26 June, 2024 by Joe Miller in New York and James Kynge in London

In January 2021, US Drug Enforcement Administration agents watched a man drop off a large white bag with “Happy Birthday” written on the side at an office complex in Downey, California. It contained $226,000 in cash.

Three months later they witnessed the same man leave a Fruity Pebbles cereal box full of almost $60,000 in cash at a house in Temple City, California.

The DEA initially thought the cash deliveries were the routine result of the soaring sales of fentanyl in the US. But during the course of their investigation, they suspected the drop-offs were also part of a sophisticated and growing form of illicit finance that involves so-called Chinese underground banks and the Mexican drugs cartels.

In an indictment unveiled in a California court last week that provides an unprecedented insight into the allegedly evolving global network, prosecutors accused Edgar Martinez-Reyes, who was present at the two cash drop-offs, and a group that included nine Chinese nationals of laundering $50mn for the Sinaloa cartel in Mexico.

Martinez-Reyes, a Mexican national who lives in Los Angeles, has pleaded not guilty, as have the other 11 defendants who have so far been arraigned. The case is likely to go to trial.

For the law enforcement agencies grappling with the fentanyl crisis, the indictment represents anything but an isolated incident. They claim the alleged offences are part of a process where over the past decade Chinese organised crime groups have moved in to launder the earnings of the Mexican cartels.

The money laundering groups are made up of networks of Chinese nationals living in the US and Mexico as well as individuals in China. As fentanyl revenues have surged over the past few years, the officials say, their relationship with the Mexican cartels has expanded dramatically.

The underground banks operate largely by selling the cartels’ dollars to wealthy Chinese who, alarmed at the political tightening under Chinese leader Xi Jinping, are looking to circumvent capital controls and transfer their money out of the country.

In essence, the officials claim, a new global money laundering network has evolved that marries two powerful financial forces — the huge stockpiles of cash being accumulated by the Mexican drugs cartels from selling drugs in the US, and the rapidly growing volumes of capital seeking an escape route from China.

“Chinese money launderers have taken over laundering for the Mexican drug cartels,” says Chris Urben, who worked at the DEA for 24 years, investigating traffickers around the world. This alliance, he adds, is “amazing to watch . . . a game-changer”.

In interviews with the Financial Times over the past few months, more than a dozen current and former DEA agents and high-ranking law enforcement officials in the US, UK and Italy have raised the alarm about a method of money laundering that they say is evading standard forms of surveillance and is thwarting their efforts to pursue drug traffickers.

They say that the arrangement is fuelling the fentanyl crisis in US towns and cities, which is killing thousands of Americans each month, while also playing a role in boosting organised crime across Europe.

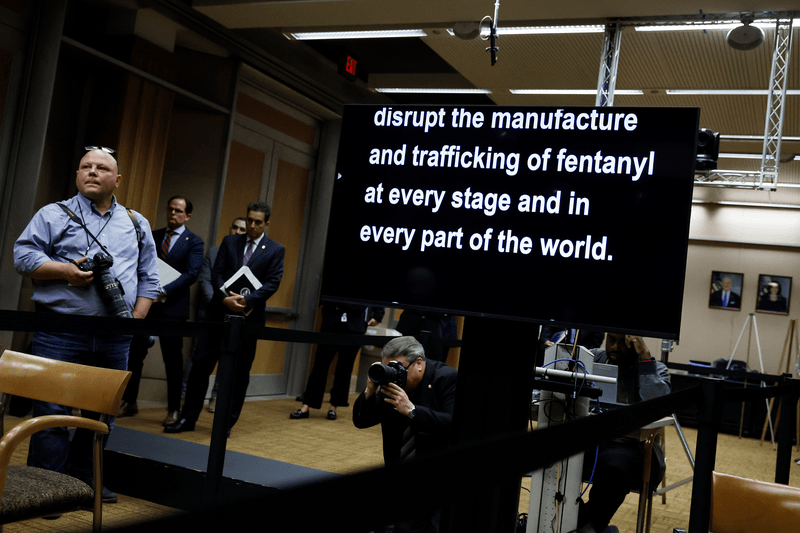

This enterprise is able to “move money faster, cheaper and at a fraction of what is usually charged [by money laundering organisations]”, warned Anne Milgram, head of the DEA, after announcing the indictment which was the result of a co-ordinated sting with authorities in the US, China and Mexico.

The Sinaloa cartel, she added, now “relies on a network of Chinese money launderers to profit from selling drugs across the US”.

Urben, who in 2018 was assigned by the DEA to tackle this emerging threat, says that Chinese organised crime groups in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, who communicate via encrypted Chinese apps such as WeChat, have created an underground banking system that minimises the movement of funds across borders.

In this scheme, “dollars don’t leave the US, pesos don’t leave Mexico, and renminbi does not leave China”, Urben explains. “Encrypted communications [allow] all of this to happen instantly”.

Before Chinese money laundering organisations entered the scene, officials say, Mexican and Colombian gangs could expect to lose roughly 10 per cent of their earnings in the money laundering process. The losses were due to theft, the cost of bribing border security guards, and regular seizures of cash shipments by US law enforcement.

Even the most common form of money laundering used by cartels in recent years — a system sometimes known as the Black Market Peso Exchange — was inefficient. It involved the purchase of goods such as clothing or computers in the US, their delivery to a third-party in Latin America, and the sale of those items to consumers in local currency. Weeks could pass before clean cash was handed back to cartel bosses.

“For years, the Sinaloa cartel relied on smuggling truckloads of cash to Mexico or using middlemen to launder that money through banks and businesses,” Milgram said. Now, she added, it has developed “a new criminal partnership with Chinese nationals living in the US”.

The Chinese groups charge a commission that vastly undercuts what their competitors used to demand — in some cases, officials say, charging one or two cents on the dollar. As Urben puts it, the Chinese groups “beat everyone out of the marketplace”.

While violence is routine at all stages in the drugs trade, Urben says that “not one time have I seen this happen to a Chinese money launderer”. This, he suspects, is because “they offer such a valued service” to the fentanyl traffickers.

California prosecutors involved in the recent indictment said Chinese money laundering groups were able to process “enormous amounts of US currency”, and dispose of drug proceeds by buying property, cars and luxury goods.

“Every money laundering investigation that we have now involves a significant amount of Chinese money launderers inside.”

DEA official

But the most sophisticated element of the alleged laundering scheme they outlined is the same one identified by DEA agents tracking other operations in the US — so-called mirror transfers using Chinese bank accounts that are practically invisible to US authorities.

The process usually begins with Mexican gangs delivering dollars in bulk to Chinese money laundering organisations in the US.

In motels and parking lots across the country, authorities have witnessed cartel members drop off bags of cash to Chinese nationals. These are normally not criminals, but rather students, retail workers or taxi drivers recruited to secure the money who in some cases are not aware of the connection to drug traffickers.

Once the couriers have the cash, they send a verification code through an encrypted app. Upon confirmation of receipt, the Chinese brokers pay the cartels using associates in Mexico, often in pesos.

To clean the cash they have accumulated, the money laundering groups often sell the dollars to wealthy Chinese in the US. In return, these individuals authorise a bank transfer in China of the equivalent amount in renminbi to accounts controlled by the money laundering organisation.

“Every money laundering investigation that we have now involves a significant amount of Chinese money launderers inside,” says a senior DEA official.

The laundered money rapidly makes its way back into the legitimate economy. US authorities say that the cash is sometimes used to buy expensive cars and luxury property across the US, without any alarms being raised.

The FBI has warned that in some cases, Chinese students pay for tuition at US universities with cash that has been laundered. These transactions must be reported to the US Treasury if they involve sums over $10,000, but were not necessarily flagged as suspicious by the department, DEA officials said.

The US Treasury said it supported law enforcement agencies “with critical insights and protected access to the millions of reports filed by financial institutions pursuant to the Bank Secrecy Act”.

While the scale of the new money laundering system has alarmed law enforcement, the networks involving Chinese groups have been on their radar for a number of years.

One of the first to spot the involvement of Chinese organised crime groups in the drugs trade was Ray Donovan, then a high-ranking agent at the DEA in New York.

In 2007, his team — accustomed to apprehending members of Mexican and Colombian gangs flooding the city with cocaine — observed a dozen what he describes as “Chinese-looking” men at a stakeout of a dilapidated Brooklyn warehouse.

Donovan, who would go on to lead the capture — and recapture — of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the former Sinaloa boss, says it was the first time “many of us” had seen Chinese groups involved in the drugs business. “We didn’t know about it. It was an ‘aha’ moment,” he says.

Within a few years, says Donovan, who has since retired from the DEA, the Chinese became “the biggest money launderers in the world”.

Three developments in the 2010s supercharged their role. The first was the rise of encrypted messaging platforms, in particular China’s WeChat, launched in 2011.

Money brokers in the US identified customers “by posting advertisements on internet bulletin boards or private WeChat forums online”, US Treasury officials wrote in 2022.

Another development was the advent of untraceable cryptocurrency. Last year, the Manhattan district attorney disrupted a Chinese group that laundered more than $7mn using Bitcoin.

But by far the most consequential was the fentanyl epidemic. Between 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin or morphine, fentanyl is at least 20 times more profitable per kilogramme than cocaine, leaving its traffickers with much more cash that needs to be laundered.

“Fentanyl is what really made them grow by leaps and bounds,” Donovan says. By the eve of the pandemic, “Chinese groups were growing in power and prestige”.

While the huge profits being made from fentanyl have been widely publicised, the other side of the money laundering operation — the demand for dollars from Chinese individuals — is less well understood.

Capital flight from China is by no means a new phenomenon but in recent years the scale of these transfers has surged, according to both Chinese officials and analysts who track China’s international remittances.

“The levels of capital flight in the past three years have been quite alarming,” says one senior Chinese official, who declined to be identified and who says that a lot of billionaires and multimillionaires are trying to leave China and take their money with them.

“Some wealthy private entrepreneurs are losing confidence in China’s future. They feel unsafe so they are finding ways to get their money out.”

A regulatory crackdown on private enterprises that lasted for about two years from 2020, the ceaseless investigations into individual corruption and a sense that China’s military build-up could one day lead to conflict are prompting China’s wealthy to find exit routes for their capital.

In addition, some wealthy Chinese say that Xi appears ideologically opposed to personal wealth. His “common prosperity” policy, invoked in 2021, heralds what many believe will be a multi-year programme to redistribute wealth from the haves to the have-nots.

David Lesperance, a tax and immigration adviser based in Gibraltar, says the exodus of wealthy Chinese eclipses anything he has seen in more than 30 years.

“The last two years have seen the biggest exodus of my ultra-high net worth Chinese clients in over three decades,” says Lesperance.

Calculating the extent of capital flight from China is not straightforward. It requires forensic analysis of China’s balance of payments data to work out how much money is leaving the country through informal or illicit channels.

Brad Setser, a former US Treasury official and an expert on global capital flows at the Council on Foreign Relations, a US think-tank, estimates that as of the first quarter of this year, private capital flight from China was running at an annualised rate of about $516bn. It was even higher in the third quarter of 2022 when it hit nearly $738bn.

These levels are well above outflows in the last quarter of 2019 — before the pandemic struck early in 2020 — which were taking place at an annualised rate of $94bn.

Such levels of capital outflow are huge; they mean that a chunk of money roughly equivalent in size to Norway’s entire gross domestic product is set to depart for foreign shores this year.

“A lot of Chinese residents no longer believe that China’s economic trajectory is clearly positive, and thus no longer necessarily want to hold a large share of their wealth in China,” says Setser. “As a result, many are looking to find ways to move funds abroad, even though that is technically hard for many average Chinese residents.”

A myriad different ruses are deployed to spirit funds out of China. While experts and law enforcement officials believe the global networks of underground banks are the most common route, other methods involve over-invoicing for imports, using cryptocurrencies or charging payment for non-existent services overseas.

The rapid rise of Chinese money laundering groups has caught the attention of law enforcement around the world. In Italy, where the FT spoke to officials in Milan, Rome, Florence, Trento and Reggio Calabria, authorities are conducting a series of investigations they say reveal the close collaboration between Chinese money brokers and European organised crime.

Authorities believe Italian criminals have grown more reliant on Chinese underground bankers to not only launder the proceeds of their drug sales but also to pay for shipments of narcotics.

“The whole system of drug trafficking is being sustained by a network of clandestine [Chinese] money brokers,” says Giovanni Melillo, the chief prosecutor for Italy’s National Anti-Mafia and Terrorism Directorate, whose office has been coordinating the nationwide probes.

Giovanni Bombardieri, chief prosecutor in Reggio Calabria and a veteran in the fight against the powerful Calabrian mafia group known as the Ndrangheta, says recent investigations have shown how the mafia uses Chinese brokers to settle drug payments in Latin America.

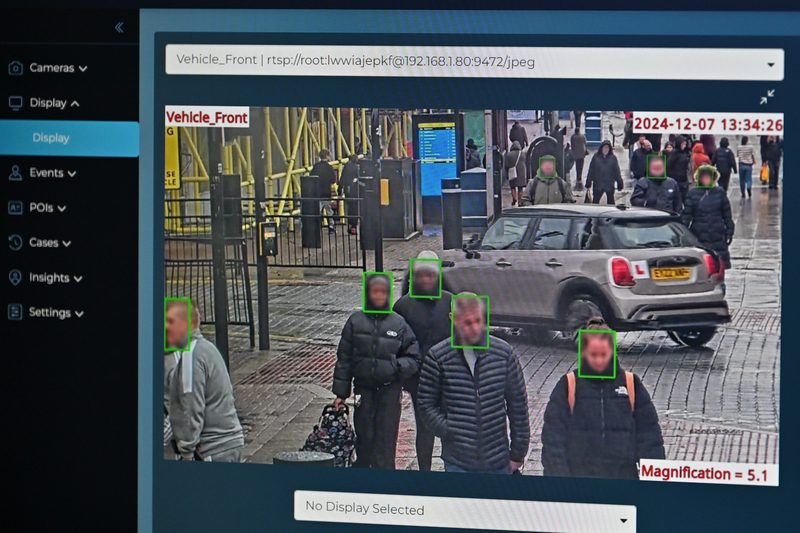

The proliferation of Chinese money brokers is also being investigated by the UK’s National Crime Agency. Sal Melki, head of illicit finance at the body’s National Economic Crime Centre, says Chinese underground bankers were increasingly “turning to criminals as a source of readily available cash” to help Chinese nationals abroad evade capital controls.

Previous cases of money laundering in the US involving Chinese nationals have raised questions about how much the Chinese authorities know about the transactions.

“The whole system of drug trafficking is being sustained by a network of clandestine [Chinese] money brokers.”

Giovanni Melillo, Italian prosecutor

In 2021, 48-year-old US resident Xizhi Li was sentenced to 15 years in prison after pleading guilty of leading a multimillion-dollar money laundering operation for traffickers of cocaine and other drugs. Another man, Xianbing Gan, was found guilty in Chicago of laundering half a billion dollars in drug proceeds and sentenced to 14 years.

Court documents filed by prosecutors in both cases showed that the brokers had laundered money through several of the largest and best-known banks in China.

“While China’s security forces normally tightly control and monitor its state-run economy, Li and others moved tens of millions of dollars among Chinese banks and companies with seeming impunity,” Celina Realuyo, a former senior state department official and professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs told a congressional committee last March.

Some officials who spoke to the FT said they believed the Chinese government, which is able to inspect messages on encrypted platforms that remain invisible to the western agencies, is not providing as much information to counterparts as it could.

But amid a recent easing in tensions between Beijing and Washington, Chinese authorities appear to have stepped up their international collaboration, arresting one of the key players in Martinez-Reyes’ organisation earlier this year. On a visit to Guangzhou in April, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen secured a commitment for more co-operation on anti-money laundering efforts.

“The Chinese have shown a little more interest in assisting with our investigations,” says one senior DEA official. “But it’s not something we have seen more than the last couple of months.”

© The Financial Times Limited 2024. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.