindful of the need for strong governance in this area will likely linger.

As the priorities document mentions, digital investment advisory services and “gamified” recommendations are a big concern, and that worry is shared across political divides when it comes to retail investors and the more vulnerable members of that population.

FINRA has issued guidance on the use of generative AI by broker-dealers specifically, reminding firms that FINRA’s rulebook is technology-neutral, that SEC regulations for broker-dealers continue to apply to AI and that FINRA rules apply to AI developed in-house by broker-dealers and ones provided by third-parties.

It would be unwise to discount the SEC’s, FINRA’s, or any other federal agencies’ use of existing regulatory provisions to bring enforcement actions in this space. As former SEC Enforcement Director Gurbir Grewal said about one SEC case in this arena: “It’s an old school fraud using new school buzzwords.”

The White House has issued executive orders and memoranda on the importance of businesses using the technology with the appropriate testing, monitoring and other safeguards – and warning of misuses that could threaten US national security or facilitate human rights abuses.

Again, even if the executive branch stops doing this so publicly and independent agencies are merely encouraged to use existing powers to do the same, the general trend of legal and regulatory authorities being mindful of the need for strong governance in this area will likely linger.

Geopolitical tension and supply chain disruption

The potential for the Israel-Hezbollah conflict to spill into regional war has been increasing since Israel launched a series of withering and sophisticated strikes against the Iran-backed Lebanese paramilitary group.

These simmering geopolitical risks have market participants worried. Oil prices have taken a dramatic uptick as production and distribution confidence waver, and the price of gold has reached dizzying new heights as investors seek a safe haven from market chaos.

Intangible assets such as Bitcoin have also seen price rises, although this is partially connected to popular faith in Trump’s election chances and the success of his promised deregulatory efforts.

Supply chains, on the verge of recovery from 2020-21 COVID lockdowns, have become destabilized by Iran-backed Houthi pirates whose incursions in the Red Sea have included brazen strikes against internationally-flagged vessels.

The Guardian has reported that rerouted ships face an added 40% in fuel costs, while container prices have also risen 486% higher since the end of last year. Voyages often now require an additional four weeks as ships are rerouted around the Cape of Good Hope.

The presidential candidates have diverged on their path forward in the Middle East. Harris, while broadly supportive of Israel’s war effort, has signaled that she would pursue the current administration’s plan to mitigate civilian casualties and broker a durable peace. Trump, conversely, is more supportive of Benjamin Netanyahu’s aggressive plan to continue to mount pressure against Hamas and Hezbollah, arguing that making any concessions on humanitarian or de-escalatory grounds would allow the terror groups to regroup and rearm.

US Treasury issued a final rule restricting some types of investment in China, part of a bipartisan effort within the White House and Congress to maintain a US technological edge amid economic competition between the two countries.

Trump’s first term saw him reverse the bulk of the Obama administration’s diplomatic outreach to Iran, and he has made conciliatory gestures to the Chinese and Russian heads of state, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. He also sought to pull the US out of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Even if Trump is persuaded by others that NATO is worth staying in (which is likely to happen again), he will likely put even more pressure on getting Europeans to spend more money on their own security.

He also threatens to impose a 10% tariff on all imports from across the Atlantic, which economists say will likely have its effects on consumers when companies pass those costs along to them.

Sanctions imposed by countries such as the US, EU, UK and Canada that target officials in China over human rights abuses against the mostly Muslim Uyghur minority group in the region of western Xinjiang – plus import bans that restrict imports on entities tied to products associated with the ongoing abuses – are likely to continue in some form, regardless of the election’s outcome. There is strong bipartisan support for these measures.

Geopolitical tension, sanctions and technology meet up at this intersection too: The US Treasury just issued a final rule restricting some types of investment in China, part of a bipartisan effort within the White House and Congress to maintain a US technological edge amid economic competition between the two countries.

This rule prohibits US citizens from making investments in “countries of concern” that relate to sensitive technologies such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors and quantum computers. The Biden administration has so far named China as the sole focus of it, and it’s an initiative likely to be supported by either administration.

Cyber resilience and data beach disclosure

Data breach notification requirements in 2024 consisted of some updates at the federal level, and the year provided some reminders of how important business continuity plans (BCP) are in the cybersecurity arena. Companies more prepared for technical failure, having backups, data recovery mechanisms, testing and drilling, and effective communication and coordination plans fared better.

Let’s start with the rules. On May 2024, the SEC finalized amendments to Regulation S-P, which defines privacy and security requirements for broker dealers, investment companies, registered investment advisers, and transfer agents.

The amendments require covered institutions to implement and maintain written policies and procedures for an incident response program. The program must be reasonably designed to detect, respond to, and recover from unauthorized access to or use of customer information, including specific documentation requirements related to security incidents.

And Reg S-P includes new obligations around customer notification; covered institutions must provide notice to individuals as soon as reasonably practicable but not later than 30 days after becoming aware of the unauthorized access to or use of customer information.

And then there were the cyber events, namely, the CrowdStrike incident. In July, a global IT outage stemming from a faulty CrowdStrike software update revealed the broad risks posed by a single point of failure and the degree to which many segments of the economy are interconnected and interdependent.

Businesses exposed to technology and concentration risk tied to large vendors and ubiquitous systems is a sign of the times and the incident was illustrative of the dangers posed when a single security vendor is deeply embedded within an organization’s infrastructure. Any disruption can have widespread and severe impacts. If the outage had been due to a cyberattack – rather than a technical error – the consequences could have been catastrophic, potentially leading to unauthorized access, data breaches, or ransomware attacks.

The SEC assumes your misleading or otherwise poorly described disclosures about something as important as cybersecurity incidents have resulted from deficient disclosure controls. And it won’t tolerate it.

And then there were the enforcement actions. Most recently, in October, four US companies, Avaya, Unisys, Mimecast and Check Point Software Technologies Ltd were each charged by the SEC for downplaying the extent to which their data had been compromised in the massive 2020-2021 SolarWinds “Sunburst” hack.

Despite losing in court on most counts in its SolarWinds litigation, the SEC was determined to hold those four businesses to account for not sufficiently disclosing a material cybersecurity incident. Mapping its language in its final cybersecurity rule (“Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance and Incident Disclosure”), the SEC said companies cannot minimize a material cybersecurity incident in its public disclosures by describing them in hypothetical or generic terms.

In its order settling charges with one of the companies in that sweep action, CheckPoint Software Technologies, the SEC even admitted that it had found no evidence that any customer data, code or other sensitive information was accessed.

The message here: The SEC assumes your misleading or otherwise poorly described disclosures about something as important as cybersecurity incidents has resulted from deficient disclosure controls. And it won’t tolerate it.

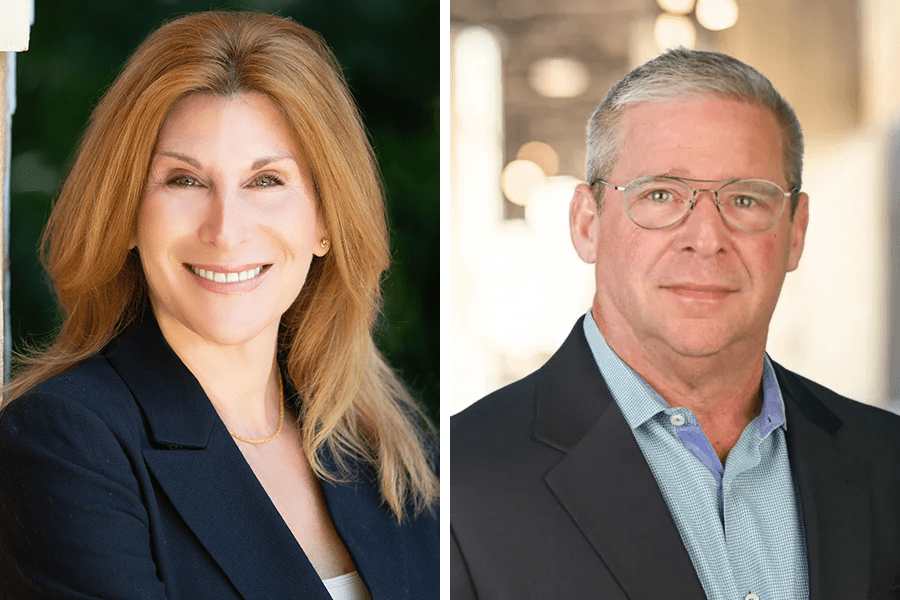

Will the SEC behave the same way in 2025 if it has a new commissioner makeup? Probably not, given Commissioner Hester Peirce’s and Mark Uyeda’s joint dissenting opinion about why they saw the SEC’s orders against the four businesses as a judgment that second-guesses the business’s disclosure while citing “immaterial, undisclosed details to support its charges.”

But what of the lessons learned from CrowdStrike and the lessons imparted about vendor overreliance and the need for BCPs? Those lessons have been laser-imprinted into business’s minds, thanks to the amount of money lost, resources redirected and attention received by that outage’s ripple effects. And there’s no going back.

The SEC under Jay Clayton certainly focused on the adequacy of cybersecurity-focused oversight of third-party vendors and governance practices related to safeguarding customer records and information. Because nothing quite scares an investing public and a national watchdog agency more than critical financial data being compromised or held for ransom by absolutely anyone, US adversaries in particular.

AML and sanctions

These financial crimes will likely stay in the spotlight. Each year seems to usher in at least one monumental enforcement action, and 2024 is no exception. But let’s start with what didn’t happen.

The Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) introduced requirements around beneficial ownership transparency in the US and came into force on January 1. Despite the overwhelming bipartisan effort to increase corporate transparency under US law, an Alabama federal district judge ruled in March that the Treasury Department cannot require small business owners to report details of their owners and others who benefit from the business.

An appeal was filed by the government, and the CTA’s constitutionality is being challenged in court by various states, with the rule in effect in the interim. Other states have passed or are planning to pass into law their own versions of the CTA.

Under the new legislation, businesses that meet certain criteria must submit a Beneficial Ownership Information Report to the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). This report provides details identifying individuals who are associated with the reporting company.

The CTA was established to prevent individuals with malicious intent from hiding or benefitting from the ownership of their US entities to facilitate illegal operations, such as money laundering, terrorist financing, narcotics trafficking and other crimes affecting national security while also being tied to human rights issues.

Since a bipartisan portion of Congress overwhelmingly voted to enact the law, it is unlikely the government will not seek out other avenues (judicial and legislative) to reach these goals.

In July, FinCEN proposed a rule to strengthen and modernize financial institutions’ anti-money-laundering and countering-the-financing-of-terrorism (AML/CFT) programs.

While financial institutions have long maintained AML/CFT programs under existing regulations, the proposed rule would amend those regulations to explicitly require that such programs be effective, risk-based, and reasonably designed, enabling financial institutions to focus their resources and attention in a manner consistent with their risk profiles.

The proposed amendments were based on changes to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) as enacted by another piece of bipartisan legislation – the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 – and are a key component of Treasury’s objective of building a more effective and risk-based AML/CFT regulatory and supervisory regime.

In July, the SEC’s Division of Examinations published a Risk Alert outlining its examination observations about key AML requirements. The SEC said some registrants did not appear to devote sufficient resources, including staffing, to AML compliance in relation to the volume and risks of their business.

Fast forward to October and an extraordinary and groundbreaking case: TD Bank became the largest lender in US history to plead guilty to failures under the Bank Secrecy Act and the first to plead guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering, being assessed a penalty of a little over $3 billion in fines in total.

The bank’s actions allowed drug cartels and other criminals to move hundreds of millions of dollars in illicit finance, said the Department of Justice (DOJ), FinCEN, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve, which each brought charges and assessed fines. (The bank also accepted an asset cap of $434 billion imposed by the OCC.)

The regulators each stressed that TD Bank’s persistent prioritization of growth over controls allowed its employees to break the law and facilitate the laundering of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Early in the year, the New York Department of Financial Services examined cryptocurrency firm Genesis Global Trading twice in routine inspections, the agency said in its press release, and it found AML and cybersecurity failures that the firm addressed with “little effort or resources.” It apparently had no dedicated officer to oversee AML compliance.

It’s not anything anyone would disagree about, which is why this focus on AML compliance adequacy – dedicated expertise, staffing, time spent, technology invested in – is going to persist.

Sanctions compliance looks much the same. In the past 24 months, the US government has raised the stakes in this arena. The Biden administration has expanded the US sanctions and export control regimes and US agencies have adopted a more comprehensive approach to the enforcement of export controls.

Their businesses are so global in nature, are subject to US state rules where they operate, and typically seek to go well beyond rule requirements anyway – all of it adding up to their firms not being likely to make material changes after the electoral votes are tallied.

An expansion of US sanctions among other measures issued during the past several years (especially those targeting Russia in connection with the conflict in Ukraine) have significantly heightened compliance risks and regulatory expectations that, again, resources are being deployed adequately.

Former President Donald Trump’s administration unleashed a whirlwind of economic sanctions on individuals and entities during his single term in the Oval Office. The punitive measures were aimed at squeezing the US’s foes – most notably Iran, Venezuela and China – to advance his foreign policy agenda.

As a candidate, he talks about doing whatever it takes to maintain a competitive edge for US manufacturing, including harnessing a large array of tariffs, and would be likely to continue the trajectory he was on while in office.

And a Harris administration will likely continue the trajectory put forward by President Biden, which has included the DOJ adding many more prosecutors to investigate and prosecute sanctions evasion, export control violations and similar economic crimes and extending the statute of limitations for violations of certain sanctions administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control from five to 10 years.

Recordkeeping obligations for business comms

The institutions fined for recordkeeping failures involving at least some combination of texts, WhatsApp messages, and audio files, if not other communications formats, are not only numerous but were responsible for paying about $3.3 trillion in fines to US regulators since September 2020.

To say this has been a regulatory and enforcement priority for the SEC and CFTC in particular is to put it mildly.

As heard at industry events more recently, regulated businesses are expressing increasing frustration as they strive to deal with this matter successfully. When asked at a conference recently if such firms need to consider this area to be a constant liability, SEC Chair Gary Gensler replied that books and records is, and always has been, incredibly important as a control at firms and it has been since the 1930s.

And the reason why he sees this as a continuing focus area is because the SEC and other regulators have solid evidence that off-channel communication is still taking place widely and being carried out by some of the most senior individuals at regulated firms. Plus, he reminded the audience that piecing together business communications is how some major scandals were unearthed and pieced together, such as the Libor and FX ones.

Whether any new leadership at the SEC believes the focus should remain intact is another matter, especially considering the two names that are being bandied about to take his seat as chair if Trump wins have become critical of the ongoing sweep of fines in this arena – Commissioners Hester Peirce and Mark Uyeda.

But if Gensler remains until the end of his term in spring 2026, this enforcement trend will be a constant compliance liability area.

It might actually be a more accurate statement to say something like a middle ground will be reached, regardless of SEC and CFTC leadership and partisan majorities among their commissioners.

The securities regulator might ease back to an extent, but companies have already invested in the technology – or are exploring such options – training their staff and having conversations involving terms like “lexicons,” and “off-channel” and “archiving,” and it is likely too late to go back and pretend these records are not important ones for everyone involved to preserve. After all, some of these archived messages might someday relieve a company of blame and yield something they can use as a defense to any allegations of wrongdoing.

It’s not the election, it’s the aftermath

At a recent industry conference event, panelists from several financial services firms said this about upcoming US election results: It won’t have a big effect on their large firms. Policies and processes for nearly everything will not change.

They said their businesses are so global in nature, are subject to US state rules where they operate, and cited areas where they typically seek to go well beyond rule requirements – all of it adding up to their firms not being likely to make material changes after the electoral votes are tallied.

Each of them expressed more concern about instability and even a possibly a less-than-peaceful transfer of power following the voting and were monitoring their risk exposure to such an occurrence, especially to any vendor and supply-chain disruptions.