Three years ago, I had not heard of SLAPPs, but they have since become a prominent feature of our public life. A SLAPP is a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. What it boils down to is the deliberate use of the law by the very wealthy to financially intimidate and deter anyone – usually journalists, writers and their publishers – from investigating their activities and publishing the results.

As such, they are extremely harmful. Only available to the super-rich, they are almost exclusively used against people who are trying to shine a public interest light on financial crime, corruption and other kinds of serious misconduct. The Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe, CASE, defines SLAPPS as “an abusive lawsuit filed by a private party with the purpose of silencing critical speech.”

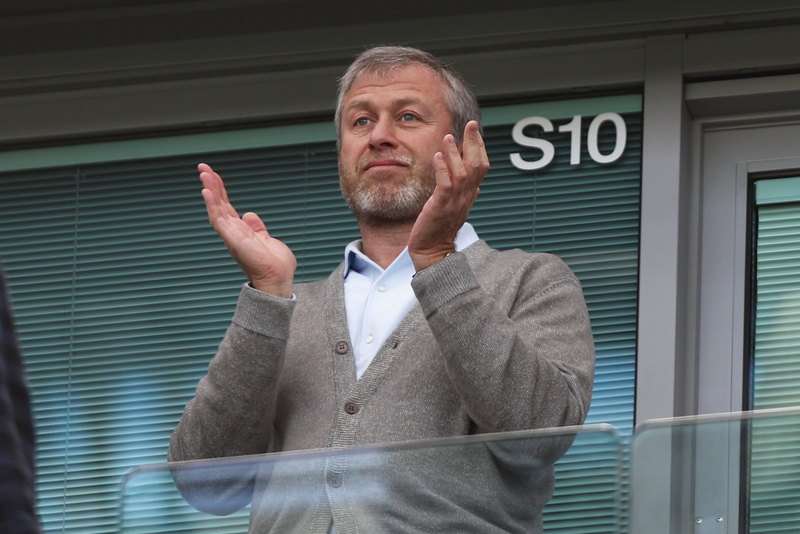

To understand the reach of SLAPPs and the threat they pose, it’s worth reading the UK Government Factsheet and the linked paper from the Foreign Policy Centre (FPC), which gives a list of relevant recent cases. These include: Arron Banks v Carole Cadwalladr; ENRC v Tom Burgis and HarperCollins/Financial Times; and Roman Abramovich v Catherine Belton and HarperCollins. To this list can be added Yevgeny Prigozhin v Eliot Higgins.

And, critically, only a subset of SLAPPs, probably a small minority, ever reach the public arena. There will be many more that successfully intimidate their targets and so prevent publication.

Economic crime

In response, a broad campaign group, the Anti-SLAPP coalition, together with a cross-party coalition of MPs, has persuaded the Government to introduce an anti-SLAPP amendment to its Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill. While limited in scope, this represents clear progress. And while its main focus is the legal sector, the amendment’s focus on economic crime means there are implications for other regulators, notably in financial services, and for those with the wider responsibility for oversight of the City of London.

We need to recognise, however, that the present regulation of the legal sector – its structure, powers, resources and culture – is not adequate to implement the anti-SLAPP amendment effectively. This is not a criticism; the current system was just not set up with SLAPPs in mind. Consequently, as things stand, those who perpetrate SLAPPs and the law firms that “enable” them are likely simply to price in the risk of fines and other sanctions as a cost of business and carry on as before.

Therefore, in the absence of a fundamental overhaul of the framework for regulating legal services, unlikely in the short term, the only realistic prospect of anti-SLAPP legislation succeeding would require a new level of collaboration between regulators. As well as the existing regulators of legal services, this would involve the Bank of England/PRA, FCA, City of London Corporation and possibly others.

Four pillars of collaboration

Such a collaboration would likely be based on a shared acceptance of the following four statements:

- Regulators have a collective responsibility to work together to combat financial/economic crime.

- SLAPPs should become a focus of attention because they are, to quote the Bill factsheet, “a misuse of the legal system“, and their profile and growing scale tarnishes the City of London’s reputation.

- The nature of SLAPPs means that the legal services’ regulators, as presently constituted, are unlikely to be able to establish an effective deterrent by themselves, so they will need help.

- Providing this help is justified because the nature of SLAPPs raises wider questions not only for the law firms that enable SLAPPs but for other regulated firms that do business with them.

Acceptance of these statements should lead regulators to explore together how they can best use their powers to remove the stain of SLAPPs from our public life.

Background: the growth of SLAPPs

Prominent MPs, such as David Davis and Bob Seely have used Parliamentary privilege to name legal firms and individual lawyers who offer SLAPPs or act in such cases. Bob Seely introduced an Anti-SLAPP Bill last January (see 14:55 onwards), during which he names law firms involved in some of the most notorious cases. The Bill followed a call, in November 2022, from a broadly-based UK Anti-SLAPP coalition, for the Government to back meaningful protections against SLAPPs.

As well as an attack on freedom of speech, the growth in SLAPPs is also a key aspect of a major national security issue. In 2020, Parliament’s Intelligence & Security Committee (ISC) published its Russia Report, which concluded that “Russian influence in the UK is the new normal (which) has led to a growth industry of ‘enablers’ including lawyers, accountants, and estate agents who are – wittingly or unwittingly – de facto agents of the Russian state”.

Since then, with Russia’s war against Ukraine and the consequent sanctions on various Russian oligarchs and companies, this story has moved on, but the core issue remains largely the same. In late 2021, for example, the late Yevgeny Prigozhin, then Head of the Wagner Group, was able to file a SLAPP lawsuit against Eliot Higgins, founder of Bellingcat, the open source news agency. The story of the suit is an essential read, as is a BBC article about how Prigozhin, despite being sanctioned, was able to bring the case.

Although the case was ultimately dropped, Higgins was left with £70,000 ($86,000) of legal costs and his lawyers have made a formal complaint to the Solicitors’ Regulation Authority (SRA) against London-based Discreet Law, the firm that initially acted for Prigozhin.

UK, EU and US

On the legislative front, the UK Government has introduced an amendment to its Economic Crime Bill, now in its final stages, and has also promised to use secondary legislation to cap defendants’ costs. This is an important first step, but limited in that, for example, it covers only economic crime and contains no means of either compensating the defendant or punishing the claimant. Partly as a result, there is growing pressure for a standalone anti-SLAPP law to be included in November’s King’s Speech.

There is also legislative progress internationally, including in the EU, where a draft recommendation for member states, potentially a pivotal document, is due in December. And in the US, where some 30 states already have anti-SLAPP laws, there are some moves towards a federal law, while the US Government’s Strategy on Countering Corruption (2021) recognises how SLAPPs have links into this.

However, the picture is more complicated when we turn to regulation.

The SRA, which regulates solicitors in England and Wales, has a SLAPPs webpage that includes a warning notice, a helpful-looking guidance page for those targeted by SLAPPs, and an invitation to report abusive litigation. However, its response has limitations, including that none of the case studies in its guidance on Conduct in Disputes covers SLAPP issues (presumably because there has not yet been a completed case).

The SRA has also conducted a Thematic Review – the findings were published in February this year – but found no evidence of SLAPPs, and its main findings were around knowledge and training. It is difficult to properly assess this outcome without knowing more detail, but it seems reasonable to infer that the SRA’s open cases, of which there were around 40 at the time and which presumably include those covered by MPs in Parliament and by the FPC paper, were excluded from the review.

“The UK Government has announced plans for reforms that would tackle SLAPPs by enabling cases that lack merit to be struck out early, avoiding excessive costs for those on the receiving end.”

MArk Neale, Director General, Bar Standards Board

Looking ahead, however, if the SRA at some point concludes that at least some of these cases are SLAPPs and takes enforcement action accordingly, then appeals seem inevitable.

Meanwhile, the Bar Standards Board (BSB), which regulates barristers, is also supportive of the amendment, most notably in this April 2023 blog by its Director General Mark Neale: “The UK Government has announced plans for reforms that would tackle SLAPPs by enabling cases that lack merit to be struck out early, avoiding excessive costs for those on the receiving end. Such processes will be welcome and will enable the identification of cases where there is a legitimate cause of action or where the case is an abuse of process.”

Many regulators would have gone further, setting an expectation for the regulated community to identify such cases themselves and not become involved. However, there does not yet appear to be a warning notice or specific guidance, and the rest of the blog is a carefully argued defence of barristers’ current practices, in terms of both the “cab rank” principle and the requirement not to discriminate when deciding which cases to take.

Elsewhere, the Legal Services Board (LSB), the oversight regulator for the sector, makes a brief reference to SLAPPs in its Annual Report 2022/23 (p21), as a thread of its work on professional ethics, but they do not get a specific mention in the Business Plan 2023/24. And the Bar Council and the Law Society, the sector’s respective membership organisations, have both welcomed the Government amendment, though with the caveats you would expect.

Is the UK regulatory system fit to combat SLAPPs?

In his introduction of the Anti-SLAPP Bill, Bob Seely MP identified four sectors that were involved – solicitors, barristers, private investigators and (in a separate regulatory category) data subject access requests (SARs). So, we need to look at the operational arrangements and powers of the relevant regulators in each sector. Apologies for any inadvertent over-simplification in what follows; hopefully the source links are helpful for those who wish to look deeper.

Legal services

The regulatory framework is relatively complicated, as the linked diagram on the Legal Services Board (LSB) website demonstrates. For the purpose of this article, I have focused primarily on the “Independent Regulatory bodies” for solicitors and barristers. Of the resulting omissions, the most notable are the Law Society and Bar Council, both of which have their own important roles to play.

Legal Services Board

The LSB is the oversight regulator for the sector in England and Wales and has responsibilities across nine approved regulators who, between them, regulate over 190,000 lawyers. According to its Annual Report, it has 27 full-time and 12 part-time employees, and a budget of £4.3mn ($5.4mn).

Solicitors Regulation Authority

The SRA’s Business Plan & Budget 2023/24 “welcomed the increase in our powers to fine traditional firms and those who work in them up to £25,000 ($31,000), and sharpened further our focus … on Strategic Litigation against Public Participation – SLAPPs”. As I read it, if the SRA wants to levy a higher fine, this needs to be passed on to the Solicitors’ Disciplinary Tribunal (SDT) for decision. And while the £25k ($31k) maximum limit now seems likely to increase, it is hard to see it reaching a level that would act as an effective deterrent to SLAPPs, which are typically financed by the super-rich.

Looking again at the warning notice, there may also be some work needed to establish meaningful precedents for taking enforcement action against firms that enable SLAPPs. As the notice puts it, the “guidance also highlights that it is improper to bring cases or allegations without merit, or to do so in an oppressive, threatening or abusive manner”. However, other regulators’ experience suggests it may be hard in practice to establish that a firm’s conduct breaches these thresholds.

Turning to the SRA’s overall resources, its budget for 2023/24 (p6) is just under £100m ($123m), of which around 25% is spent on Investigation & Supervision, 7% on Legal & Enforcement, and 4% on Anti Money Laundering. The total allocation for “external disciplinary and enforcement legal costs” is £4.6m ($5.6m) (p25).

So, much like its fining powers, the SRA’s resources, given its other responsibilities, are not obviously designed to hold prominent firms and lawyers to account over an area like SLAPPs where the financial rewards are high. Unless this changes, the result, almost certainly, will either be a lack of action on SLAPPs, a significant reduction in the SRA’s other activities, or, most likely, a miserable half way house that pleases no one and damages the SRA’s reputation.

Bar Standards Board

The BSB’s Business Plan & Budget 2023/24 shows the regulator’s budget as £14.7m ($18m) (p19), of which £3.6m ($4.4m) is assigned to Regulatory Operations and £2m ($2.5m) to Legal & Enforcement. Again, it is hard to see that the BSB is resourced to combat SLAPPs, and the implication of the Director General’s blog is that identifying a SLAPP is essentially a matter for the courts. Although he does then add that: “Such processes will be welcome and will enable the identification of cases where there is a legitimate cause of action or where the case is an abuse of process.” This at least leaves the door open for some form of enforcement against barristers whose cases are identified as SLAPPs by the court.

At present, it is hard to know what sort of enforcement action the BSB might take on SLAPPs, though this will presumably become clearer once the Economic Crime Bill becomes law. Like the SRA, many of the BSB’s disciplinary decisions are taken by a separate body, in this case the BSB’s Independent Decision-making Body (IDB). However, as for the SDT, deciding on disciplinary cases involving SLAPPs looks to be well beyond the IDB’s normal business.

Also, despite being “Independent Regulatory bodies”, both the BSB and the SRA are connected to the respective membership organizations, the Bar Council and Law Society (for example 5/11 BSB Board members are barristers). This strong element of self-regulation makes action in areas like SLAPPs, which might force some members to alter their business models significantly, all the harder. And interestingly, although he does not mention SLAPPs, the BSB Director General recently gave a speech calling for independent regulation of the Bar. But, even if it happens, that is for the future.

Private Investigators

This sector is not regulated in the UK, although the Government has flirted with bringing PIs under the regulation of the Security Industry Authority (SIA). The best description of the current position I have found is a blog from the Association of British Insurers, on the Law Society website, which instead advocates a voluntary framework.

Information Commissioners’ Office

The ICO is the body responsible for regulating SARs (Subject Access Requests), which are sometimes used in SLAPP cases to significantly increase defendants’ costs by asking for large amounts of detailed information that is peripheral to the case. Unhelpfully in this context, the ICO’s sole purpose is to “uphold (the) information rights”, so it is not well placed to protect defendants in SLAPP cases from the exploitation of information requests.

The ICO does, however, acknowledge the Government’s proposals in its draft Data Protection and Journalism Code of Conduct. For instance, the impact assessment notes that the code “aligns with (their) general spirit” and “explains that there is a way to refuse requests to exercise data protection rights if they are manifestly unfounded or excessive”.

Unsurprisingly, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) raised SLAPPs in its response to last year’s ICO consultation on the code, asking the ICO to address SLAPPs further (paras 16-17).

What next for anti-SLAPP legislation

The forthcoming Economic Crime Act now seems certain to contain anti-SLAPP provisions. Although limited in the first instance, further legislation is likely to follow as the already significant Parliamentary consensus around the scale and importance of this issue – on a range of grounds, notably freedom of speech and national security – continues to build.

However, the responsible regulators do not look to be set up to take on these additional responsibilities. If so, this is not their fault but is due to a mix of inadequate powers, lack of resources, too narrow a statutory scope, a self-regulation culture ill-suited to this role, and (for PIs) the absence of regulation at all. In these circumstances, given the nature and scale of wealth that typically propels SLAPP cases, it is hard to have confidence that the new regulation can be implemented successfully.

The existing regulatory framework was not set up with SLAPPs in mind, so none of this is a criticism. But it still leaves a situation where anti-SLAPP legislation is unlikely to have the effect Parliament intends. At best, courts can identify and stop individual SLAPPs, but the scale of the rewards means that those lawyers, and others, who enable SLAPPs are unlikely to be deterred from trying again.

Impact beyond legal services

SLAPPs are an attack on free speech in the public interest, potentially undermine the UK’s national security, and tarnish the reputation of the City of London and the UK. So they have an impact that goes far beyond legal services. This might open a path for other regulators, in furthering their own objectives, to take account of SLAPPs and coordinate their activity with the legal services regulators.

In particular:

- The inclusion of the anti-SLAPP clauses in the Economic Crime Bill has potential relevance to the FCA’s market integrity objective (e.g. its financial crime and transparency elements)

- The Bank of England has an overall responsibility for the resilience of the financial system, which SLAPPs undermine by seeking to suppress information that helps protect society from economic crime.

- As the “governing body of the Square Mile”, the City of London Corporation has a clear role in protecting the reputation of London’s financial district. “Contribute to a flourishing society” is one of its aims.

As a possible example of such coordination, if a firm of solicitors establishes a reputation for taking cases that are identified as SLAPPs and has been sanctioned by the SRA/SDT, it seems reasonable that the FCA would expect financial services firms to formally seek relevant assurances before considering doing business with them.

Such coordination is always a challenge in practice, and it may also be that the intersection between the powers and remits of the respective regulators is not sufficiently strong to justify such a coordinated response.

But SLAPPs is a big enough issue for all the regulators involved to warrant a serious exploration of what is possible. Perhaps this might be jointly led by the SRA, as the legal services regulator most affected, and the Bank of England, given the breadth of its oversight and convening role.

Gavin Stewart is an independent commentator on financial regulation; former regulator; novelist; ex-international rower and sports administrator. He has 27 years’ experience working for financial services’ regulators (Bank of England, FSA & FCA), holding a wide variety of roles including as a Bank of England Supervisor, FSA Head of Strategy, Planning & Performance, and FCA Chief Risk Officer.