4 March, 2024 by Kate Duguid in New York, Nikou Asgari and Costas Mourselas in London

One of Bill Clinton’s top advisers memorably said that he would like to be reincarnated as the bond market “because you can intimidate everyone”. But in recent years, the most powerful fixed-income market of all has been scaring its own regulators.

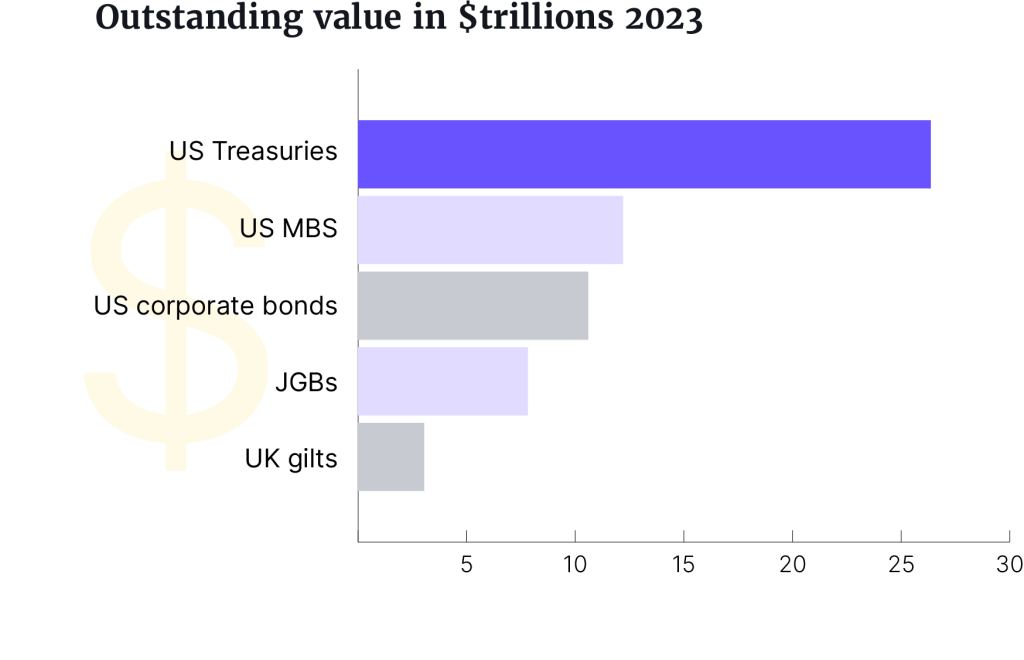

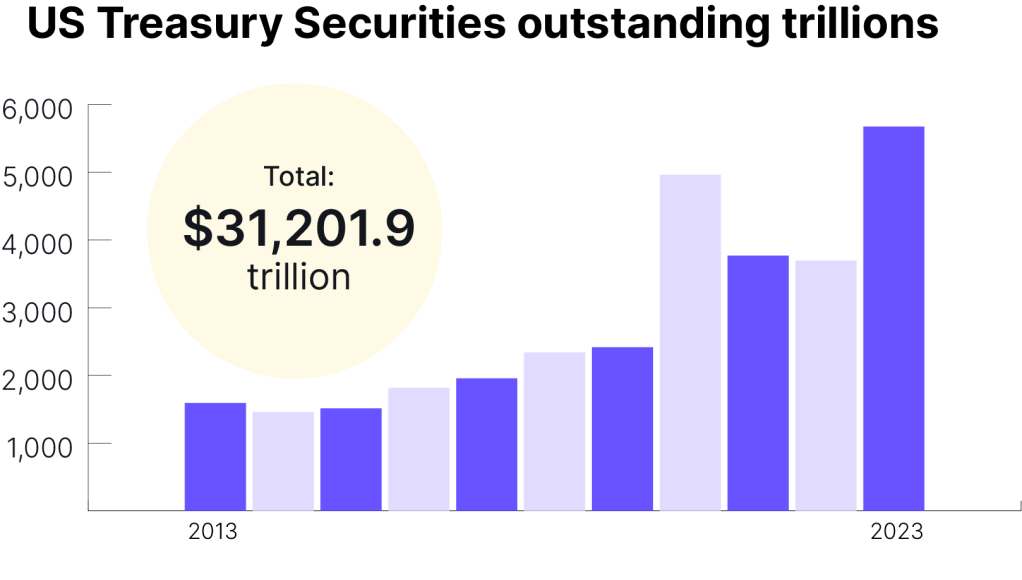

The $26.5tn US Treasury market is the biggest and most liquid in the world and Treasury securities are held by investors and central banks across the globe. The market is the mechanism by which the Federal Reserve executes monetary policy and through which the US government borrows. Yields on Treasuries are the risk-free rate against which assets around the world are priced.

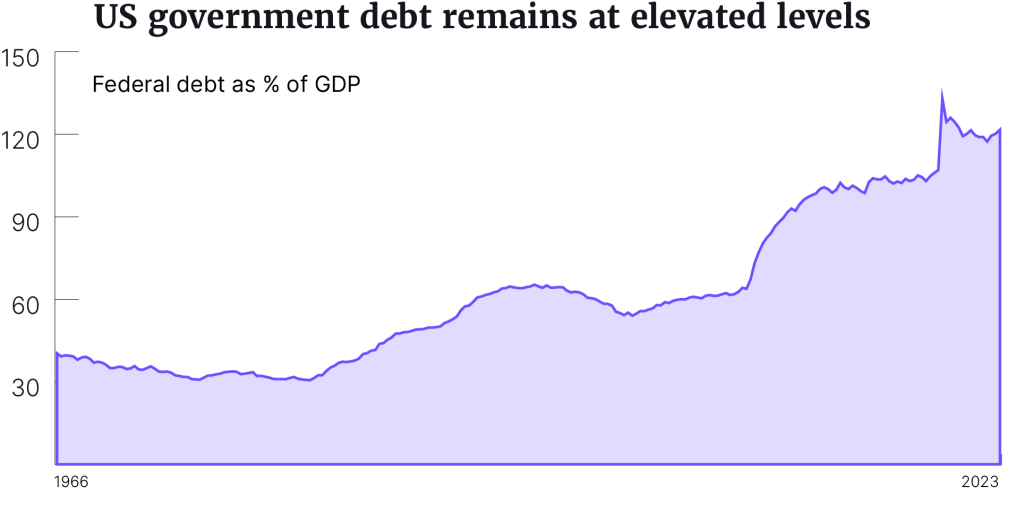

But growing problems could threaten the asset’s supremacy in the financial world. On three occasions in the past decade, crises have precipitated a dysfunction in the market. The 2019 repo crisis and the March 2020 market meltdown required emergency intervention from the Federal Reserve and the New York Fed.

Such strains have pushed the five main government entities that regulate the Treasury market to discuss big changes. The Federal Reserve has enacted programmes to reduce the chances of another repo crisis while the Treasury department has made changes to increase market transparency. But no other major reforms to the market’s structure had been passed until the Securities and Exchange Commission recently finalised two rules that promise to reshape the market.

“The US Treasury market is . . . a really important feature to promoting the dollar’s continued leadership around the globe,” Gary Gensler, the chair of the SEC and the architect of the reforms, tells the FT.

“Having that reliable, safe and readily accessible and tradeable asset is critical. It was critical to the British in their time as the leaders in currency. It was critical to the Dutch before that. This is an important piece of what the Fed, the Treasury and we are doing here,” Gensler adds.

The most consequential of the rules, passed in December, will remodel the Treasury market’s plumbing by forcing more trades through a clearing house. Having a third party behind every deal promises greater oversight and protection for investors and ensures that trades are backed by cash. This collateral aims to prevent cascading defaults during a crisis.

Kevin McPartland, head of market structure at Coalition Greenwich, says the central clearing proposal was “definitely a monumental change for the Treasury market”, adding that enacting it will be a “big accomplishment” for the SEC.

In February the SEC passed its so-called dealer rule, which will bring high-speed traders and potentially some hedge funds under regulatory scrutiny.

“All of these developments are significant steps to make the Treasury market more resilient and ensure it remains the deepest and most liquid market in the world,” says Josh Frost, assistant secretary for financial markets at the Treasury department.

Nate Wuerffel, head of market structure at BNY Mellon and a former head of domestic markets at the New York Fed, says that if the reforms are well executed, “we could be in a world where 10 years from now the Treasury market is even more efficient and liquid than it is today”.

Critics argue that the new rules will impose additional costs, reduce trading volume and concentrate risk in a central clearing house. How exactly the change will be enacted, who will benefit and whether it will bring a host of secondary problems is still unclear.

“If everyone who is subject to the mandate has a workable clearing solution that doesn’t limit who they can trade with or add significant costs that change the economics of trading and reduce liquidity, then it’ll probably be fine,” says Graham Harper, head of public policy and market structure at trading firm DRW.

“But those are big ‘ifs’ and if they’re not solved, it could have serious negative ramifications for the market.”

Clearing houses are a low-profile but vital piece of financial market plumbing. They stand in the middle of a trade, between a buyer and seller, and take collateral from both parties to help guarantee they will deliver the cash or securities they owe. Without a central clearing house, if a bank or big hedge fund fails, the traders that have transacted with them have little recourse to recover their assets.

The new rule will mandate that from December 2025, all purchase or sale trades of Treasuries with broker-dealers or interdealer brokers must be routed through a clearing house, while most repo trades must be cleared from June 2026.

Repo trades entail traders borrowing money using their Treasury holdings as collateral. They give traders access to cash at short notice without having to liquidate their holdings outright. The outstanding US repo trades held by primary dealers were worth $5.7tn in January, according to data from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

“There are lots of operational hurdles, technological and frankly legal burdens that our members are going to have to undertake.”

Nhan Nguyen, Assistant General Counsel, Investment Company Institute

Central clearing is intended to protect investors during crises like those that have affected the market in recent years. It could also help in the event of a cyber attack on a major market player; the FT reported last year that a hack of the financial services arm of China’s biggest bank, ICBC, affected trading in Treasuries and raised concerns that traders might not receive the bonds they were owed.

But market participants say this monumental change to the Treasury market must be managed well, or it risks damaging liquidity and even operational security. They will have to set up new systems in order to be able to clear their trades.

“There are lots of operational hurdles, technological and frankly legal burdens that our members are going to have to undertake,” says Nhan Nguyen, assistant general counsel at the Investment Company Institute, which represents investment funds. He adds that there is “a bit of a feeling of the cart before the horse”, about the rule.

Many traders’ costs will increase, as they will need to post cash as collateral to protect against defaults and pay fees to the clearing house. Banks may shield their largest clients from some of these costs, but one way or another they will filter through.

The requirement to post collateral can also be viewed as a cap on leverage. Currently, over 70 per cent of non-cleared Treasury repo trades with just two parties occur with zero margin to cover the risk of the trade, according to the Office of Financial Research.

This means that if a bank lends cash to a hedge fund in exchange for temporary ownership of a Treasury bond, and the value of the bond decreases just as the hedge fund defaults on the trade, the bank loses the cash it has lent and takes a loss when it sells the collateral.

Introducing some cash margin into repo trades will help protect banks and other counterparties who lend in this way, but reduces the amounts hedge funds can borrow.

“The cost of that risk management will get embedded in the . . . price at which the market trades and the liquidity of the market,” says BNY Mellon’s Wuerffel. “And it will mean that those costs are slightly higher and liquidity is slightly lower in normal times, in order to create the capital and the risk management systems that are necessary in times of stress.”

This will affect strategies such as the controversial basis trade, where hedge funds bet on the price differential between Treasury futures and cash Treasuries narrowing using borrowed money.

The leverage deployed can be enormous — in some cases more than 100 times — and regulators fret that it could result in a flash crash in prices if multiple hedge funds were forced to close out their positions simultaneously. In the final central clearing rule, the SEC flagged worries over hedge fund leverage in the market and how it could impact their banking counterparties if these bets go wrong.

An executive in prime brokerage at a large US bank says he is relieved margin will now be baked into every trade as without a de facto limit on leverage, banks can only reduce their risk profile by forsaking business. “It’s very hard to move away from [zero margin] unilaterally,” the executive says.

Regulators hope that by making markets safer, traders will transact with greater confidence, generating additional interest in the Treasury market and improving liquidity. Cleared trades backed by collateral would also be lighter on a bank’s balance sheet, theoretically lowering the cost for banks to facilitate this kind of business.

While introducing a central counterparty to guarantee trading brings lots of benefits, including efficiency and reliability, it also introduces a huge single point of potential failure. Clearing houses might help contain the effects of a cyber attack on a market participant, but if the clearer itself is targeted it could bring the Treasury market to a standstill.

The main body for clearing Treasury trades is the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation. But at present just 13 per cent of cash Treasury trades pass through it, according to the Treasury Market Practices Group, while 19 per cent involve one side of the trade being centrally cleared and the other bilaterally cleared. Only 20 per cent of repo transactions are cleared through the FICC, according to the Federal Reserve.

Mandatory central clearing will push trillions of dollars worth of daily trades through the FICC, which is owned by the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation. For DTCC, which also clears equities, the move will greatly increase its current business, cementing its position at the heart of the debt market and earning it juicy fees.

“It’s a single point of failure . . . that’s obviously always a concern,” says Nguyen of the Investment Company Institute, who is worried about the FICC’s ability to handle the increased trade flow.

“The biggest obvious winner is the clearing house and at this point it’s only DTCC through FICC,” McPartland adds.

But the FICC is unfazed by the challenge ahead.

Laura Klimpel, general manager of the FICC, says the venue is preparing for an “incremental ramp up as opposed to a massive transformation of what we do today”.

The clearing house is scaling up its systems by adding extra hardware and making some processes more streamlined. Klimpel adds that she recognises the “sacred duty” of the venue to protect the market “and do whatever we can to ensure its smooth functioning”.

The SEC has given the FICC until mid-March to fully flesh out how it will deal with the overhaul and the trillions of dollars of debt trading business set to head its way.

But the FICC’s own dominance may be shortlived. Many participants expect a fiercely competitive battle to begin for the lucrative business of clearing in such a vast market. Competition would also help address concerns about the outsized importance of New Jersey-based DTCC in clearing.

“Their role is going to be pivotal until there’s some competition in that space,” says one senior exchange executive. “All of the equities clear at the NSCC division of DTCC, now they want to be the default utility and win everything in the world of government securities and repo,” the executive adds, leaving the company’s domination of US markets “too great.”

Exchanges such as Chicago’s CME Group and New York Stock Exchange owner Intercontinental Exchange, which both run derivatives clearing houses, are considering entering the fray, according to people familiar with the matter.

ICE is “in active dialogue” about a potential move, one senior exchange executive says, adding that the venue has a platform it “would be able to lever [if they] can do it in the right way”.

CME and ICE declined to comment.

Traders hope that competition will push down costs and reduce the risk of funnelling all deals through one venue. “Ideally, it wouldn’t fall on just one clearing house,” says DRW’s Harper. “I think there is a good chance that at least one competing clearing offering could show up between now [and 2025],” he adds.

Gensler says the SEC is “open to competition.”

The SEC’s efforts to introduce central clearing come as the agency faces a slew of legal challenges over some of its other reforms. It is unclear whether the Treasury market proposals will attract lawsuits in the same way as the rules over private funds and short selling.

The industry has not yet telegraphed any intention to go to court, but many details will not be determined until FICC outlines its own policies next month.

Opposition may be more focused on the SEC’s “dealer rule”. This will force high-speed trading firms and potentially some hedge funds to register with the agency as dealers, obliging them to be more transparent about their positions and trading activity, hold more capital and join a self-regulatory organisation such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Association.

Bryan Corbett, president of the Managed Funds Association, a hedge fund industry group, said the two rules “will change incentives for private fund ownership and trading of Treasuries — the foundation of the global financial system.”

He described them as “ambiguous” and predicts they will “discourage investment, harm liquidity and market efficiency, while increasing market volatility”.

But Gensler stressed that the dealer rule is “primarily about principal trading firms”, rather than hedge funds.

He noted that the SEC had been challenged on just six of 34 rules adopted during his tenure.

“Now on the other 28, maybe we’ll get a challenge or two,” he says. “But, we’ve been very conscious and attentive to what is the law and how are the courts are interpreting the law.”

Gensler adds that he feels “very confident” about the specifics of the Treasury market rules, while acknowledging that “part of our democracy is people can go into court and take these in front of a judge”.

“If something gets remanded, we adjust and we pivot and we move forward.”

© The Financial Times Limited 2024. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.