27 February, 2023 by Harry Dempsey, Leslie Hook and Robert Smith in London

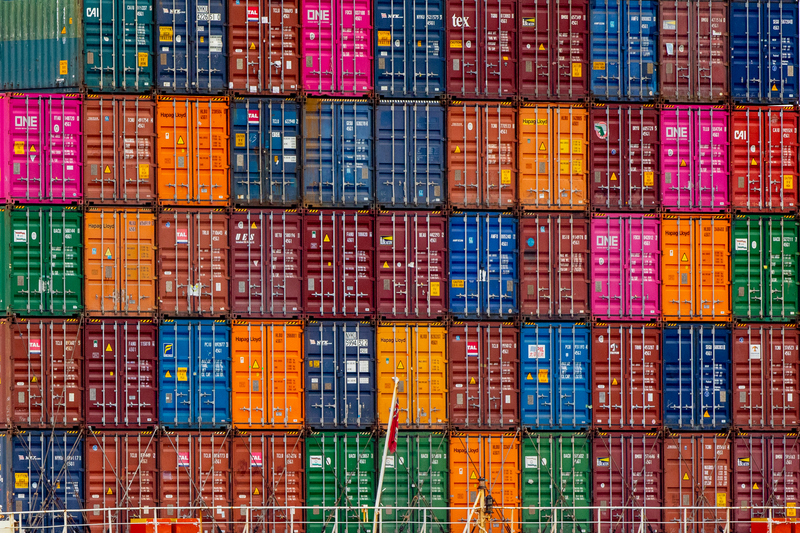

A heart attack, a handwritten note and 1,000 shipping containers full of unknown material — the details of one of London’s biggest commodity fraud cases read like a thriller.

Singapore-based trading house Trafigura has accused metals tycoon Prateek Gupta and his companies of selling it fake nickel cargoes worth hundreds of millions of dollars, in a high-profile lawsuit that has sent shockwaves through the sector.

Court documents show how the situation came to a head during a tense 10-day period in November as the relationship between the two sides soured, as well as how Trafigura faced mounting customer complaints including threats of legal action before it decided to pursue Gupta in the courts.

The filings, obtained by the Financial Times, provide fresh insights into how the alleged fraud against one of the world’s biggest commodity trading houses finally unravelled.

Trafigura alleges that 43-year-old Gupta was the “controlling mind” behind an array of linked companies including TMT Metals, UIL Malaysia and UIL Singapore, all of which are defendants in the case.

The trading relationship started in about 2014 with domestic zinc transactions in India and grew to global trades in nickel and aluminium.

By 2022, most of the deals between Trafigura and Gupta’s groups were “buyback transactions”. Trafigura would purchase a cargo from the group, own it during its journey — providing crucial trade financing — then sell it back to one of Gupta’s linked companies, or to a third party arranged by him or his colleagues, charging an interest payment.

However, in spring 2022 as nickel prices surged, Citibank — which was providing an $850mn line of credit to Trafigura to finance these transactions — started to become concerned about the size of the nickel deals and the length of time it was taking for the buybacks to occur.

By last summer Trafigura’s head nickel trader, Sokratis Oikonomou, had also become worried. “It came to my attention that the UIL entities had stopped entering any buyback transaction and stopped making any payments to Trafigura,” he wrote in court testimony.

At Citi’s request, Oikonomou arranged for a physical inspection of cargoes to take place on November 9.

But even before that could occur, Citi terminated its credit line, apparently alarmed by the “red flags” its due diligence had turned up, and Trafigura started to fund the cargoes from its own balance sheet.

As the date of the inspection in Rotterdam neared, Gupta said he was having medical trouble. Then on November 7, two days before the inspection, he said in a WhatsApp message to his counterpart at Trafigura that he had suffered a heart attack.

Citing his health, he resorted to bargaining. “I’m just closing terms for a large reduction,” he wrote, referring to a cut in the size of Trafigura’s nickel exposure with his companies. “However, I would need you to stall inspection,” he added, in order “to avoid any issues between us”.

Trafigura pushed ahead anyway. “My priority at the time was ensuring that the inspection . . . went ahead,” Oikonomou recalled in his written testimony.

When the containers in Rotterdam were opened, none was found to contain nickel. Inspectors instead found carbon steel, typically less than a 20th of the value of nickel.

While Gupta said he was still in hospital, managers at Trafigura learnt through news articles that he was also facing serious legal issues in India. The Indian Central Bureau of Investigation was probing Gupta and his company, Ushdev International, for allegedly causing a $174mn loss at the State Bank of India through illicit commodity trading, according to a charge sheet published in July (Gupta said in December that the charges had been settled, according to the court documents).

Upon his discharge from hospital in November, Gupta tried to strike a deal with Trafigura. He acknowledged the cargoes were not as expected and implied that he would buy them back as soon as he had the funds to do so.

As part of these discussions, Gupta presented Trafigura with a spreadsheet of 93 cargoes that were related to the dispute, and allegedly acknowledged that none of them contained high-purity nickel as specified by the contracts.

At various points, he and his business partner Arvind Prasad presented Trafigura with lists of assets that they proposed could serve as collateral while a phased repayment plan was put in place. These included a wind farm and a steel mill in India, a Singaporean energy company called Ultravolt, and an engineering group, Hangji Global.

Prasad did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Gupta also offered up letters of credit from Silver Bank, a small lender in Mauritius that has recently come under scrutiny for its ties to the metals trader.

During this period Gupta also tried to raise money by issuing bonds from TMT Metals Group. In a WhatsApp message to Oikonomou, he claimed to have one Swiss family office prepared to invest €100mn and another sovereign wealth fund from “a very respectable country” ready to invest $100mn.

Meanwhile, Trafigura was facing a new problem as customers to which it had sold some of the purported nickel shipments started to discover the cargoes contained the wrong material. Trafigura said in court documents that Gupta and his network had arranged the deals to the third-party clients.

While Gupta initially claimed TMT had raised €50mn through a bond sale, he later said know-your-customer “issues” were holding up the money from clearing. On Christmas Eve, Gupta hosted a video call between the bond investor — whose identity is not revealed in the affidavit — and Oikonomou to explain the “reasons for the delay”.

In a meeting near London’s Heathrow airport in early January, Gupta presented Oikonomou with a handwritten note outlining a repayment plan. He proposed paying $200mn by the end of March, with the remainder to come over the following two years. But Trafigura did not believe the proposal could be relied upon.

On November 17, Chinese client Xiamen C&D Aluminum Co alerted Trafigura to discrepancies in the customs codes and the certificates of analysis for the 286-tonne shipment it had received.

Two weeks later Xiamen threatened legal action. By early December, Trafigura had agreed to buy back the problematic cargoes it had sold to Xiamen’s subsidiaries.

Soon, another client, US-based Argentem, raised similar concerns. By early January a third, Singapore-based Mind ID, had opened supposed nickel containers and found none of the metal inside. A fourth customer, Hong Kong-based Axiom, arranged an inspection in Rotterdam on January 9, which revealed the same thing.

As the outcry from customers mounted, Trafigura’s management team met on January 10. Members of the trading, operations, insurance and legal teams all presented various options. Management decided that the time for bargaining was over — it was time to pursue a fraud claim and seek a worldwide freezing order of the defendants’ assets.

By the time that legal claim was filed in London courts four weeks later, even more evidence had piled up. Xiamen found more suspect shipments and wrote to Trafigura in early February saying that “the goods are completely wrong” and that “it is a fraud, not a simple quality problem”.

Xiamen, Argentem, Mind ID and Axiom did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A spokesperson for Gupta said his team was “preparing a robust response to the allegations from Trafigura and intend to share that soon”.

Meanwhile, Gupta was stalling for time, paying Trafigura $5mn in late January as he continued to try to raise more money.

While Trafigura’s court case has yet to run its course, it has taken a large financial hit. The commodities trader has announced a $577mn writedown and is negotiating with the customers that received the purported nickel shipments to find a solution.

The extent to which anyone at Trafigura was aware of what Gupta was up to remains unclear. The main trader on the Gupta account was Mumbai-based Harshdeep Bhatia, who also may have introduced the two parties, according to Oikonomou’s testimony.

Bhatia had an “apparent cosiness” with Gupta, according to a witness statement by Trafigura’s counsel Reza Ispahani that was based on their WhatsApp exchanges, although he said that there was “no direct evidence” that Bhatia was implicated in the fraud.

Ispahani’s witness statement added that “we have been unable to plug what we see as certain gaps in the WhatsApp exchanges” between Gupta and Bhatia. Bhatia did not respond to requests for comment.

There are also questions over Trafigura’s compliance procedures after the court documents revealed several missteps, including a failure to require analysis certificates and ignoring incorrect customs codes.

Trafigura has said it has “seen no evidence to suggest that anyone at Trafigura was involved or complicit in this illegal activity”, and that “the fraud is isolated to one specific line of business”.

Even the value of the material that is in the containers remains a mystery, according to the court documents.

More than 156 containers had been inspected by February 6, out of an estimated 1,100 containers involved. Some contained carbon steel, some other types of steel and iron products — but none so far has contained nickel or nickel alloy.

“The reality is Trafigura does not know what is in the containers,” said Oikonomou in his written testimony.

While any legal settlement could take months or even years, some cargoes are still at sea, with the latest due to arrive by May of this year.

As the court battle takes off, more clues are likely to be revealed.

© The Financial Times Limited 2023. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.