What matters

The article discusses the challenges and opportunities for the UK government to regulate AI in the private sector, and suggests some possible steps to achieve a competitive and ethical framework. It also reviews the recent parliamentary report on AI governance, and highlights some of the key issues the next government will have to address, such as data access, IP rights, environmental impact, and sector-specific regulation.

What matters next

Readers may consider engaging with the AI providers and regulators, and keeping abreast of the developments in the field, as AI regulation is likely to have a significant impact on various aspects of society and economy.

A recent UK parliamentary report, the last to be published before the upcoming general election, says that we need to “fundamentally change the way we think” about AI.

Should we? The report, from the House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Committee, contains persuasive analysis of the UK’s current “wait and see” strategy, and argues cogently for the UK to steer a third way between the stringent EU and more hands off US approaches to private sector AI governance. But it does leave some big questions which we believe the next government will have to get to grips with if the UK is going to come good on the promise of becoming a global AI leader.

Here’s our rundown of some key takeaways which we think the next government will need to address.

A USP for the UK

In the US, AI legislation is now gathering pace at state level – with the first comprehensive AI legislation passed in Colorado on May 17. We expect this to follow the same pattern as the development of data protection laws, where the US has ended up with a patchwork of different state laws with sometimes unpredictable results, such as the famed biometric rules in Illinois, while the federal law that many hope for remains elusive.

Here the UK stands to gain a competitive advantage by offering a unified approach, where both the EU and US will have to grapple with state divergence (again, just like privacy laws). But to fully capitalize on this, the UK will have to send some clearer signals of its intent on governance, and in that respect the report (which reflects a cross-party range of views) clearly signposts a preference for legislation in the next Parliament.

Three steps we believe would benefit any emerging legislative framework would be:

- forming a specialist regulator for AI;

- setting clear rules about the most high-risk categories of processing; and

- creating more definitive rules on the key issues of data protection and IP rights in the context of AI model training.

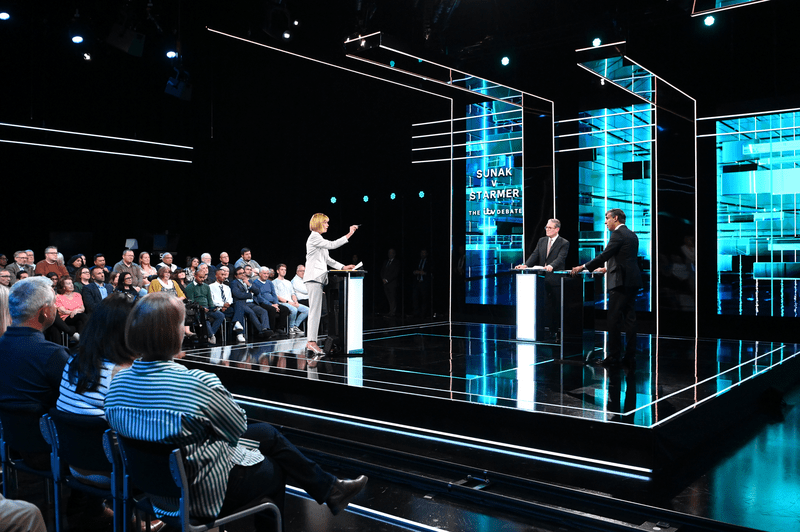

With the UK general election campaign now well underway, focus will inevitably switch to whether a change in administration may herald a different approach to UK regulation.

Not long before the Prime Minister fired the electoral starting gun, the Labour Party was poised to publish a much-anticipated AI strategy. Whether that strategy will materialise before July 4 remains to be seen, but the assumption from previous statements made by Shadow Department for Science, Innovation and Technology Secretary Peter Kyle is that a Labour government would be likely to be more inclined to seek a statutory solution, potentially picking up the baton of Lord Holmes’ Private Members Bill on AI regulation, which gained more traction than some expected in the latter months of the last Parliament.

Lessons from history

It has been argued that the UK runs the risk of giving away some brilliant tech at an early stage – for example through the recent safety evaluations platform launched by the AI Safety Institute. For some, this has uncomfortable echoes of the world wide web free-for-all in the 1990s. The incoming government will have a tricky task walking the line between showcasing UK AI capabilities by opening AI models to international scrutiny and maintaining the advantages of keeping them under wraps.

The report draws particular attention to the difficulty in getting the (predominantly big tech, cash-rich, US) developers to submit models as appeared to be promised at last autumn’s Bletchley Park AI Safety Summit. As the report notes, previous Parliamentary reports on AI have drawn out the potential strategic advantage to the UK’s AI businesses of striking a balance between open- and closed-source approaches, but there remains a risk of giving away the crown jewels.

Elephant in the room

The significant potential environmental cost of the infrastructure underpinning AI technology is raised in passing, citing concerns even within the AI industry around the water and electricity consumption inherent in supporting the growth of compute capacity needed to maintain AI platforms. It doesn’t, however, offer any cogent strategy to mitigate its effect, with environmental impact often lost behind the noise created by the much-vaunted AI “existential threat”.

Our engagement with leaders in the data centre and GPU manufacturing sectors suggests the appetite to address these points is there if the government is able to set out a clear and targeted framework on issues such as planning reform, green energy and environmental standards. We also know that work from the Bletchley summit was “inspired by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change”, so we hope this inspires some joined-up thinking.

The dangers of slicing too thinly

The report mentions the likely cost of keeping each regulator busy policing potentially complex AI issues in its sector, and this is certainly true. It calls for a big tech levy to fund AI regulation (similar to the recent call from banks for a levy to pay for online fraud). But the overriding concern with regulatory overlap risks missing the subtler but equal threat of “underlap”, where some AI deployment could fall between the cracks given many AI models are sector-agnostic.

An example of this has already emerged in the ICO’s discussion of legitimate interests in its draft guidance on data protection and web-scraping for generative AI, which doesn’t fully recognize that unlawfulness in one regulatory area (such as contract terms, or IP rights) can also fatally infect another (data protection: see Shoosmiths’ response to the ICO’s consultation on generative AI). This creates some potential gaps through which difficult problems may not be addressed in the ’light touch’ approach outlined to date.

The government has suggested that those gaps will be managed by the non-statutory ‘steering committee’ it intends to set up between government and the regulators, but the composition and remit of that committee is still to emerge. In that context, we’ll be intrigued to see whether an incoming administration may see the attraction of the overarching regulator that many (including some AI providers) think would be the better answer.

Leadership and the data challenge

Tech companies in the US have a huge head start on AI because of the resource riches accrued from advertising ecosystems. This leaves everyone else with a difficulty – not just financial, but also a lack of raw materials. As the report notes, the only data uniquely available to the UK is that created from national services such as the NHS and the BBC. Capitalising on this is a potential winner for the UK, but hugely difficult to pull off without undermining trust and transparency (and assuming that data can be effectively collated across the often-diverse government bodies currently holding it).

In the case of IP rights, the report calls for “a sustainable framework that acknowledges the inevitable trade-offs”. The treatment of IP by AI providers, subject to increasingly high-profile litigation, remains an issue for which no clear legislative solution has been presented (in the UK or elsewhere), and without a detailed and potentially far-reaching review of existing copyright and other laws, it is difficult to see how the IP challenge around AI models can be resolved.

On these and wider issues, we hope those picking up the baton of AI regulation after the general election – whoever forms the next government – are able to grasp the nettle and address the questions that remain unresolved.

Alice Wallbank is a profesional support lawyer in privacy & data. Alex Kirkhope is a partner in the Commercial team with a particular focus on technology and outsourcing, advising clients on all aspects of their business-critical IT systems and related business functions, as well as wider technology-based commercial contracts, software licensing and information law.