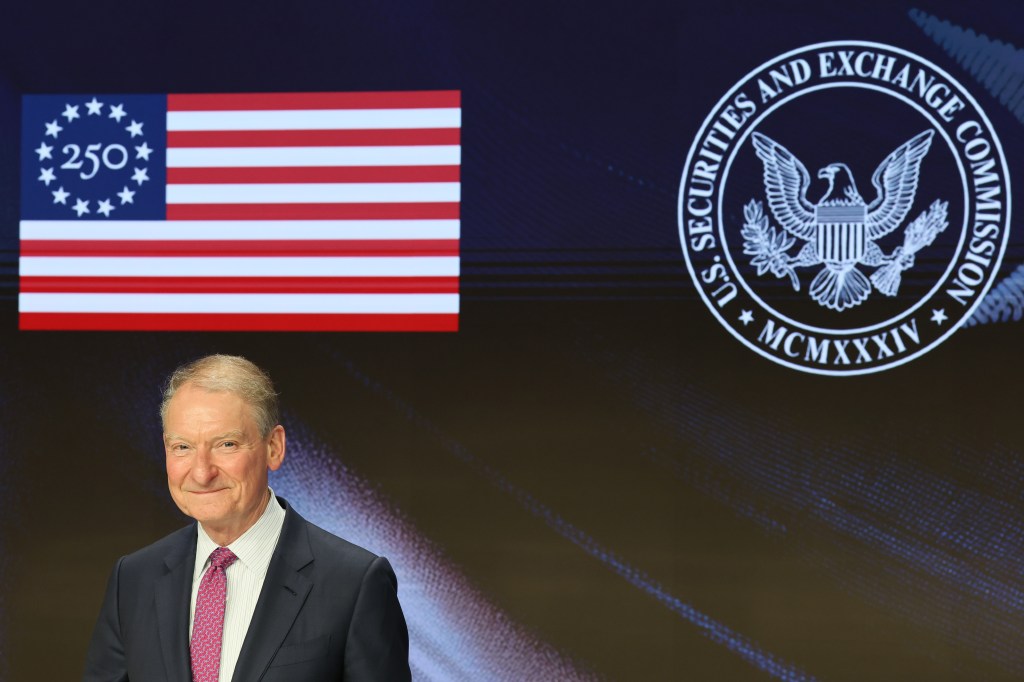

A US appeals court rejected an SEC rule intended to compel private funds — like hedge funds and private equity firms — to give investors more transparency via disclosures into these investments. The New Orleans-based Fifth Circuit Court decided the SEC exceeded its authority by adopting the rule in August

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day