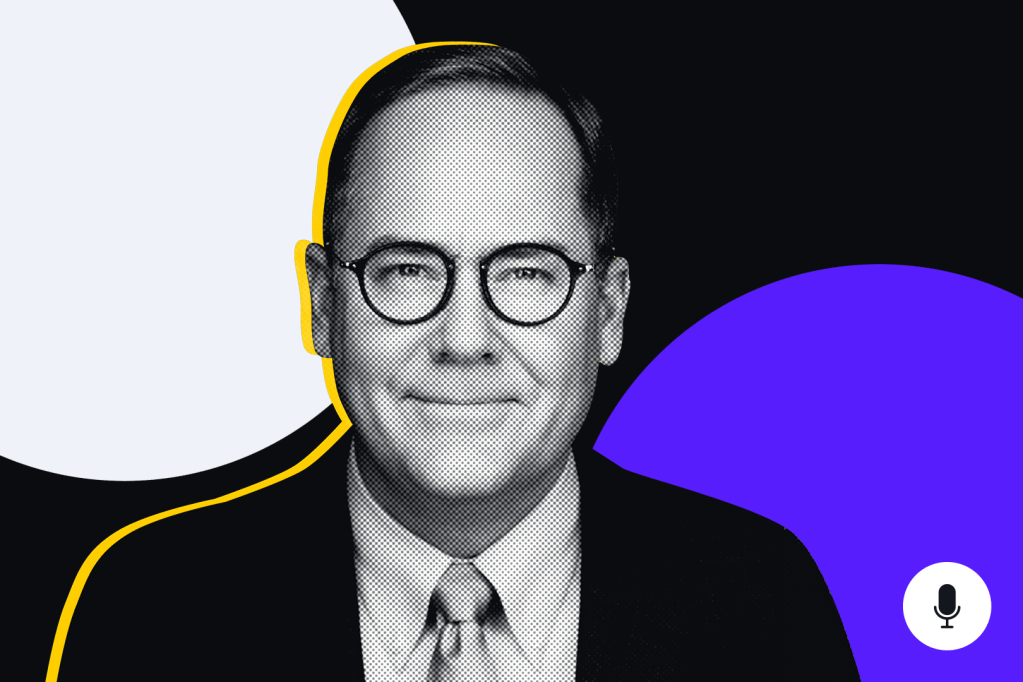

The role of supervisors as guardians of trust in banking was highlighted by Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael Hsu in a keynote speech at a European banking conference in Frankfurt, Germany recently.

As the banking system evolves, Hsu said, then so should the role of supervisors. Given last spring’s

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day