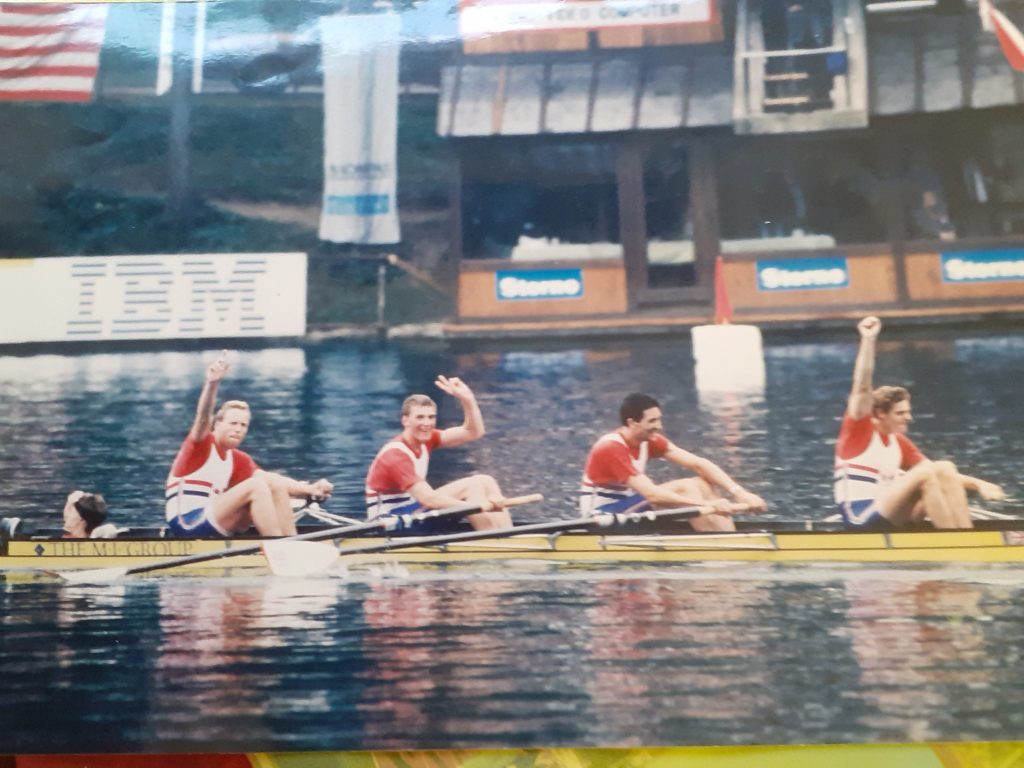

Photo: Private

We spoke to Gavin Stewart, an independent commentator on financial regulation; former regulator; novelist; ex-international rower and sports administrator. He has 27 years’ experience working for financial services’ regulators (Bank of England, FSA and FCA), holding a wide variety of roles including as a Bank of England Supervisor, FSA Head of Strategy, Planning & Performance, and FCA Chief Risk Officer.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

First, I would say “prepare to be surprised”. I’m not sure what expectations I had when I was young, but they were nothing like what happened.

Academically, I was good at humanities’ subjects and was about to go to university to study history, but had topped out on maths at O Level. But I somehow went on to spend 27 years working in financial regulation, which barely existed when I was young and was nowhere on my radar. Meanwhile, in terms of sport, I wasn’t strong, fast, or skilled enough to excel at anything. In fact, always on the clumsy side, I had grown about six inches when I was 17 and my height had just hit 6’8”, so sport was about trying hard and hopefully having fun, interspersed with various humiliating episodes. Yet, through a highly improbable series of events, I found myself rowing for GB at two Olympics.

My second piece of advice would be to “leave yourself open to unexpected friendships”.

When I was young, I assumed my friends would have similar backgrounds and interests to me, but instead they are mostly people I have been thrown together with by circumstance, with the overlap between our backgrounds and interests often minimal. But the importance of shared experiences and what we learnt about each other through them has more than bridged the gaps between our backgrounds and characters.

Lastly, I would advise myself, whenever possible, to “sleep on your big decision”. A couple of examples, one good, the other not so much…

When I was rowing at Oxford University, where I learned the sport, I was involved in what became known as the 1987 Oxford Mutiny – I was one of the bad guys – about which various articles and books, even a film (so accurate, most of us had the names of our characters changed) are available if interested. We ended up winning the Boat Race, but as a young athlete it was pretty fraught and nerve-wracking. A big part of what got me through was that each morning I would calmly rehearse the previous day’s events and revisit what I would do next. Even at the time, it felt vital to detach myself from the passions of the day before.

Later, however, there were times at work, particularly in the early days of the FCA, when I reacted too quickly to a set of events, without assessing the full range of options or some of the more unlikely downside risks. Sometimes, those decisions needed to be made in real time, but many of them would have been better made the morning after.

What has been the proudest moment of your career?

I’ll avoid picking something from regulation, because pride in that context tends to be about not missing something in the external world, or not making a poor decision internally, and so feels too qualified to register here.

Sport is more straightforward. I came out the right side of some close races, but I am conscious they could easily have gone the other way, so instead I’ll choose winning a bronze medal at the 1989 Worlds in what was then, just about, still Yugoslavia. We felt like the maverick crew of the Team but had together built a world class crew in just six weeks together, beating the East German Olympic Champions in the process.

If I may, I would like to add one other moment, a vicarious one from my time on the Board of UK Sport, when I chaired its the Lottery Awards Panel. The Sydney Olympics had just started, and I was doing the laundry at home when Jason Queally won GB’s first Gold medal, in track cycling. I really believed in cycling’s performance plan which, together with sailing, was the most ambitious of all Olympic sports, but worried Sydney had come too soon, and that we would have to defend its funding after the Games. Jason Queally’s victory put those worries to bed.

Tell us an amusing anecdote about your work

I’m not sure how amusing this is, perhaps black humour … Despite talking a lot about prioritizing, regulators often struggle to do it in practice (cf recent NAO report), an understandable wariness given the inevitable accusations when even small things go wrong. One of the “funniest” examples was the ExCo that set out to reduce a long list of +30 priorities to the number 20 at most. In doing so, however, they lost none of the original list, instead rewording the remaining priorities to include everything as a list of 20. Watching the horse trading was darkly amusing.

Can you recommend a good book?

At this particular time, I would probably choose “Lincoln”, Gore Vidal’s inside-the-White House historical novel. When it came out in the mid-1980s, I was still a history student and, as well as its fascinating sub-plots and beautifully rounded imperfect characters, it offered a brilliant insight into US politics and the Civil War.

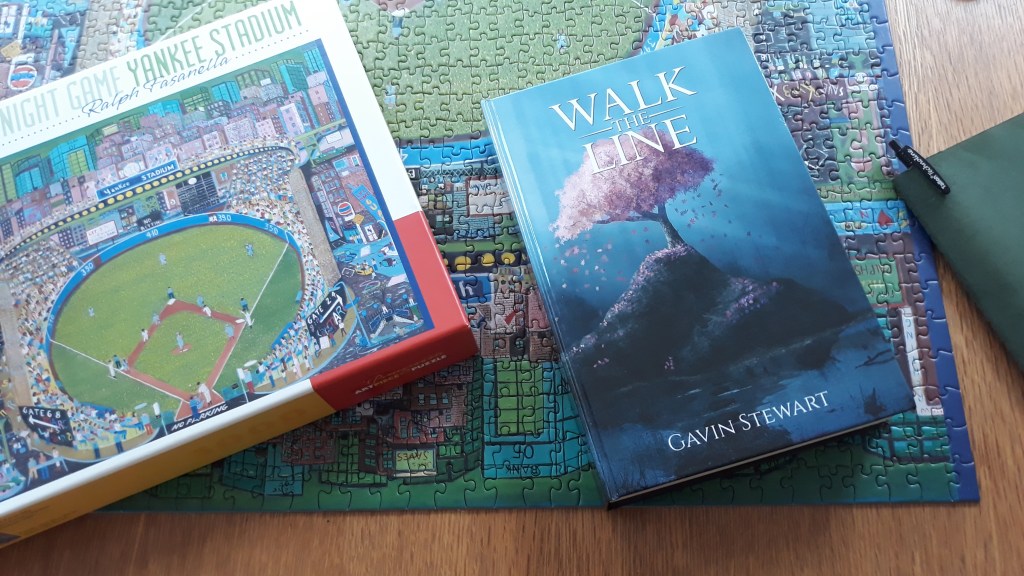

If I may, can I also mention my own novel, Walk the Line which is about how a group of friends and their relationships change over a 40-year period, It jumps randomly back and forth across that period, revolving around the 7/7 London bombings in 2005. My second novel, An Endless Chain, is due out next year.

Give us a prediction for 2024

My prediction would be some sort of major row over the Government’s deregulation agenda and the importance of regulators’ new secondary objective on competitiveness, possibly around crypto, or buy now pay later.

What’s your New Year’s wish?

My wish is that, as a country, we find a way to build more houses. Since the financial crisis, I’ve become increasingly convinced that our failure to do so accentuates a host of regulatory issues, plus some wider problems.

Your resolution for 2024?

My resolution, closer to home, is to be better at keeping in touch with and seeing friends. Too many of them have heard too little from me this year.