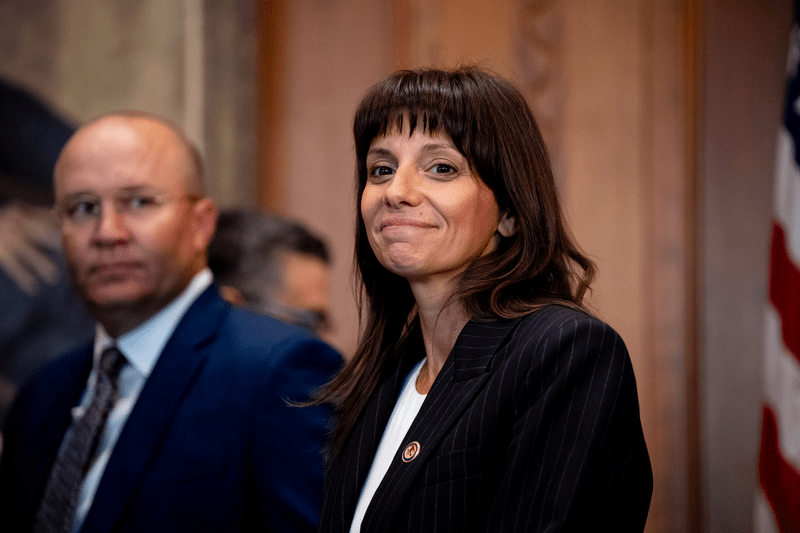

Encouraging individuals to speak out, and incentivizing corporations to improve compliance were the objectives emphasized by Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Nicole Argentieri at a recent NYU Law event.

In an appearance at NYU School of Law’s Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement, Argentieri talked about the Department of Justice’s

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day