18 January, 2024 by Cynthia O’Murchu and Robert Smith

In October 2019, hundreds of wedding guests flew in from around the world to the grandest resort on the French riviera, the Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc. But this was to be no ordinary stay at the pleasure palace immortalised in F Scott Fitzgerald’s novel Tender is the Night. The groom had rented out the entire resort, paying exorbitantly for the five-star hotel to reopen after its summer season officially ended. The privacy of his guests was more than assured.

As the gathered stepped out on to the terrace with their drinks, they saw not only the vast azure plain of the Mediterranean, but also the groom’s 240ft-long superyacht on the horizon. By the end of the night, Lionel Richie, Craig David and Lenny Kravitz had all serenaded the newly-weds. The wedding’s unstated theme was excess, but the groom was not worth billions. He owed billions.

Lars Windhorst, then just shy of 43, had spent three decades in the public eye. As a teenager in the 1990s, he was hailed as a wunderkind of German business before enduring a downfall that included the collapse of several ventures, personal bankruptcy and a criminal conviction. He only managed to avoid prison by co-operating with authorities. In any conventional cautionary tale, that would have been the dramatic conclusion, the final humbling. In any conventional tale, Windhorst would not have been in a position to be feted.

But in the decade between his conviction and the wedding, Windhorst rebuilt his fortune. Then recklessly imperilled it and survived again. His talent for financial escapology earned him a reputation as a consummate survivor. The wedding’s guest list alone was a testament to that fact. Rubbing shoulders with sports stars and entertainers were some of the biggest names in global finance.

The real VIP in attendance was no celebrity. Bruno Crastes, a tall, tanned and silver-haired Frenchman in his mid-fifties, had an uncanny talent for making bets on bond and currency markets that had made him a fortune. His investment firm, H2O Asset Management, was responsible for more than €30bn of investors’ money. Crastes’s Midas touch drew in everyone from everyday savers in France and Italy to private wealth managers in Geneva and Seoul. Some of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world had entrusted him with billions of dollars.

Crastes was more than just another luminary drawn to Windhorst. In a sense, it was his investors’ money that had made the lavish event possible. Crastes’s largesse was no secret. Months earlier, the Financial Times revealed that his firm had poured nearly €1.5bn into Windhorst ventures. Investors panicked, yanking billions from H2O’s funds. But Crastes showed little sign of strain, dancing near the front of the stage. And yet, events had been set in motion that, within three years, would push H2O to the brink and destroy Crastes’s reputation. The punishment for his relationship with Windhorst would be record-breaking and long-lasting. Regulators continue to pore over what really happened. The scandal would leave the world of high finance struggling to comprehend why one of the finest fund managers of his generation ignored his closest confidants and bet on a man with a visible trail of wreckage behind him.

Bruno Crastes rose to address the courtroom. It was 1998, and the 32-year-old was already a rising star of French finance, overseeing a team of traders in Paris. But a family tragedy had wrenched him back to his hometown of Lyon.

Crastes’s austere upbringing had offered no shortcuts to a career in finance. His father was a jeweller and his mother a hairdresser. They had an unhappy marriage that ended in divorce. Bruno’s older brother Norbert frequently provoked their father’s violent temper, earning him a beating with a whip. In contrast, the younger Crastes was diligent and well behaved.

Bruno’s flair for maths won him a spot at the University of Lyon, and he later qualified as an actuary at a respected local institute. One classmate there remembered Crastes as a “very hard-working” young man, who was “quite discreet, reserved and serious”, and yet still a good friend. “In retrospect, he was more mature than we were,” the classmate said. Even then, Crastes possessed a beguiling self-assuredness. In a class photo from the late 1980s, he sits in the front row wearing a black turtleneck, flashing the confident smile that would seal deals with wealth managers around the world.

Crastes went into finance after graduating in 1988, during the rise of a new breed of trader, the macro hedge fund manager, who profited from anticipating the fluctuations of currencies and interest rates. The approach required a strong stomach for risk, which the young Frenchman possessed in spades.

Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Back in Lyon, Crastes’s father had died of cancer and his older brother had spent his adult life in and out of psychiatric facilities. When Norbert was on release, he lived in a cramped apartment with their mother, who dedicated herself to his care. Over the years, Norbert grew to resent his successful sibling, grousing that Bruno had always been the favourite. Then, in January 1996, Norbert murdered his mother.

He claimed that hallucinations had driven him to commit the crime. But at trial, experts agreed that his mental faculties were intact. If jurors harboured any doubts, Bruno soon dispelled them. He faced his brother, who sat silently in the courtroom. “Norbert is a coward. He’s not brave and has never wanted to face real life,” he said, painting a picture of a selfish freeloader, frittering away borrowed money. “He’s not a victim. He had every opportunity to live a normal life,” he continued. “Our mother gave him her life. It’s true that he’s ill, but he likes himself the way he is. His illness is a good excuse.” Norbert was later sentenced to 15 years in prison.

In 1999, Bruno Crastes left France and what had happened there behind. He moved to London to help set up a new branch of French bank Crédit Agricole’s asset management division. He settled in South Kensington, an enclave for well-to-do expatriates. For many French traders in London then, the world of Anglo-Saxon finance could feel liberating. Crastes excelled by combining a deep knowledge of global markets with personal magnetism. “You get these brilliant people who could be geeks,” one colleague from this time said. “But Bruno also mastered the language of charisma.”

With clients, he projected supreme confidence, sharing quotable maxims as if he was imparting valuable secrets. And when markets moved against him, Crastes betrayed little concern. “If you are not able to get poor, you will never get richer,” he explained with a smile.

Crédit Agricole bestowed ever grander titles on Crastes. Sat in the middle of a cavernous trading floor in a building located near the Bank of England, Crastes struck some visitors as looking like a king at court. But his team tended to see him differently. “If you knew Bruno back then, he was not an arrogant guy,” said another former colleague, noting that he encouraged juniors to question every line of his portfolio.

Crastes’s investment philosophy could be summarised in two words: don’t panic. When others were losing their heads, he loaded up on risky assets. The formula worked. By 2007, his team oversaw tens of billions of dollars. When it came to the brewing US subprime mortgage crisis, Crastes thought doomsayers were getting ahead of themselves. “This is something that shouldn’t damage the state of the real economy,” he predicted in the summer of 2007. It was a catastrophic miscalculation, made worse by his team’s extensive use of leverage, which exacerbated losses in a downturn. As his funds cratered and investors stampeded for the exits in 2008, Crastes looked like yet another trader who blew up his future by taking outsized risks.

Crastes’s investment philosophy could be summarised in two words: don’t panic. When others were losing their heads, he loaded up on risky assets.

He held his nerve, however, and positioned his investments for a rebound. Investors had pulled some €30bn from his team’s funds during the panic, but loyal clients were rewarded by the recovery the following year. Among European investment consultants, that cemented Crastes’s legend.

After regaining momentum, Crastes struck out on his own in 2010, with Crédit Agricole rival Natixis staking his new fund-management venture. Natixis, a co-operative bank, had never been known for stringent risk controls and, though it owned a majority, wouldn’t interfere with Crastes’s day-to-day decision making. His real partner would be Vincent Chailley, Crastes’s longtime deputy.

The son of a doctor, Chailley’s career path to finance ran through the typical French route of earning distinguished maths diplomas from grand Parisian universities. He possessed a haughtier air than Crastes, despite being seven years his junior. Chailley often wore spectacles under his thick mop of brown hair and had a fondness for expensive suits and Berluti lace-ups. He also carried himself with the confidence of someone who believes that they understand how markets work better than almost anyone else.

Chailley did not share his boss’s knack for explaining complicated trading strategies, but the two men were unified by their affinity for risk. Like Crastes, Chailley could be eerily placid in a crisis, calmly steering the trading desk when markets seemed to move without reason. Colleagues noted he sometimes got nosebleeds when losses began to mount, but otherwise seemed unbothered.

When it came to the intricacies of constructing investment portfolios, Crastes considered Chailley a savant. He’d taken Chailley under his wing and moulded his investing style. To colleagues, the pair gave the impression of an older and younger brother, at times playful and boyish, despite the billions at stake.

Crastes made Chailley his chief investment officer and handed over a large stake in the new firm, which he christened H2O. The name was a reference to liquidity — assets that can be easily traded for cash — and transparency. Both were crucial because ordinary savers would be able to invest with H2O. Charging the high fees typical of private funds to a mass market could be vastly profitable. But it meant H2O’s flagship funds had to comply with rules intended to protect so-called unsophisticated investors.

In 2011, about 10 people began trading out of a sparse room in the corner of Natixis’s London offices next to the river Thames. The junior staff joining H2O found Crastes was no aloof master of the universe. While he refrained from discussing the tragedy in his past, he did little to hold back his affection for the new family he had started.

H2O’s first year was a white-knuckle ride, after a bet on Greek government bonds racked up losses. But the French traders scraped through, and towards the end of 2011 moved across town to an office in Mayfair. Crastes and Chailley did not know it yet, but another consummate survivor had recently set up shop barely 150 metres around the corner.

One minute past 3am on Boxing Day 2007, the control tower at Almaty airport cleared a Bombardier Challenger for take-off. The private jet had arrived in Kazakhstan from Germany several hours earlier, in need of refuelling. A light layer of dry snow covered the runway as the plane attempted to ascend into the misty night sky. Instead, it tilted right, its wingtip hitting the runway edge, sending the jet hurtling into the airport’s reinforced fence. By the time the aircraft came to a halt, it had split into three pieces, and its fuselage was engulfed in flames. One of the co-pilots died instantly. The only passenger, a 31-year-old Lars Windhorst, lay unconscious in the snow.

He was airlifted to a Berlin hospital, having suffered a severe head injury, broken ribs and a partly severed right ear. His flair for splashy dealmaking remained intact, however. Just over a week after the crash, the firm Windhorst ran at the time announced that it had become the largest single shareholder in Air Berlin. The market applauded, sending shares up 10 per cent. Cheating death was just another work day in the life of Lars Windhorst.

German chancellor Helmut Kohl had catapulted Windhorst to fame in the 1990s, when he was still a teenager running a computer distributor from his parents’ garage. Kohl plucked him from the rustic West German town of Rahden for a grand tour of Asia, where the young man met with business leaders and heads of state. Windhorst’s success captivated a recently reunified country yearning for a youth-driven economic renaissance. Before long, the national press dubbed him the German Bill Gates. The prodigy was unimpressed with the comparison, complaining: “At 16, [Bill Gates] didn’t have his own company.”

Windhorst became a Zelig of financial booms and busts. In the late 1990s, he touted plans for “Windhorst Tower”, a 55-storey-tall skyscraper project in Ho Chi Minh City that crumbled during the Asian financial crisis. After the dotcom bubble burst in the early 2000s, Windhorst Electronics went bust. Windhorst was back a few years later, spearheading investments in buzzy stocks but, when the 2008 crisis hit, another bankruptcy followed.

In 2009, German prosecutors brought fraud charges against Windhorst. A healthcare entrepreneur alleged he had duped him into providing a loan by claiming that a windfall investment from the family fortune of a deceased African dictator was imminent. That winter, Windhorst strode past a blizzard of camera flashes to face justice. He cut a deal with prosecutors, pleading guilty to a lesser charge of breach of trust in exchange for a suspended prison sentence. At a later hearing, Windhorst admitted through gritted teeth that he had misappropriated company funds.

But Windhorst was already trying his luck in a new town. He set up shop in London around the time of the trial. While his financial resources were greatly depleted, he still possessed a Rolodex of high-powered contacts. Over the decades, Windhorst’s network grew to include everyone from reformed junk bond king Michael Milken to Hollywood A-lister Michael Douglas, who happily posed for photos with Windhorst long after his film production company joined the ranks of the financier’s creditors. This uncanny ability to win back the trust of those he burnt became one of his hallmarks. Even the businessman who set in motion Windhorst’s criminal conviction eventually invested with him again.

Those meeting Windhorst for the first time in London in the early 2010s found he had retained a disarming boyishness. Rather than trying to hide his past, he drew people in with tales of scarcely believable ups and downs. The subtext was always: Lars Windhorst can survive anything, even a plane crash. “He used it as evidence of his resilience,” said a former business associate. “Back then when you googled his name, you’d see a picture of that plane wreck.”

By 2012, Windhorst was ready to return to the limelight. His vehicle for doing so was an investment firm called Sapinda. Windhorst rented the top floor of 23 Savile Row, paying rates that made it the most expensive office leasing deal in Europe that year. It was just one of many accoutrements Windhorst amassed to illustrate his financial resurrection, including a superyacht, helicopter, jet and luxury apartment at One Hyde Park.

Windhorst’s true talent was loosening purse strings. In a world of rock-bottom interest rates, he found that fund managers were more willing to entertain unconventional investment opportunities if the returns were high enough. The conviction in his rapid-fire pitches was infectious enough to make even blue-chip asset managers look past the underlying companies’ skimpy balance sheets. Windhorst’s carefully attuned sense of people’s motivations and desires handled the rest. “You have to develop an understanding of what’s going on in other people’s heads and adjust to it,” he once explained. Still, while mainstream fund managers began to dabble in Sapinda’s bond deals, none were willing to go all in. If Windhorst was going to finally be recognised as a serious dealmaker, what he really needed was a whale.

Vincent Chailley could hardly contain his excitement. Bounding into H2O’s Mayfair offices one day, he began regaling colleagues with the captivating tales of the financier he’d just met. As he spoke, Crastes pulled up the details of Windhorst’s past on his computer in disbelief. “Vincent, he’s been bankrupt twice,” one former colleague remembers Crastes admonishing Chailley around 2014. “Don’t put any of his stuff in my funds.”

Some H2O traders wondered if H2O’s chief investment officer had been mesmerised. Chailley would regularly walk around the corner for lunch at Windhorst’s office, where a chef served three-course meals in an elegant private dining room. “They would hug,” a former associate of Windhorst recalled. “I wouldn’t say it was a business relationship. It was more buddy-buddy.”

In April 2015, H2O invested in bonds funding Windhorst’s businesses for the first time. Even if Chailley seemed caught up, he went into the deals cautiously, warning a colleague that the financier had a “finger in the air” approach to valuations. But Chailley was not prepared for how quickly things began to go haywire.

The plan was for H2O to make easy profits when Windhorst bought chunks of bonds back shortly after selling them. Instead, the trade failed to settle on time. A few weeks after investing, Chailley found himself chasing Windhorst for payment, warning over emails seen by the FT that “the issue is getting serious”.

“As this took longer and created unexpected headaches for you, I would like to pay you more,” Windhorst wrote back. “Please let me know which number would make you happy.”

It took more than a month for H2O to finally receive payment, an early taste of what lay ahead. Regardless, Windhorst continued to pepper Chailley with invitations to private dinners. The proposed guest lists included several men who would later be accused of financial crime, including Mohamed al-Husseiny (implicated in the notorious 1MDB fraud and since imprisoned in Abu Dhabi) and Arif Naqvi (now facing extradition to the US for allegedly defrauding investors).

Crastes and Chailley declined to comment for this article. Windhorst told the FT that he had maintained an “extensive global network of relationships” since he was 16 and “never hesitated introducing people to each other obviously not knowing how those people or the relationships would develop and evolve later on”.

Crastes’s qualms melted soon after he met Windhorst in London in the summer of 2015. Soon, the financier invited Crastes to spend three days travelling around the Mediterranean on his superyacht, Global. The itinerary for the long weekend they spent together that August was intricate, with Windhorst’s jet and helicopter on hand to ferry his guests to and from the boat. Keenly aware of the H2O founders’ reputation as family men, Windhorst made sure to include Crastes’s and Chailley’s loved ones.

If Windhorst hoped to dazzle Crastes, it worked. After the trip, the Frenchman sent an email, thanking the financier for the “memorable days we spent together”. “We sincerely enjoyed each moment and every conversation,” Crastes wrote. “All was beauty and elegance.” In a sense, Crastes and Windhorst were kindred spirits. Both saw themselves as outsiders, who thrived on risk and favoured trusted relationships over convention. But as Crastes supplanted Chailley as the object of Windhorst’s charm, H2O’s number two became the one warning about the risks. “We’re starting to have a lot of engagement with Lars, and I don’t think the turn we have taken is right,” Chailley wrote to Crastes in September 2015, noting that aside from the various payment issues on his bond trades, a promised $10mn investment in one of H2O’s funds never materialised. Each time he was asked about it, Windhorst came up with “a different excuse”.

Over the course of 2016, Chailley tried to hide the growing strain from his colleagues. But he was at times betrayed by the blood dripping from his nose. The trickle of issues with Windhorst had turned into a flood. Chailley could not shake the sinking feeling that H2O had been taken for a ride.

At the start of that year, Windhorst had been touting an investment from an Emirati royal that would solve all his repayment problems. As it became clear that deal was never going to happen, however, he was reduced to begging H2O to help bail out Sapinda. “I am 100% certain and completely sure that it is in the best interest of H2O . . . that we one last time co-operate closely in this very special and very difficult situation which is so close to a positive turnaround,” Windhorst wrote to Chailley and Crastes in December 2016.

Legal problems were already mounting. By early 2017, half a dozen creditors had filed lawsuits against Windhorst or Sapinda, alleging they were owed more than €200mn. His adversaries included formidable characters such as a Russian oligarch who had served as energy minister under Vladimir Putin.

Chailley had seen enough. “Lars’s world is really a beautiful rotten world,” he wrote to Crastes in April. “No common interests. Just liar’s poker.” The magic seemed to be wearing off for Crastes too, who texted Windhorst: “My legal team also told me that some previous documents you sent us were fake. We are at the end of the road and we have no way out.”

Chailley drew up a plan with H2O’s risk and compliance department to launch its own lawsuit against the financier. But when they presented their proposal to Crastes in the summer of 2017, he refused. He had experienced a sudden change of heart and was now convinced working with the financier offered H2O a better chance to make its money back. Chailley was in disbelief. He was also exhausted and headed off for a long summer holiday, in effect handing over control to his mentor. Shortly after, Crastes made the decision that inextricably tied his fortunes to Windhorst.

Windhorst seemed to be at his nadir. He had even been ousted from his own company, after one hardball creditor seized his stake in Sapinda. But H2O agreed to loan Windhorst hundreds of millions of euros through a new investment vehicle called Chain Finance. That would give him the financial firepower to wrest back control of Sapinda and start settling creditor claims. H2O was loading up on new Windhorst bonds that would be difficult to unload in a moment of crisis, an “illiquid” investment in market parlance. This ran directly counter to the firm’s foundational principles. And because H2O’s funds were open to everyday investors, regulators placed strict limits on how much money could be put in hard-to-sell assets — raising the overall jeopardy.

The mystery of how Windhorst had convinced Crastes to look past these obvious risks was endlessly debated by H2O insiders. His defenders would have noted it had all the hallmarks of a classic Bruno trade. He had scored some of the biggest wins of his career by coolly doubling down when everyone else was panicking. Why should Windhorst’s crisis be any different? But there was more to it. “Bruno was fascinated by Lars,” said one person who observed the two men’s relationship. “And even though he knew he wasn’t perfect, he thought what was being done to Lars was unjust.” Another person in the German’s orbit, who was present during the Mediterranean trip that first cemented Crastes and Windhorst’s bond, was more scathing, arguing that the H2O chief had given “himself up on a gold platter”.

In the final days of 2018, Windhorst’s superyacht criss-crossed the Caribbean, then nestled alongside dozens of other enormous vessels assembled for New Year’s Eve on the shores of St Barts. Windhorst rang in the new year with the two most important people in his life: his fiancée, Christin Bahla, and Crastes. The H2O chief, along with his wife and children, had escaped the dreary European winter for a week in the tropics. As they arrived in Saint Martin for their flight home on Windhorst’s private jet, Crastes dashed off a message thanking their host for the “week of dream” they had spent together. “We feel like having a new family with Christin and you,” he wrote. “And it goes straight to our heart.”

Family. Windhorst was aware of the tragedy in Crastes’s past and likely knew that the word had added weight for the Frenchman. “I feel exactly the same,” Windhorst wrote back. “It’s more than just close friendship between us. It does feel like extended family for me also!”

The Caribbean was a picture-perfect ending to the most successful year of Crastes’s career. He had smashed the lights out yet again, notching up annual returns of more than 30 per cent for the fourth time since founding H2O. By the end of 2018, H2O’s assets under management swelled past the $30bn mark. The firm’s profits doubled year on year to exceed half a billion dollars. Crastes would be giving a smaller slice to the taxman though. He had relocated from London to Monaco, the European tax haven that Somerset Maugham once dubbed “a sunny place for shady people”.

Crastes’s family settled into an apartment overlooking the Plage du Larvotto, and he spent his time trading from H2O’s new Monaco office nearby. The move caused consternation among some H2O executives, who feared the distance would fray the closely knit team. Brexit had already pushed it to shift some staff to Paris. The esprit de corps that had distinguished H2O when everyone sat in the same room was lost.

Crastes had scored some of the biggest wins of his career by coolly doubling down when everyone else was panicking. Why should Windhorst’s crisis be any different?

Some at H2O wondered if Windhorst had drawn Crastes to Monaco. The German financier had long been a fixture there, with Sapinda sponsoring equestrian events that allowed him to rub shoulders with Monaco’s royal family. Windhorst offered to open doors for Crastes in the principality’s high society, dangling invites to events such as wine tasting with the prime minister. As his relationship with Crastes deepened, Windhorst sometimes requested H2O help “clean” the balance sheets of his companies before they were presented to auditors and other third parties.

Chailley watched the financial acrobatics with growing alarm. In February 2018, he emailed Crastes complaining that Windhorst “continues to leverage himself on our balance sheet”. Chailley went on: “He had promised in writing to put us in the loop on any of Chain [Finance]’s expenses, which he did not honour. We really have to do something.” Chailley’s concerns proved well-founded when it later emerged in court that Windhorst was billing everything from private jet expenses to charges at luxury hotels to companies that H2O had backed.

By November, Chailley could no longer tolerate the risks. “As you know, we have in excess of €600mn unsettled trades with Sapinda in our books since August 2017,” he wrote to Windhorst. Chailley issued an ultimatum: pay up and settle the trades, or forgo further investment. Nonetheless, days later members of the H2O investment team found themselves discussing whether to buy into a new bond deal backing a speculative oil venture from Windhorst. Chailley summarised the case against the deal for his colleagues: “To subscribe to LW’s hidden agenda would be dangerous for us and makes no sense from an investment perspective.”

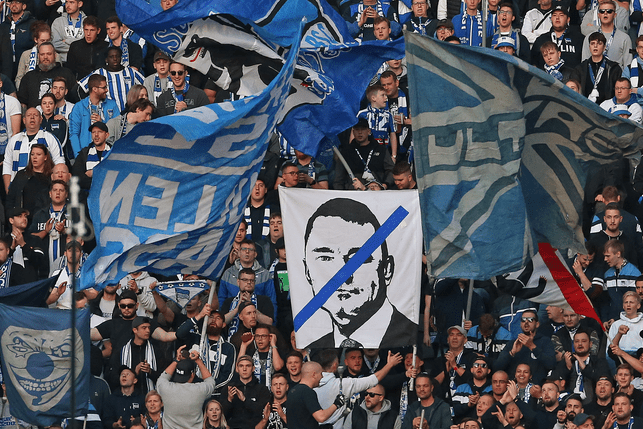

Around the time of Crastes’s holiday with Windhorst, however, he agreed to invest in the deal. Armed with H2O’s cash, Windhorst’s plans became even grander. He began to plot a takeover of Hertha Berlin, a more than century-old Bundesliga football club. Windhorst thought he could restore the team and his reputation in Germany in the process. But Sapinda was synonymous with scandal. So in May 2019, Windhorst announced that his firm was rebranding as Tennor Holding and unveiled a new advisory board of heavyweights from the world of finance including, naturally, Bruno Crastes.

By then, Chailley’s concerns were becoming unbearable. That month he sent Windhorst an email explaining that H2O could not proceed with an investment in a new bond deal from Tennor because it breached the level of illiquid exposure allowed by the rules. Chailley estimated that, though H2O’s maximum allowed exposure to Windhorst’s bonds was €1bn, it was in fact more than €1.5bn. “Confidence,” he later wrote, “takes long to build but unfortunately vanishes quickly.”

Six days later, in June 2019, the FT published the investigation exposing how H2O built up its exposure to the hard-to-sell Windhorst bonds. When the stock market opened on June 20, shares of H2O’s parent company Natixis plunged. In a video message filmed in H2O’s Paris office, Crastes assured clients that Windhorst was not the “sulphurous character” portrayed in the newspapers. Crastes was relaxed, even jovial at times, as he brushed off the scandal. Speaking in mellifluous French, he assured investors his ties to the financier were “purely business” and that there was “no question about the liquidity of H2O”.

Chailley was more agitated. He had spent much of the previous year issuing strident warnings about H2O’s exposure to Windhorst, but when a newspaper exposed the same problems, his loyalty still belonged to Crastes. The scale of their crisis quickly became clear, as H2O investors withdrew nearly €8bn over the course of eight trading days.

Crastes knew strong words had the power to halt market panics. “We never gated and we will never gate,” he declared in a second video to investors, promising not to halt withdrawals. The contrast to Crastes’s earlier address was stark. This time he sat stiffly next to Chailley in H2O’s London office, speaking in halting English and shifting between moments of solemnity and flashes of emotion. But it worked. The rush of investors heading for the exit slowed.

Chailley could not sleep at night. His years playing the role of Cassandra had been vindicated. There was little comfort in being proven right. Running H2O’s funds had always been a high-wire act. But the added strain of intense public scrutiny of their illiquid investments was too much. It didn’t help that he felt his mentor and supposed business partner had cut him out.

In late 2019, Chailley sent Crastes an email, warning that his health was suffering and that he could not “physically stand” the pressure. “You’ve been making important decisions for two and a half years without even consulting me,” he wrote. “We all have our red lines, you have mine.”

Tensions between the two men were rising just as Windhorst’s wedding drew near. Unlike Crastes, Chailley had turned down the invitation. Crastes waved off questions from colleagues about the wisdom of attending given the recent controversy.

While the wedding served as another demonstration of Windhorst’s gilded life, behind the smiles the celebration was in effect a creditors’ ball. Windhorst owed millions to numerous guests. He did not even technically own Global, the superyacht whose horn sounded out when he kissed the bride. Years earlier, the investment firm of a Kazakh billionaire to which Windhorst owed money had taken over the vessel, quietly leasing it back to him.

A few weeks after his opulent nuptials, Windhorst was in dire need of another cash infusion. He jettisoned the usual tact and charm, sending an email that opened: “URGENT AND MOST IMPORTANT PROBLEM.” Windhorst needed €99mn to consummate his investment in the Hertha Berlin football club and painted a picture of the dire consequences if he did not wire the cash by the close of an official deadline that day. “We will have immediately a wave of articles if Tennor is insolvent,” he wrote to Chailley. “There will be investigative journalists looking into everything . . . ”

Chailley was incandescent. Windhorst had “cornered” them, he argued to Crastes, describing the request as being “on the verge of threat”. Rather than complying, Chailley suggested they should “threaten him in return”. Crastes ignored his deputy. Instead, H2O carried out new trades that in effect advanced Windhorst the bulk of the money by that afternoon.

Windhorst had spent months telling H2O he would repay hundreds of millions of euros. Instead, the firm’s exposure to his businesses increased to about €2.5bn. “I don’t know what to call it other than a series of blatant lies that hide a serious solvency problem that will jump out at the sight of any sensible first observer,” Chailley wrote to Crastes at the beginning of 2020, angrily accusing him of “now giving me the shitty stick”. Crastes shot back that Chailley was sending “incessant” emails in a bid to “clear” himself. H2O had to “avoid any confrontation with Tennor”, he argued, or face “disaster”.

“We have to enjoy the party,” Crastes told the audience of investment professionals and wealth managers in Mannheim. He exuded confidence as he preached his gospel of risk taking. “Everything is supported,” Crastes explained to conference attendees, because markets were awash with “excess liquidity”.

It was January 2020, and Crastes was coming off another year of proving doubters wrong. Not only had H2O weathered the controversy surrounding its illiquid investments, but Crastes had yet again made returns of more than 30 per cent. Some of the other fund managers on stage that day expressed concerns about the new strain of virus in China, but Crastes did not concur. “We believe, in terms of macro, that it’s going to be quite boring,” he said.

Six weeks later, international markets crashed. It was a rerun of 2008. H2O’s use of leverage magnified losses and, by the time the market closed on March 9, Crastes’s fund had lost 20 per cent of its value in a single day. That evening, Crastes strolled across Mayfair to a private members’ club for a dinner hosted by Windhorst. The star guest was Gerhard Schröder, the former German chancellor. When Crastes was called on to give his expert view on the outlook for global markets to the others sitting around the table, he spoke with his usual conviction. Days later, one of the fellow guests was shocked to read in the paper that Crastes’s funds had in fact cratered.

“I don’t know what to call it other than a series of blatant lies that hide a serious solvency problem that will jump out at the sight of any sensible first observer.”

2020 note from Chailley to Crastes

The plunge heaped pressure on H2O’s illiquid asset problem. As the value of its mainstream investments fell, the toxic Windhorst bonds made up a bigger and bigger proportion of the funds. Crastes now turned to Windhorst for help. The two men drew up a deal by which Windhorst would buy his illiquid bonds back from H2O at a deep discount, providing a clean exit. But Windhorst needed to raise €1.25bn from investors, who grew increasingly nervous about the potential for regulatory scrutiny. Then, on a Friday evening at the end of August, H2O made an announcement that jolted investors: it had suspended withdrawals in its flagship funds after the AMF, the French financial regulator, raised concerns. Barely a year had passed since Crastes pledged he would “never gate” investors’ funds. Now their money was frozen.

Lauriane Bonnet folded her arms. The AMF prosecutor’s patience was beginning to fray. It was the morning of November 25 2022 and, midway through the French watchdog’s enforcement hearing against H2O, Crastes had walked out. “Medical reasons,” a member of his team offered meekly.

“Shame that he left the room as it would have allowed him to understand that the consequences were grave,” Bonnet said. Minutes later, Crastes came back to the basement conference room, where the prosecutor had laid out the case against H2O, Crastes and Chailley. Crastes’s confidence had steadily ebbed as the proceedings wore on. Now he placed his hands on his forehead, as if to shield himself from what would become the defining moment of his career. Next to him, Chailley sat, back erect, almost defiant.

The room was quiet as Bonnet announced the AMF’s recommendation: a €75mn fine for H2O, €15mn for Crastes and a penalty of €3mn for Chailley — lessened because he’d attempted to raise the alarm. They were the largest fines against an investment firm in the AMF’s history. Shockingly, the regulator was also pushing to ban Crastes from investment management for a decade.

“I’m an honest man. A simple man. Everything was done in the interest of investors,” Crastes told the committee. “It would be unjust to prevent me from doing the job I love.” Then he launched into an impassioned defence of his actions, his tanned hands underlining each point. “To be rational in an irrational market is not rational,” he explained. “The market is a representation of human beings. We are imperfect beings with emotions.”

When his turn came, Chailley struggled to maintain his composure. He glanced at the man who showed him how to navigate the world of finance, his partner and the older brother figure who increasingly ignored him as he grew closer to Windhorst. “We have been working together for 25 years,” Chailley said, voice quivering. “I am shocked.”

After the hearing, Crastes made his way up the basement stairs. Still reeling, he told an FT reporter: “I’m finished.”

Yet Crastes was not totally done.

When the regulator confirmed it was imposing a five-year fund management ban on Crastes in January 2023, H2O announced that its founder and chief executive would simply shift into a new role as its “corporate and market strategy director”. The same day, H2O announced its investors would finally get some money back after a repayment from Windhorst’s company. But it later emerged they would receive just €144mn, a fraction of the €1.6bn that had been frozen.

At the end of 2023, H2O wrote down the value of its remaining Windhorst investments and was hit with a lawsuit from thousands of aggrieved investors claiming they had lost hundreds of millions of euros. A company spokesperson told the FT: “H2O will continue to defend itself robustly in the appropriate forum against ill-founded allegations made against it and its employees, which it strongly denies.” H2O is currently appealing the AMF’s decision. Windhorst told the FT that his relationship with Crastes was in the “normal course of business” and “nothing inappropriate was ever done”.

Windhorst has spent much of the past year battling a fresh raft of lawsuits in London’s high court from creditors. During a day-long cross-examination in a sweltering courtroom last summer, he conceded under oath that it was “difficult” to say whether he was solvent. One of his largest creditors has yet to file suit against him, however: H2O Asset Management.

Cynthia O’Murchu is an FT investigative reporter. Robert Smith is an FT capital markets correspondent

© The Financial Times Limited 2024. All Rights Reserved.

FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times

Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.