The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is responding to a significant increase in the volume of event contracts listed for trading on its registered exchanges.

In his public statements and remarks on the proposed rule change, Chairman Rostin Behnam points out that “more contracts were listed for trading in 2021 than had been listed in the prior 15 years combined. And that has continued to be true each year since.”

The regulator has also observed applications for exchange registration “from entities that have indicated that they are interested primarily, or exclusively, in listing event contracts for trading,” including those specifically betting on the outcome of the US elections.

Responding to what Chairman Behnam calls an “exponential increase,” the CFTC is putting forward a change to its regulations that will further stipulate the types of event contracts that fall within scope of the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) prohibition as being contrary to the public interest.

By aligning the language of its rule more closely with that of the CEA, the CFTC is attempting to distinguish more clearly between contracts that are permitted and those that are prohibited under the Act and its own rules.

Scope of the rule

Examples of contracts that fall outside of the scope of the rule and are permitted are those that are based on a change in the price, rate, value, or level of the following indicators:

- Economic indicators:

- US trade deficit;

- GDP;

- jobless claims;

- unemployment rate; and

- US new home sales.

- Financial indicators:

- Federal funds rate;

- US credit card debt;

- fixed-rate mortgage averages; and

- end-of-day, week or month values for broad-based stock indices.

- Foreign exchange rates or currencies.

Examples of contracts that are prohibited include those that are agreements, transactions or swaps that involve:

- activity unlawful under Federal or State law;

- terrorism;

- assassination;

- war; and

- gaming.

According to the CFTC, most of these enumerated activities do not require further definition, but the regulator is putting forward a new definition of “gaming” as – the staking or risking by any person of something of value upon:

- the outcome of a contest of others;

- the outcome of a game involving skill or chance;

- the performance of one or more competitors in one or more contests or games; or

- any other occurrence or non-occurrence in connection with one or more contests or games.

The CFTC, in its proposal, points out that “gambling is overseen by state regulators with particular expertise” and the CFTC “is not a gaming regulator.” The new definition is intended to ensure that instruments that are in effect “bets or wagers on contests or games” are not permitted to trade on CFTC-regulated markets.

Public interest considerations permeate this entire proposed rule change, with Chairman Behnam making particularly pointed comments on the CFTC’s motivation in making these changes.

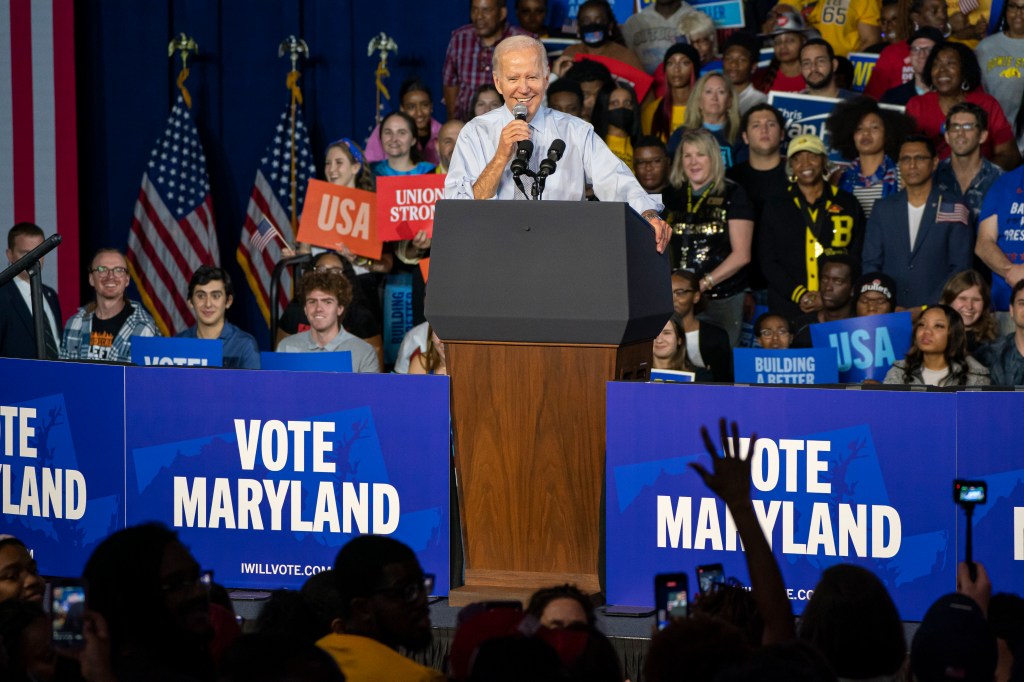

“Contracts involving political events ultimately commoditize and degrade the integrity of the uniquely American experience of participating in the democratic electoral process,” he said. “Allowing these contracts would push the CFTC, a financial market regulator, into a position far beyond its Congressional mandate and expertise. To be blunt, such contracts would put the CFTC in the role of an election cop.”

Dissenting views

Commissioners Summer K Mersinger and Caroline D Pham have both issued dissenting statements, disagreeing with aspects of the proposed rulemaking.

Commissioner Mersinger supports efforts to establish a framework around the exercise of the CFTC’s discretionary authority in connection with event contracts. But in a lengthy dissent, among other objections, she paints this proposal as one exceeding the legal authority granted to the CFTC, laying the foundation for the prohibition of entire categories of future event contracts and flying in the face of the CFTC’s mandate to promote responsible innovation.

She suggests that while she is not a fan of all event contracts, this rulemaking is a very clear example of regulatory overreach.

Commissioner Pham’s criticism is even more pointed: “The Event Contracts Proposal bigfoots into State regulation of gaming by drawing unintelligible lines in the sand that will either at best result in confusion for State gaming authorities, or at worst push event contracts into illegal, unregulated offshore markets.”

An interesting aspect of Commissioner Pham’s dissent is her observation that the rulemaking proposal “completely omits any discussion of the comment letters the Commission recently received.” According to the Commissioner, 200 comments were received by the CFTC and that “[i]t strains credulity that the Commission has selective amnesia and makes no mention of these letters” in its rulemaking proposal.

Given this, as well as the Commissioner’s scepticism about what she considers the CFTC’s “misplaced election integrity concerns” it will no doubt be interesting to observe the progress of this proposed rule change.

Social media, deepfake and US election

The CFTC’s rule proposal arrives squarely in a major US presidential election year and when disinformation – disseminated by some lesser-scrutinized social media channels – and the use of deepfake images are on the minds of election officials.

Additionally, the agency has been sued by online prediction markets that offer exchanges on political and financial events, including PredictIt, which the CFTC has tried to shut down, and New York-based exchange KalshiEx, whose application to list event contracts was rejected.

In its lawsuit, Kalshi claims the CFTC can evaluate whether a bet on an event is in the public’s interest only if the event itself is related to “crime, a terrorist attack, an assassination, an act of war, or gaming.”

But industry groups that support the rulemaking point out that the CFTC does not have the budget or expertise to be regulating and policing elections, which should be done by others like the Federal Election Commission and, as noted above, the states. The agency should not serve as a platform for excessive speculative gambling on political outcomes, they argue.