Regulators

- Financial regulator: Finansinspektion – Financial Supervisory Authority

Finansinspektionen is the Swedish government agency responsible for the country’s financial regulation. It is responsible for the oversight, regulation and authorisation of financial markets and their participants. - Data protection authority: Integritetsskyddsmyndigheten (IMY) – The Swedish Authority for Privacy Protection

IMY’s role is to uphold the protection of personal data, monitoring that they are handled correctly and do not fall into the wrong hands.

Banking ecosystem

- Largest banks: Handelsbanken, Nordea, SEB, and Swedbank.

- Central bank: Sveriges Riksbank. It was founded in 1668 as Riksens Ständers Bank (the Estates of the Realm Bank) by the Riksdag, Sweden’s parliament, and changed name in 1867 to Sveriges Riksbank. The Riksbank is the oldest central bank in the world.

- Currency: Swedish krona (SKr)

Expert snapshot

8 questions in collaboration with Noah Taha, Associate at CMS Wistrand in Stockholm, Sweden.

1. Who are the main regulators for financial services in Sweden and how would you describe their appetite for regulating the markets?

The primary regulator of financial services in Sweden is the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority. Usually, they approach the regulation of financial services with a proactive attitude and a strong focus on systemic risks. Their regulatory attitude could be characterized as consumer-friendly and in alignment with international standards, primarily those set by the European Union. Additionally, the authority is committed to keeping up with the technological advancements happening in the financial sector.

2. What are the main sources of regulatory laws in your jurisdiction?

In Sweden, the regulatory framework governing the financial services and markets comprises a mix of legislative laws and regulations issued by different authorities. Key sources of laws and regulations include the Banking and Financing Act, Insurance Business Act, Anti-Money Laundering Act, Securities Markets Act, as well as regulations and guidelines issued by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority. In addition to the domestic legal framework, the regulatory structure is complemented by the European Union directives and regulations, which further influence and define the applicable legal framework.

3. How can firms outside of Sweden do financial services business in your country?

Firms outside of Sweden looking to conduct financial services business within the country have two clear and convenient options:

i) they can establish a Swedish subsidiary operating under Swedish laws and regulation which is partly, or wholly owned by them as a foreign entity, or

ii) start a branch company as an extension of a foreign company, operating under Swedish laws and the laws of the country where the parent company is based.

4. What types of activities require a license in your jurisdiction?

In Sweden, several types of financial activities require a license to operate. Those include:

- banks;

- payment service companies;

- companies operating within stock exchanges and clearing;

- fund management companies;

- funds;

- insurance companies;

- insurance intermediaries;

- mortgage institutions;

- consumer credit institutions;

- credit market companies;

- issuers of electronic money; and

- securities companies.

Each of those activities must obtain the appropriate licenses from the relevant regulatory authorities.

5. What are your top 3 enforcement actions and briefly explain in a sentence or two why the firms were censured.

- Swedbank received a warning and had to pay an administrative fine of SKr 4 billion.

Infraction: Swedbank had demonstrated major deficiencies in its work to combat money laundering in its Baltic operations. The bank’s Swedish operations had not complied with the requirements of the anti-money laundering regulations. - Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB) received a censure and had to pay an administrative fine of SKr 1 billion for deficiencies in its work to prevent money laundering risks.

Infraction: SEB’s subsidiary banks in the Baltics had been exposed to an elevated risk of money laundering. This is due in part to their geographic location but also because customers with a higher risk of money laundering have represented a substantial portion of the subsidiary banks’ business volumes and transactions. - Swedbank received a censure and had to pay an administrative fine of SKr 850 million.

Infraction: Swedbank made a change to a business-critical IT system without following its own internal procedures and processes. It did not have suitable control mechanisms in place to be able to capture the deviation and ensure that internal procedures and processes were followed. As a result Swedbank did not have satisfactory internal control of the change to its IT system. The resulting outage impacted almost a million of the bank’s customers.

6. What is the regulatory attitude to crypto?

In Sweden, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority is the primary body overseeing the crypto market. Their attitude can be described as “cautious” and they are gradually trying to incorporate crypto into the current financial system controls (AML, KYC).

7. Where does business stand on ESG?

Swedish businesses are highly engaged and proactive in addressing ESG matters, aligning with both Swedish and European legislative frameworks. Many companies voluntarily adhere to international standards on ESG, reflecting their importance for external investors, market and stakeholders. Generally, ESG considerations are prioritized and integrated into many business strategies.

8. What is your government’s position on data privacy? What are the biggest concerns?

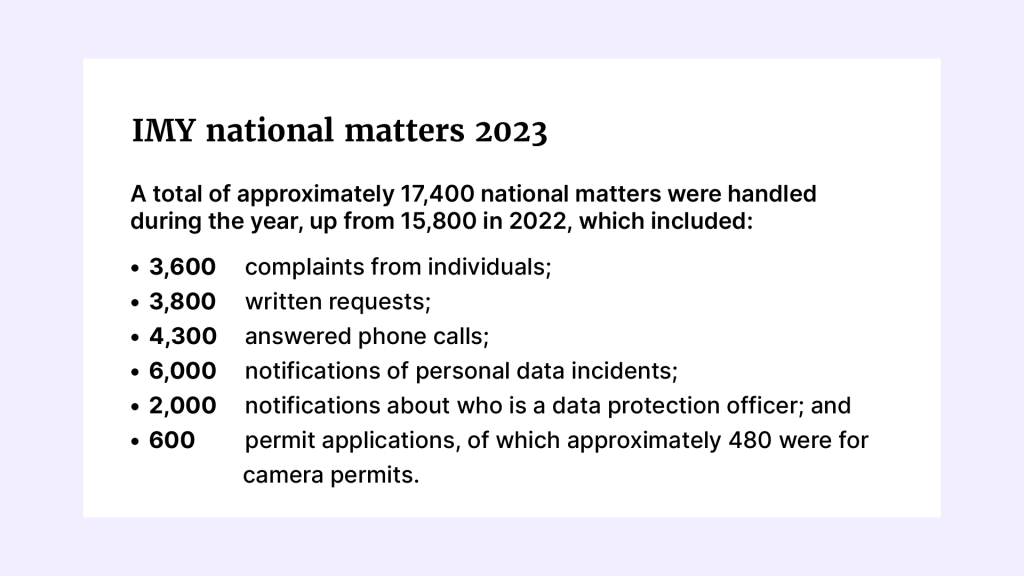

Sweden and its legislators maintain a highly stringent view of data privacy, resulting in close alignment with GDPR requirements. The supervisory body is The Swedish Authority for Privacy Protection. Additionally, two areas are usually areas for concern and scrutiny: i) data security to protect personal data against breaches and unauthorized access, and ii) data transfers to jurisdictions outside of EU and its compliance with GDPR.

Compliance

Money laundering

On August 28, 2024, Finansinspektionen notified the European Banking Authority (EBA) that it intends to follow the EBA’s updated guidelines (EBA/GL/2024/01) on risk factors regarding money laundering and terrorist financing. That includes updated guidelines on money laundering and terrorist financing risk factors regarding crypto assets and crypto service providers.

Sweden has earlier faced criticism for its work against money laundering. In September 2023, a report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that Nordic and Baltic banks should take efforts to strengthen their anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CFT) supervision framework further.

In May 2024, Riksrevisionen, the Swedish National Audit Office, found that the work of the Swedish state and some authorities to prevent money laundering lacked effectiveness. Riksrevisionen said that the government’s management of the system for money-laundering supervision is weak, and that supervision by Finansinspektionen (the Financial Supervisory Authority) and the county administrations in Stockholm, Malmö, and Västra Götaland is not effective enough.

In August 2024, a new report was released highlighting a higher risk of money laundering through neobanks. One key reason identified in the report is that neobanks – completely digital banks – only use digital and rapid customer recognition and verification processes, which often means a “lower degree of control.” This in turn is an enabler for another layer of anonymity, including the risk of account holders becoming ‘account keepers’ or ‘money mules’ on behalf of criminal organizations.

Nordic and baltic banks have repeatedly fallen afoul of money laundering regulations.

- 2019: the Swedish TV news show Uppdrag Granskning revealed extensive suspected money laundering within Swedbank, where at least SKr 40 billion ($3.9 billion) had been channelled between accounts in Swedbank and Danske Bank in the Baltics. The suspected crimes were linked to a former minister in the Russian government, Mikhail Abyzov.

- 2020: Swedbank was fined record $400m fine due to ”major deficiencies in its work to combat money laundering in its Baltic operations.”

- March 2022: Swedbank was served with another suspicion of money laundering notice at its Estonian branch for events in the period 2014-2016. Later in October, Swedbank’s former CEO Birgitte Bonnesen went on trial for allegedly covering up massive money laundering in the bank’s Baltic branches – she was subsequently cleared of all these allegations.

- June 2023: Swedbank AS in Latvia, a subsidiary of Sweden’s oldest bank Swedbank AB, paid $3,430,900 to the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to settle its potential Crimea sanctions. Allegedly, throughout 2015 and 2016, OFAC found 386 violations of its Crimea sanctions, where a Swedbank Latvia customer used the e-banking services from an IP address in Crimea to make transactions to persons in Crimea through US correspondent banks totalling up to $3,312,120.

- September 2024: Birgitte Bonnesen, the former CEO of Swedbank, was sentenced to prison for one year and three months after being convicted of gross fraud. The Court of Appeal found that Bonnesen did provide misleading information when she was interviewed by Swedish media (Svenska Dagbladet and TT) regarding the release of its third quarterly report in 2018. According to the Court, Bonnesen provided misleading information that the bank had no suspicion of money laundering events going on in the Baltics. That information was “likely to influence the assessment of the Swedish bank in financial terms and thereby cause damage.”

Data

Data protection

In June 2024, the Nordic data protection authorities in Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Åland came to a new agreement to join forces on children’s data protection in gaming, Al, and administrative fines.

Technology

Cybersecurity

With Sweden joining NATO in March 2024, a number of its authorities and organizations have been attacked in cyber and ransomware attacks by pro-Russian cyber groups. These included Finansinspektionen, the private clinic Sofiahemmet in Stockholm, and multiple municipalities.

In early 2024 an investigation uncovered that Chinese hackers had been using Swedish routers to send malicious emails, affecting thousands of victims across the world. Politicians in Sweden, American senators, British members of parliament and European members of the Inter-parliamentary alliance on China (IPAC) are among millions of people to have been impacted.

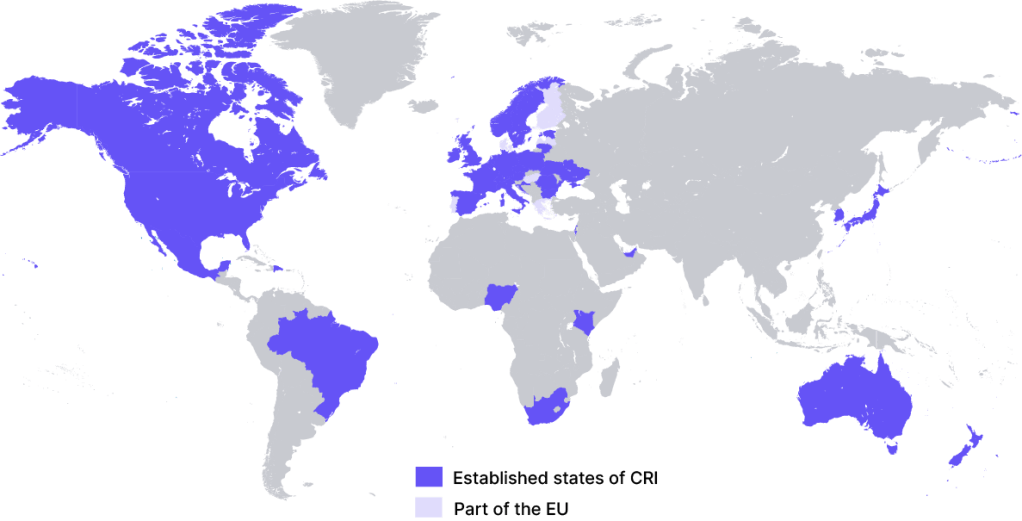

In November 2022, representatives from 36 countries and the EU met to continue their work to fight ransomware, and issued a joint statement after their second International Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI) Summit, convened by the White House.

Since the first meeting in autumn 2021, the CRI members have been working on five core goals:

- increase resilience;

- disrupt ransomware cartels;

- counter money laundering;

- build partnerships with private sector cyber firms; and

- strengthen international cooperation.

Sweden is a CRI member.

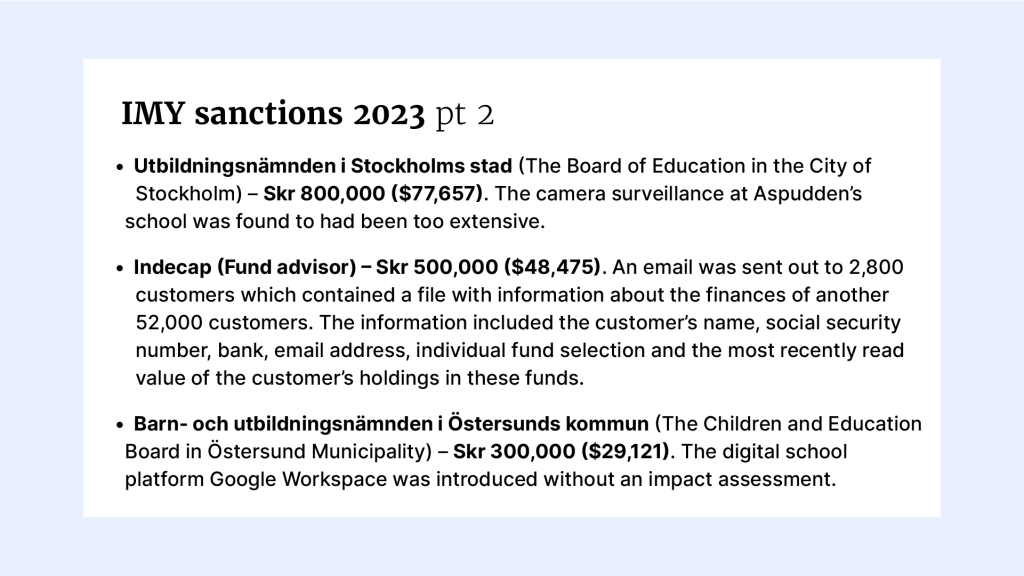

Notable regulatory actions and fines

- June 2024: Nasdaq Stockholm fined SKr 100m ($9.6m) for regulatory violations connected with insider dealing and unauthorized trading. It had failed to report suspected insider dealing to the authority as required by Article 16(1) of the EU Market Abuse Regulation (EU MAR) and section 7 of the Swedish Securities Market Act on four occasions in 2021 and 2022.

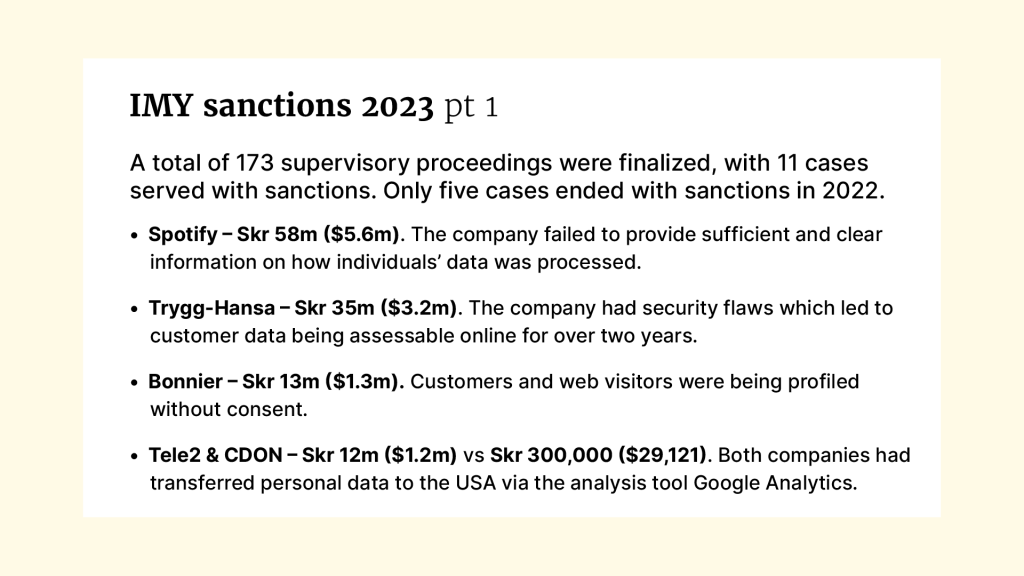

- March 2024: The Swedish payments group Klarna was fined Skr 7.5m ($733,324) for violating the EU’s GDPR by failing to provide adequate information to its users.

- September 2023: Insurer Trygg-Hansa sanctioned Skr 35m ($3.2m) over having data of 650,000 customers online for more than two years. Without having to log in, anyone could access customers’ data to one of their branches, Moderna Försäkringar, by just switching some of the numbers in the website’s URL

- June 2023: Spotify sanctioned Skr 58m ($5.6m) for failing to provide sufficient and clear information on how individuals’ data was processed.

- March 2023: Ericsson plead guilty and paid $206m after breaching a 2019 deferred prosecution agreement. The company was guilty of engaging in a long-running scheme of violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act by paying bribes, manipulating books and records, and failing to implement proper internal accounting controls in several countries.

- 2020: Swedbank fined a record $400m due to ”major deficiencies in its work to combat money laundering in its Baltic operations”.

The materials on the GRIP website are for general information purposes only and do not constitute legal advice. While reasonable care is taken to ensure accuracy, the materials may not reflect the most current legal developments. Always consult a qualified lawyer for specific legal matters.